Figure 1: During the pandemic, a larger share of necessity entrepreneurs was female.

Research

October 29, 2024

The gender gap in financial health is well-documented, with women generally having fewer financial resources than men. This gap is partially attributed to lower labor income earned by women and cannot be fully explained by job characteristics (Ruel and Hauser 2013; Blau and Kahn 2007). Consequently, some women might opt for self-employment instead of wage employment.

However, the gender gap is also evident among small businesses: female-owned firms have consistently earned lower revenues than businesses owned by men. A frequently cited potential driver of these revenue differences is that women and men start businesses in different industries, but the gender revenue gap occurred in nearly every industry, suggesting that lower revenues among female-owned firms was not entirely driven by disproportionate shares of women founding businesses in low-revenue industries (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2019).

An alternative explanation for the gender revenue gap is that women start businesses for different reasons and in the context of different economic circumstances. The motives of entrepreneurs and the economic conditions in which they start their firms may affect not only the types of businesses they found but also their outcomes. In recent research, we demonstrated that entrepreneurs who started businesses out of necessity—after involuntary unemployment—founded firms that were smaller and more likely to exit in the initial years (Wheat and Mac 2024). In this companion report, we investigated the role of necessity entrepreneurship among women and the implications for the types of businesses they start. Our results suggest that necessity entrepreneurship among women does little to explain the persistent gender revenue gap. This result suggests that policies that target motivations alone may also have a limited impact on closing the gap.

We analyzed firms of both necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs started in different economic conditions over 14 years, a period that includes two recessions. Our unique data asset provides the basis for our distinct contribution in not only identifying necessity entrepreneurs but also studying their financial outcomes. In particular, we found:

Data asset and methodology

Our research sample consisted of over 880,000 de-identified firms with Chase Business Banking deposit accounts that meet our criteria for being active and small in the first 12 months after the account opened. In addition, all firms in our sample had at least one owner with a Chase personal deposit account in the year prior to opening the business account. If there was evidence of unemployment insurance payments in the personal account during that period, the firm was classified as having been founded by a necessity entrepreneur. All other firms were considered to be started by opportunity entrepreneurs. See our related report for more details on sample construction (Wheat and Mac 2024).

Lower revenues among female-owned firms relative to male-owned ones might be partially explained if women were more likely to be necessity entrepreneurs, who typically start businesses with lower revenues than opportunity entrepreneurs. In our sample of firms started between 2009 and 2022, there was little difference between female and male necessity entrepreneurship except during the pandemic.

