What should be done to address the disparate patterns we find in student loan borrower outcomes? It goes without saying that curbing the rise in tuition costs and student loan debt borne by students and their families would address the problem at its root. In addition, reducing racial gaps in income and wealth would boost families’ ability to pay for tuition and repay student loan debt among segments of the population most burdened by student loan debt.

Setting aside these structural issues that contribute to the patterns of student loan repayment that we observe, below we explore a few possibilities for how targeted debt assistance programs could be expanded to alleviate the burden of existing student loan borrowers. As a general principle, because the majority of borrowers are managing their debt without being excessively burdened, efforts to alleviate undue burdens from student loan debt can and should be targeted at those who are experiencing truly difficult conditions. This is true for payment assistance efforts like income-driven repayment (IDR) programs as well as more aggressive actions like debt forgiveness.

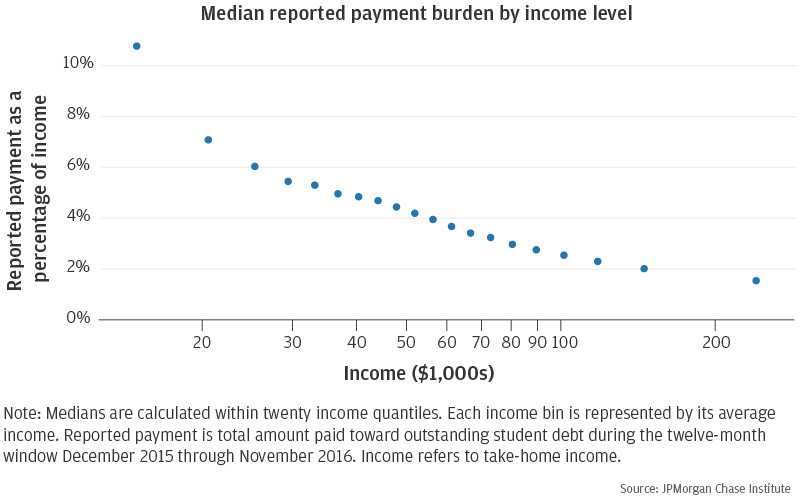

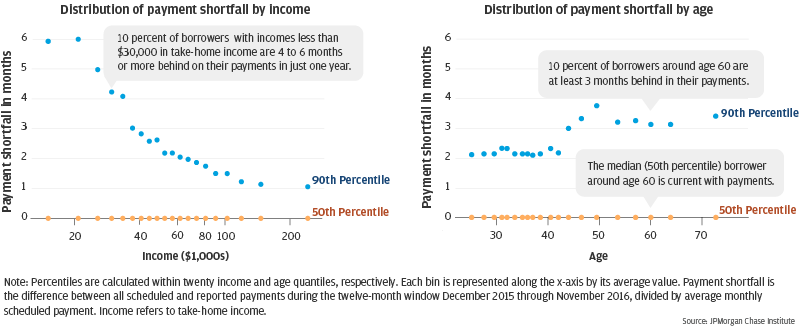

A relatively easy first step in expanding targeted assistance would be to help additional borrowers benefit from improved access to existing payment assistance programs, including income-driven repayment programs. One way to do this is to reduce the paperwork burden required to participate in IDR, such as making annual income recertification easier. Another is to increase efforts to make sure borrowers are aware of their IDR options. We observe that at least 10 percent of people are making payments that represent more than 10 percent of take-home income, a common threshold for IDR programs. We also observe high rates of deferment among low-income borrowers who might be eligible for IDR and eventual loan forgiveness.

However, it is important to note that current IDR programs do have drawbacks, and new programs may be warranted. IDR provides debt forgiveness only after twenty years of successful program participation. This extended time horizon makes debt forgiveness uncertain. Enrolling in an IDR program is also not without risk. If the borrower’s reduced payment is less than their monthly interest, the unpaid interest will continue to accumulate while the debt principal does not go down. Additionally, if the borrower leaves their IDR program, or fails to recertify their annual income on time, they will not only be responsible for all the unpaid interest but also for the unpaid interest that may be added to the debt principal and which can begin to accrue additional interest. This is a risk that has already been realized for many: in 2015, 57 percent of borrowers in IDR programs failed to recertify their income on time (Department of Education 2015).

