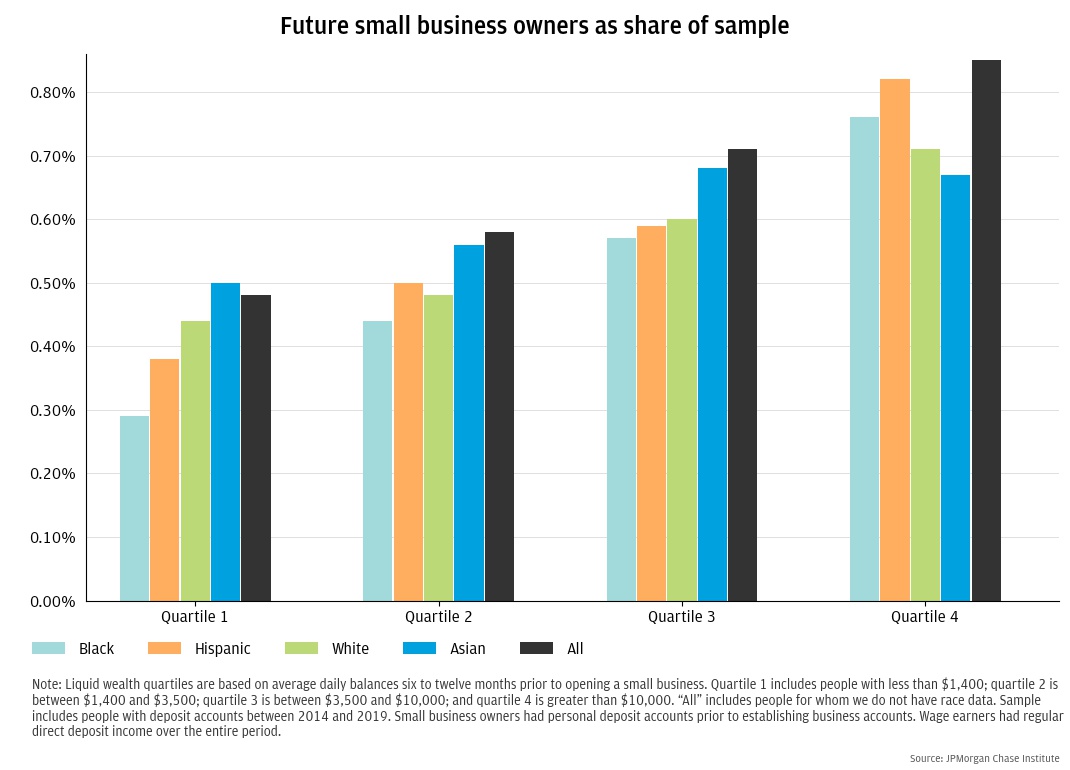

Table 1: Demographic comparison of future small business owners and wage earners

Findings

The relationship between small business ownership and wealth looms large in the imagination of policymakers and entrepreneurs alike. Indeed, people who own businesses are wealthier than those who do not. In 2019, the median net worth of self-employed families was $380,000—over four times larger than the $90,000 in net worth held by the typical working family (Headd 2021). Perhaps for this reason, thousands of people every year decide to start a business, though a similar number of businesses exit each year as well. A key question for policymakers is the extent to which business ownership itself is responsible for this difference in wealth.

To date, most studies have found that small business ownership is concentrated among higher-wealth people prior to starting a business (Evans and Jovanovic 1989; Fairlie and Krashinsky 2012) although some research has found that, after removing the wealthiest entrepreneurs, this might not be true (Hurst and Lusardi 2004). Using de-identified Chase personal and small business deposit account data we explored cash balances for small business owners prior to starting a small business, over the first two years of operation, and around the time of a firm’s exit. This allowed us to understand the liquid wealth of small business owners when making important financial decisions at critical moments.

In this brief we studied the liquid wealth of small business owners as they start new firms, and as they close firms. To do this, we leveraged a unique data set that offers a granular, longitudinal, and high-frequency lens on financial outcomes, both for people and the businesses they own. Importantly, it provides a perspective on the financial health of small business owners before they open their businesses. Our lens on liquid wealth is the average daily balance across all savings and checking accounts held by a person or small business in our study period. It does not include assets contributing to total wealth like brokerage accounts or physical property. While our focus on liquid wealth structurally understates the total wealth available to people, it provides an unprecedented lens on the evolution of small business owner finances through the entrepreneurial life cycle. Moreover, if people with more wealth generally hold more cash than those with less wealth, then liquid wealth can still provide a view of relative wealth.