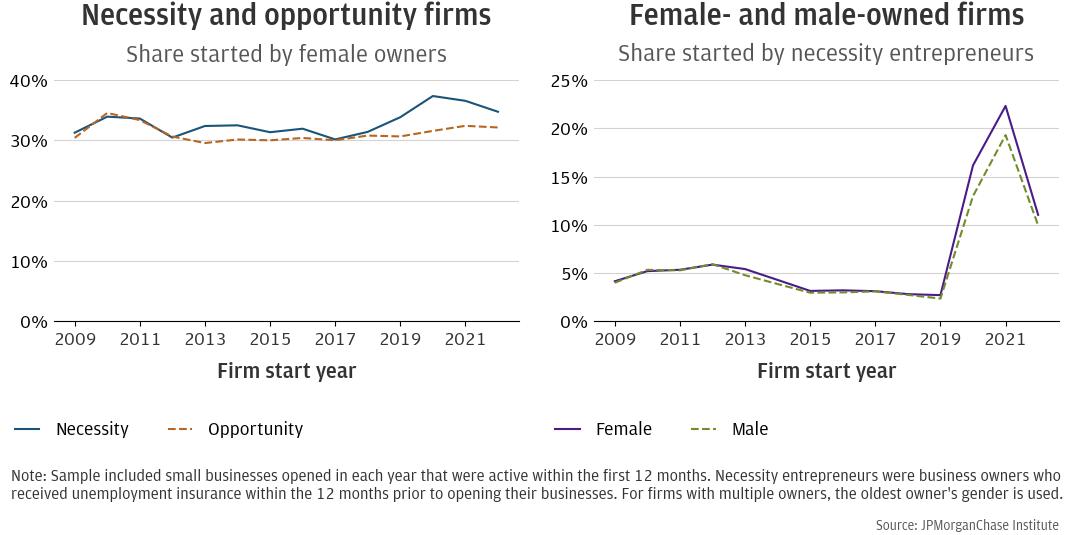

Figure 1 considers the gender distribution of necessity and opportunities in two ways. The left panel shows the share of necessity and opportunity firms started each year that were started by women. Women founded about 30 percent of opportunity firms and about the same share of necessity firms.1 During the pandemic, the share of necessity firms started by women was slightly higher. Altogether, this suggests that necessity firms are not disproportionately female-owned.

The right panel of Figure 1 shows the shares of female- and male-owned firms each year that were founded by necessity entrepreneurs. The shares were similar across businesses founded by women and men, with slightly higher rates of necessity entrepreneurship for women during the pandemic. Nevertheless, the shares were similar across most cohorts, indicating that women are generally not more likely to be necessity entrepreneurs.

Our results do not support a hypothesis that female-owned firms earn lower revenues because they are disproportionately founded by necessity entrepreneurs. However, our identification of necessity entrepreneurs relies on the receipt of unemployment insurance in the year prior to starting the business. While this criterion can be applied objectively across a large sample, it may miss other types of necessity entrepreneurship or circumstances that may not fit exclusively into concepts of “necessity” or “opportunity.” For example, some may leave the labor force voluntarily and choose between wage employment and self-employment when they reenter. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, employment and labor force participation rates decreased, and the decline was particularly marked among women and mothers (Alon et al. 2020; Bauer 2021). The labor force participation for women aged 25 to 54 has since rebounded (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2023). Gains have been attributed to the availability of telework (Terrazas 2023), but another option for participating in the labor force is self-employment.

Entrepreneurship is not as common as wage employment, but it is nevertheless an alternative that over 10 percent of the labor force chooses.2 Entrepreneurs may start businesses for many reasons. In a survey of new business owners, the majority—62 percent of men and 64 percent of women—cited flexibility as one reason for starting a business, but men were more likely to cite seizing a business opportunity as another reason compared to women (44 percent compared to 32 percent, respectively) (Pardue 2023). Our results suggest that women are not generally more likely to be necessity entrepreneurs, but that does not necessarily mean that entrepreneurs who did not experience involuntary unemployment were taking advantage of business opportunities.

In prior research, we documented the lower revenues of businesses founded by women relative to ones founded by men, and that gap did not diminish over the first four years of operations (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2019). In recent work, we found that firms started by necessity entrepreneurs were smaller than those founded by opportunity entrepreneurs, and that relationship held at different parts of the business cycle and after controlling for firm characteristics, such as industry (Wheat and Mac 2024). Although women are not generally overrepresented among necessity entrepreneurs, perhaps the gender revenue gap is diminished among women and men who started firms under similar circumstances.