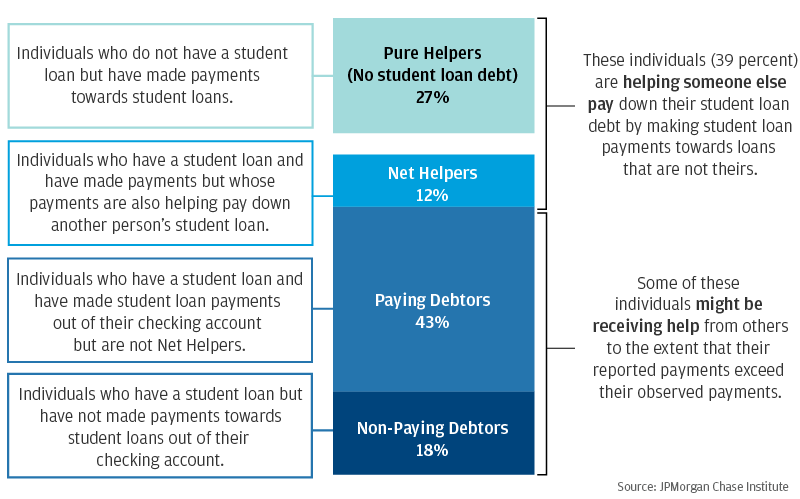

Our findings highlight that current student loan debt policies and assistance programs may not adequately consider the network of people the borrower may rely on to make their payments. This means that a borrower’s income statement may understate both her ability to pay and her vulnerability to job losses and financial disruptions among her financial support network. This issue has the potential to perpetuate intergenerational wealth inequalities and place undue burdens on parents. For wealthy parents, financing education through tuition or student loan repayment is a way to transfer wealth to the next generation. For less wealthy parents, student loan debt repayment is an added financial burden to face if they do not benefit from their children’s income premium.

Student loan policies should take these family dynamics into account. First, loan origination programs may need to rebalance eligibility of loans between students and parents. Loan origination programs currently make a clear distinction between borrowers and their parents. For example, federal Parent PLUS loans, which are taken out by parents of dependent undergraduates on behalf of their children, have higher interest rates and limits than those provided directly to undergraduate students. We observe younger borrowers making payments on loans that are not in their name and older borrowers receiving help with their loans, most of which are Parent PLUS loans. This suggests that many students are repaying their parents’ loans. What are the redistributive implications if these loans are ultimately paid by the students themselves? Should loan limits be increased in order to enable students to officially take on more of the debt, giving them access to lower interest rates and current payment assistance programs?

Second, perhaps there should be more avenues for payment assistance designed for parents. Borrowers on instruments like Parent PLUS loans are not eligible for programs like IDR. This creates a potential pitfall for parents who borrow on behalf of their children. If the student completes college and earns an income premium, they can help their parents with parent-borne loans. Our observations of the large amount of help received by senior borrowers suggests this may be a common practice. However, if the student cannot sufficiently earn a premium, they have access to some assistance, like IDR, but probably won’t be able to help their parents who do not have any avenue for assistance. And with a meaningful share of older Americans involved in student loan repayment making progress at a very slow rate, their debt burdens may very well stretch into retirement.

A possible complement to repayment relief programs is to allow for restructuring or forgiveness of student debt through a bankruptcy-like process. Currently, student debt is only dischargeable under Chapter 13 (debt restructuring) when a debtor can convince a judge that they have extreme economic hardship and if the debtor completes a rigorous five-year repayment program. In practice, this happens very rarely. Enabling student debt to be discharged might ultimately increase the cost of borrowing to the extent that the existence of the policy changes default rates. Targeting discharge—for example to those with limited assets and have been in default for several years—could mitigate these price effects.

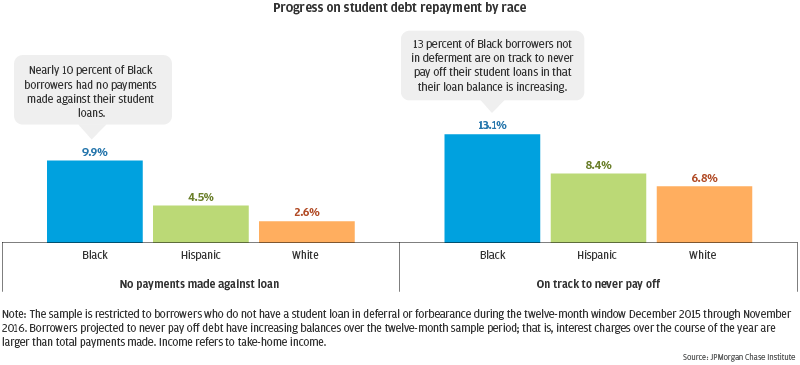

A further step to address undue payment burdens would be to expand efforts to provide targeted debt forgiveness to those most burdened. Although debt relief is available for graduates entering certain careers and for those who remain in an IDR program for twenty years, our evidence suggests there is an opportunity to expand avenues for targeted debt relief. We find that a higher share of lower-income and Black borrowers face extreme payment burdens (over 10 percent of take-home income) and are projected to never finish paying off their loans if current repayment trends continue. Given the disproportionate structural challenges Black and Hispanic families face within the labor market, there is strong evidence of racial gaps in income (Farrell et al. 2020). Thus, returns to education could be lower for Black and Hispanic graduates than White graduates, making it mechanically more challenging for Black and Hispanic borrowers to effectively repay their student loans. Targeted student loan debt forgiveness could be a means of rebalancing our investments in public goods like education across communities and insuring against the risk that borrowers, Black and Hispanic borrowers disproportionately, find themselves in a debt trap.