Our findings are threefold. First, we find that the typical small business owner had higher liquid wealth than wage earners prior to starting a small business. Second, among small business owners, differences in liquid wealth may impact a small business’s ability to grow and, therefore, generate wealth for the owner. Third, small business owners who close their firms tend to have lower liquid wealth than owners whose businesses stay open.

We selected our samples from 3.7 million de-identified people who actively used Chase banking products between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2019, consisting of 320,000 people identified as small business owners and the remaining people who we identified as wage earners. Our study period ends prior to 2020 because of the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the federal government’s response. Federal relief programs contributed to elevated small business (Wheat and Mac 2021) and personal (Greig, Deadman, and Sonthalia 2021) balances. Limiting our study period to only cover outcomes through 2019 allowed us to understand typical liquid wealth without COVID-19 related support.

We used a three-step process to identify wage earners and small business owners. We first identified the universe of people who we believe used Chase as their primary bank, then identified the universe of small businesses that we believe actively used Chase as their primary bank, and then identified small business owners and wage earners from our universe of people. We identified small business owners in this sample as people who had sufficient activity in Chase personal accounts and were also listed as owners on a business account. We identified wage earners as people who were not small business owners and met a minimum threshold of direct deposit transactions in every year of our sample. Although many wage earners do not receive direct deposit paychecks, this restriction allowed us to better identify wage earners who were less likely to be small business owners of firms banked elsewhere.

Our direct deposit requirement likely made our sample of wage earners different from the general population. Specifically, these people were regularly employed and had a stable relationship with a bank. This could mean that our sample had higher levels of liquid wealth than the general population, and that we might overstate the liquid wealth of people who do not own small businesses. If true, our findings understate the true difference in liquid wealth between wage earners and small business owners.

We identify race and gender through modeled data provided by a third-party vendor.1

The observation that small business owners are often wealthier than wage earners does not imply that starting or otherwise taking on the ownership of a small business leads to wealth growth. As a first step in clarifying this relationship, we compared the liquid wealth of a sample of people who would later start small businesses to a population of wage earners. We found that these future small business owners were wealthier than their wage-earning counterparts before they started their small businesses.

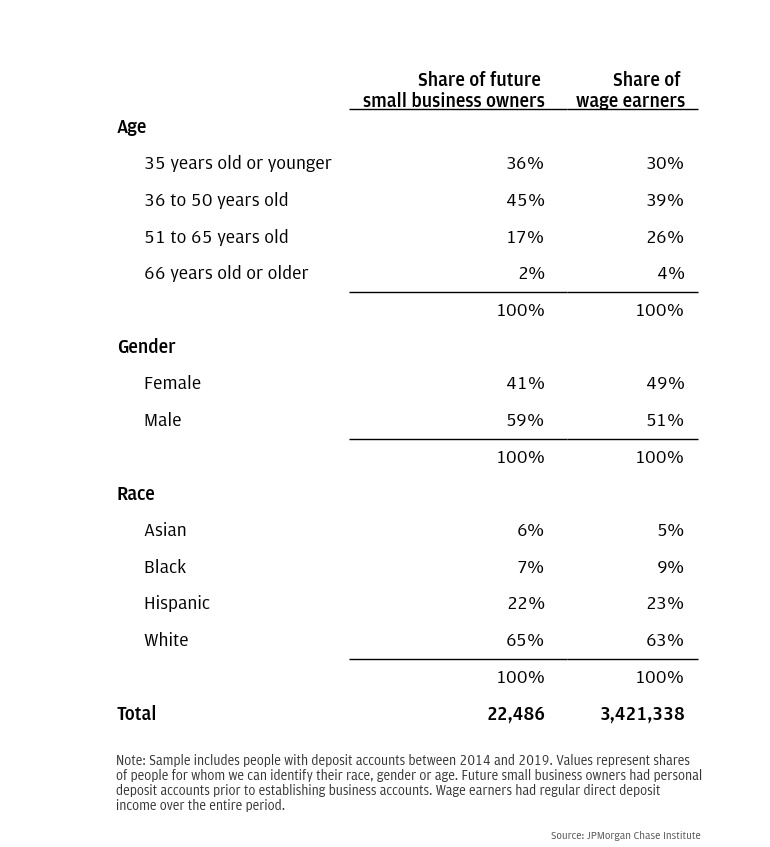

From our full sample, we identified 22,500 people who started small businesses in the three years from 2015 through 2017, were the sole owner of their businesses, and who had at least 36 months of personal banking activity.2 These 36 months correspond to 12 months of personal banking activity prior to starting a business and 24 months of personal and business banking activity after the business starts. Table 1 compares the demographics of this group of future small business owners and a group of wage earners during this time.