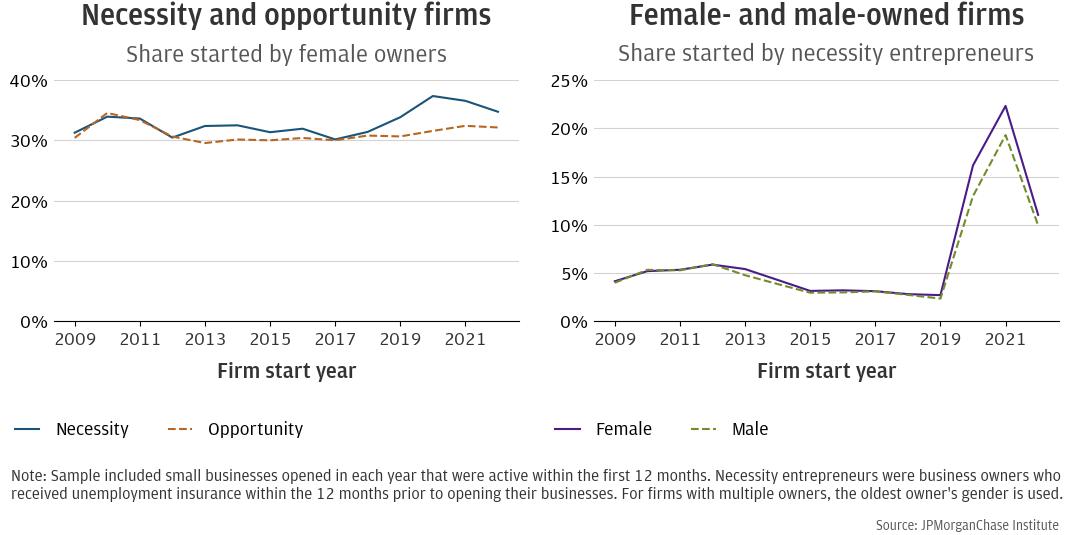

Figure 2 shows that the gender revenue gap persists even among firms started by necessity or opportunity entrepreneurs. Among the necessity entrepreneurs shown on the right panel, female necessity entrepreneurs started firms that earned lower revenues than ones founded by their male counterparts despite similar experiences with involuntary unemployment. However, the gender revenue gap for necessity firms was smaller than the gap among opportunity firms in some years, particularly for firms founded around the Great Recession. Among opportunity entrepreneurs, the revenue gap was relatively consistent over time.

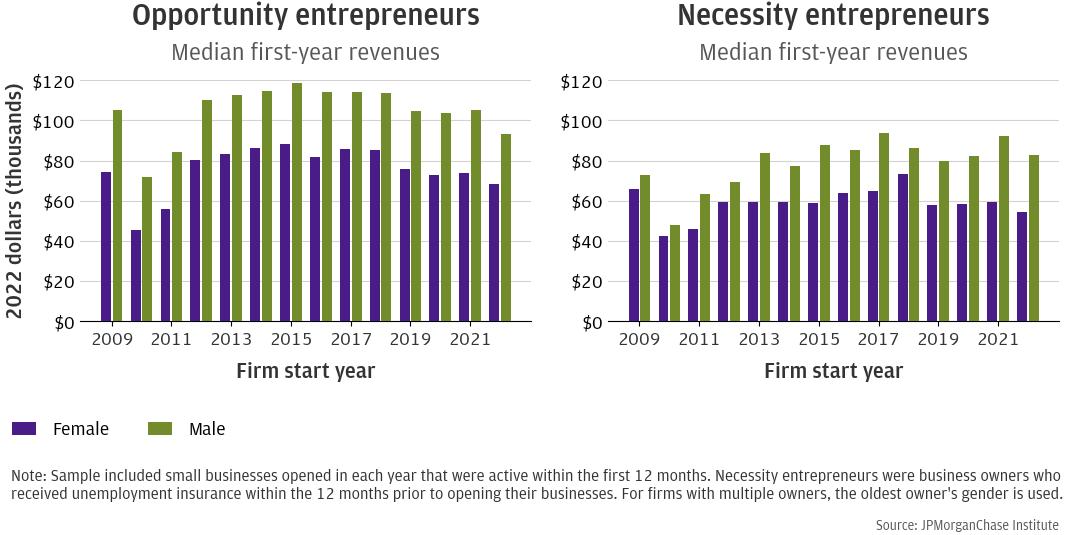

Some of the difference may be attributed to the different types of firms that men and women start. For example, female-owned firms are overrepresented in personal services (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2019), an industry with lower typical revenues. Using a regression model, we estimated the first-year revenues of male and female entrepreneurs while holding firm characteristics constant.3 Figure 3 shows that even after accounting for observable firm characteristics, firms started by female necessity entrepreneurs were smaller than ones founded by their male counterparts. A similar gap persisted among opportunity entrepreneurs.

These estimates suggest that neither recent involuntary unemployment nor observable firm characteristics fully account for the gender revenue gap. However, the somewhat smaller estimated difference among necessity entrepreneurs also suggests that the circumstances under which businesses are founded are relevant factors in firm size. In our analysis, necessity entrepreneurship included one circumstance—starting a business within 12 months of receiving unemployment insurance. Women could potentially be overrepresented in other types of necessity entrepreneurship that are not captured by our focus on involuntary unemployment.

Although smaller firms typically exit at higher rates, prior research found that female-owned firms exited at similar rates as male-owned ones (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2020). That pattern is also evident among necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs.

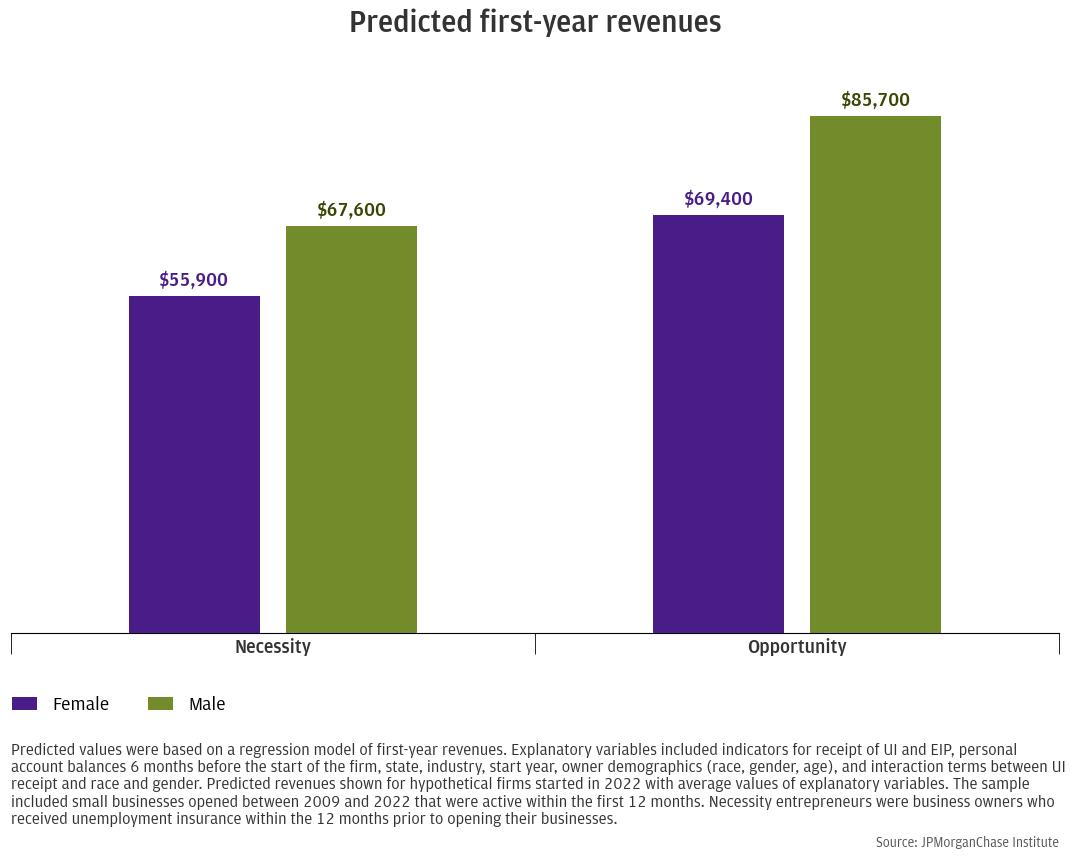

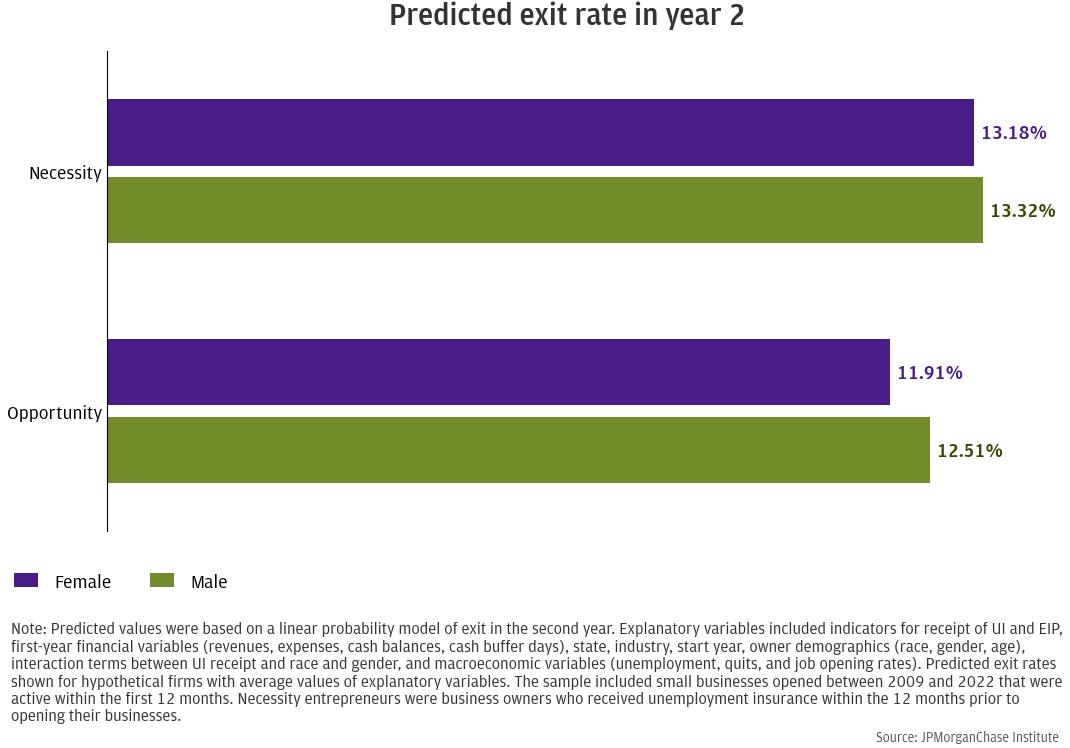

Figure 4 shows the estimated probabilities of exit for necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs. Using a regression model to hold firm characteristics such as industry and state constant, as well as macroeconomic variables such as the unemployment rate, we calculated the predicted exit rates in the second year.4 Necessity entrepreneurs were more likely to exit than opportunity entrepreneurs, but male and female necessity entrepreneurs were estimated to exit at similar rates.

Necessity entrepreneurs in our sample were previously engaged in wage employment, so it is perhaps unsurprising that even after controlling for observable variables, they may prefer to return to wage employment when possible. Female opportunity entrepreneurs were predicted to exit at slightly lower rates than males after controlling for firm and macroeconomic variables. Overall, our results suggest that firms founded by women are at least as likely to survive as ones started by men.

Firms started by necessity entrepreneurs are typically smaller and more likely to exit in the initial years compared to those started by opportunity entrepreneurs. During economic downturns, a larger share of new businesses is founded by necessity entrepreneurs. However, necessity entrepreneurs were generally not more likely to be women, although there were slightly more female necessity entrepreneurs during the pandemic.

This implies that female necessity entrepreneurship cannot explain the gender revenue gap. However, there may be circumstances other than involuntary unemployment that may affect the types of businesses women and men tend to start. For example, caregiving responsibilities, which often fall more heavily on women, may be a factor in the industries they choose or the number of hours they devote.

Self-employment may be viable options for some workers, based on skills, preferences, and labor market conditions. Transitions between self-employment and wage employment can be part of a healthy economy, labor market, and business dynamism. Policies such as affordable health, child, and elder care could allow workers to choose entrepreneurship to pursue business growth opportunities instead of doing so out of necessity, which in turn could lead to more economic growth.

Alon, Titan, Matthias Doepke, Jane Olmstead-Rumsey, and Michèle Tertilt. 2020. “This Time It’s Different: The Role of Women’s Employment in a Pandemic Recession.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 27660. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27660/w27660.pdf.

Bauer, Lauren. 2021. “Mothers are Being Left Behind in the Economic Recovery from COVID-19.” The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/post/mothers-are-being-left-behind-in-the-economic-recovery-from-covid-19/.