Table 1: Demographic comparison of future small business owners and wage earners

Future small business owners in our sample were younger than wage earners, and, notably, more likely to be under 35. This characteristic of our sample is especially notable given the observation that self-employed workers are generally older than non-self-employed workers (Christnacht, Smith, and Chenevert 2018). Additionally, small business owners were less likely to be female.3

Among those people for whom we could identify race, our sample of future small business owners was similar to our sample of wage earners. That is, about two-thirds were White, about 20 percent were Hispanic, and less than 10 percent were Asian or Black, respectively.

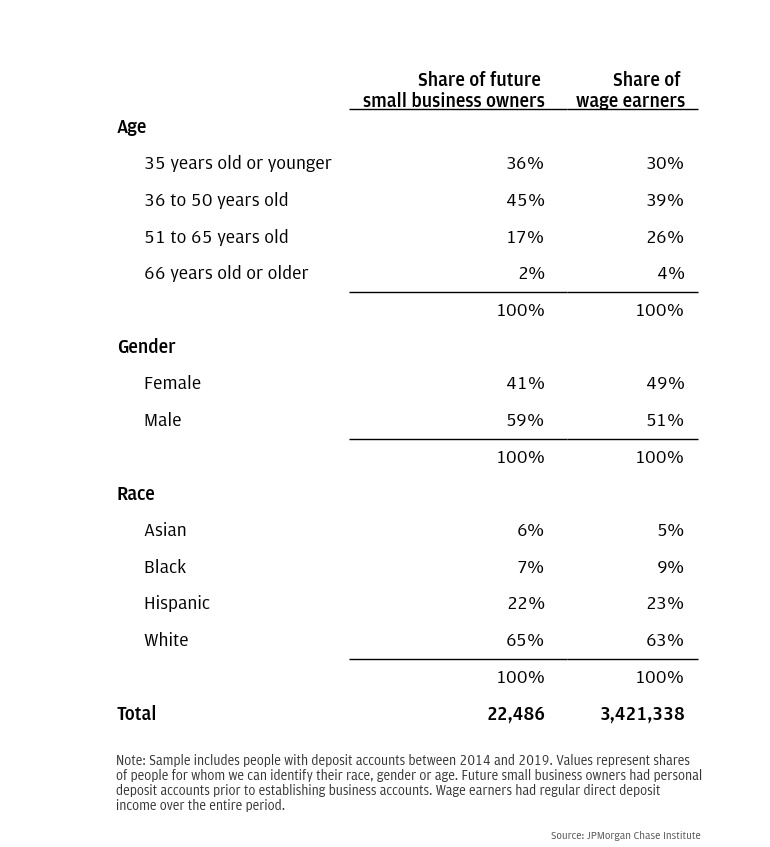

We calculated liquid wealth by finding the average daily cash balances people held six to twelve months prior to starting a small business.4 To compare the liquid wealth of future business owners to wage earners, we evaluated wage earner average daily cash balances over a random period for seven consecutive months between 2014 and 2016, which corresponded to the allowable pre-business period for firms that started between 2015 and 2017. We found that in the period prior to starting a firm, the typical future small business owner had more liquid wealth than the typical wage earner. This suggests that a meaningful share of any differences in wealth between people who own businesses and those who do not is attributable to wealth differences that existed prior to firm ownership.

Figure 1 shows that the typical future small business owner had about 40 percent more liquid wealth than the typical wage earner. This large difference suggests that future small business owners may require some level of wealth either to mitigate the risk of entrepreneurship or to invest in the new business. If a minimum level of liquid wealth is required to comfortably start a small business, then this could be a barrier of entry for some entrepreneurial wage earners.

Our estimates may understate the difference in liquid wealth between future small business owners and the general population. Our comparison group of wage earners has consistent income through direct deposits and is somewhat older than the future small business owners. Older Americans generally have more liquid wealth than younger Americans, which suggests that our sample of wage earners may have more liquid wealth than the broader universe of wage earners (Greig, Deadman, and Noel 2021).

Figure 1: Future small business owners had higher liquid wealth than wage earners

Previous research has shown that Black and Hispanic Americans generally have lower overall wealth and liquid wealth than their White peers (McIntosh et al. 2020, Farrell et al. 2020), and this seems to be true of small business owners as well. Although the median Black future small business owner was wealthier than the median Black wage earner, the median Black founder had less wealth than either the median White wage earner or future small business owner. This was also true for Hispanic small business owners. This suggests that the racial wealth gap exists among future small business owners as well as wage earners, and it persists even among small business owners whose firms survive the first four years (Wheat, Mac, and Tremper 2021). This gap in resources should be addressed if entrepreneurship is to be a lever in decreasing the overall racial wealth gap.