Blau, Francine D. and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2007. “The Gender Pay Gap: Have Women Gone as Far as They Can?” Academy of Management Perspectives, 21(1), 7-23.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 2023. “Labor force participation rate for people ages 25 to 54 in May 2023 highest since January 2007.” The Economics Daily. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2023/labor-force-participation-rate-for-people-ages-25-to-54-in-may-2023-highest-since-january-2007.htm.

Ewing Maron Kauffman Foundation. 2022. “Who is the Entrepreneur? New Entrepreneurs in the United States, 1996-2021.” Trends in Entrepreneurship. Kansas City, Missouri.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2019. “Gender, Age, and Small Business Financial Outcomes.” JPMorganChase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/institute/pdf/institute-report-small-business-financial-outcomes.pdf.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2020. “Small Business Owner Race, Liquidity, and Survival.” JPMorganChase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/all-topics/business-growth-and-entrepreneurship/report-small-business-owner-race-liquidity-survival.

Gregory, Victoria, Elisabeth Harding, and Joel Steinberg. 2022. “Self-Employment Grows during COVID-19 Pandemic.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2022/jul/self-employment-returns-growth-path-pandemic.

Pardue, Luke. 2023. “Survey: Inflation Driving New Business Creation in 2022 As Entrepreneurship Continues to Surge.” Gusto.

Ruel, Erin and Robert M. Hauser. 2013. “Explaining the Gender Wealth Gap.” Demography, 50(4), 1155-1176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0182-0.

Terrazas, Aaron. 2023. “April Jobs Report Preview: Spring Hopes Eternal.” Glassdoor. https://www.glassdoor.com/research/jobs-report-preview-april-2023.

Wheat, Chris and Chi Mac. 2024. “When opportunity knocks: How economic cycles shape entrepreneurial ventures and their success.” JPMorganChase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/all-topics/business-growth-and-entrepreneurship/when-opportunity-knocks-how-economic-cycles-shape-entrepreneurial-ventures-and-their-success

We thank Karmen Hutchinson and Man Xu for their hard work and vital contributions to this research. Additionally, we thank Oscar Cruz, Annabel Jouard, and Alfonso Zenteno for their support. We are indebted to our internal partners and colleagues, who support delivery of our agenda in a myriad of ways and acknowledge their contributions to each and all releases.

We would like to acknowledge Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., for his vision and leadership in establishing the Institute and enabling the ongoing research agenda. We remain deeply grateful to Peter Scher, Vice Chairman; Tim Berry, Head of Corporate Responsibility; Heather Higginbottom, Head of Research, Policy, and Insights and others across the firm for the resources and support to pioneer a new approach to contribute to global economic analysis and insight.

This material is a product of JPMorganChase Institute and is provided to you solely for general information purposes. Unless otherwise specifically stated, any views or opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors listed and may differ from the views and opinions expressed by J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS) Research Department or other departments or divisions of JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates. This material is not a product of the Research Department of JPMS. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively J.P. Morgan) do not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. No representation or warranty should be made with regard to any computations, graphs, tables, diagrams or commentary in this material, which is provided for illustration/reference purposes only. The data relied on for this report are based on past transactions and may not be indicative of future results. J.P. Morgan assumes no duty to update any information in this material in the event that such information changes. The opinion herein should not be construed as an individual recommendation for any particular client and is not intended as advice or recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, or strategies for a particular client. This material does not constitute a solicitation or offer in any jurisdiction where such a solicitation is unlawful.

Wheat, Chris and Chi Mac. 2024. “Does necessity entrepreneurship explain the gender revenue gap?” JPMorganChase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/all-topics/business-growth-and-entrepreneurship/does-necessity-entrepreneurship-explain-the-gender-revenue-gap.

Footnotes

These shares of female-owned firms are lower than other benchmarks. For example, the Kauffman Foundation documented that about 40 percent of new entrepreneurs are women (2022).

Based on the Current Population Survey, over 10 percent of the U.S. labor force was self-employed in 2022 (Gregory, Harding, and Steinberg 2022).

See Wheat and Mac (2024) for details on the regression model.

See Wheat and Mac (2024) for details on the linear probability model.

Authors

Chris Wheat

President, JPMorganChase Institute

Chi Mac

Business Research Director