There was also significant difference in the liquid wealth levels between the typical wage earner and typical founder of the same race. The typical White founder entered small business ownership with 30 percent more liquid wealth than the typical wage earner, but the typical Black and Hispanic founder entered with 70 percent and 50 percent more liquid wealth than the respective wage earner. This larger difference may be due to the low levels of liquid wealth for the typical Black and Hispanic wage earner. This suggests that, even if desired, the transition from wage earner to small business owner might be more difficult for Black and Hispanic wage earners because of limited initial wealth.

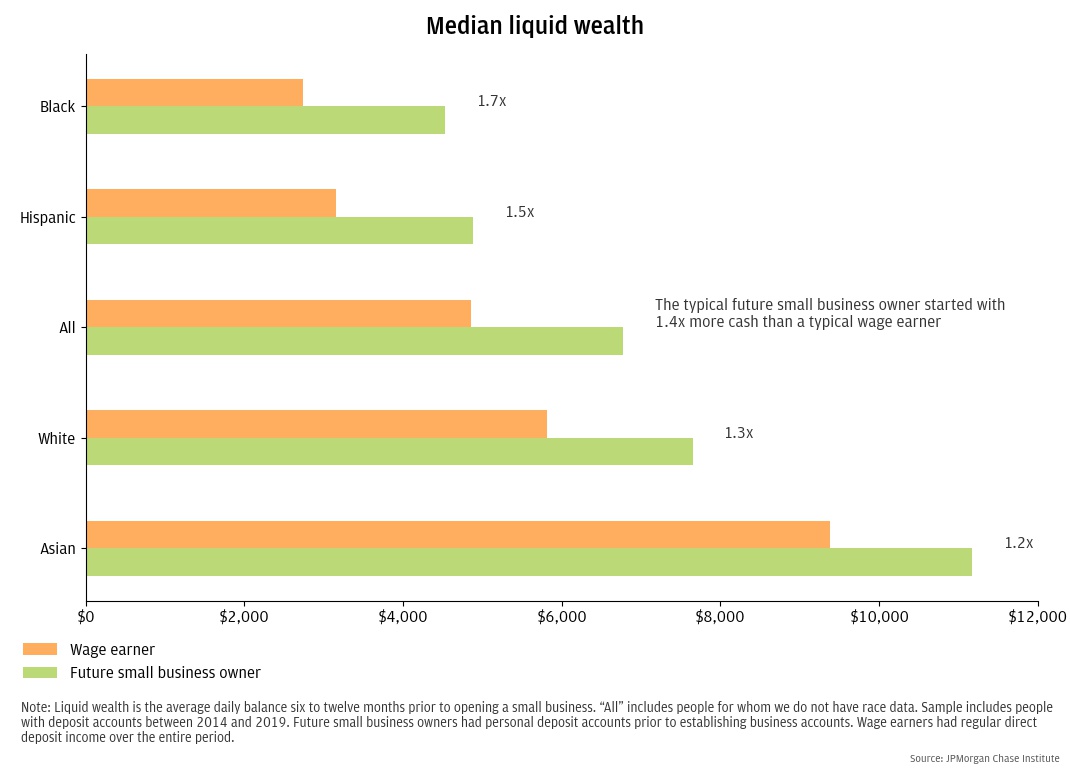

People who are more likely to start a small business tend to have higher levels of liquid wealth. Figure 2 shows the share of people in each race starting a business by liquid wealth quartile. The liquid wealth quartiles were based on the combined sample of future small business owners and wage earners. Those in the first quartile had an average daily balance of less than $1,400, those in the second quartile had average daily balances between $1,400 and $3,500, people in the third quartile had balances between $3,500 and $10,000, and people in the fourth quartile had average daily balances greater than $10,000. About 0.9 percent of people in the fourth quartile started a small business in the three years from 2015 through 2017, while only 0.5 percent of people in the first quartile did so.5 That is, someone in the fourth quartile was almost twice as likely to start a small business in these three years as someone in the first quartile.

Figure 2 also shows that about 0.75 percent of both Black and White people in the top quartile of liquid wealth started businesses. Regardless of race, people in the fourth quartile were similarly likely to start a business. However, future small business owners in the fourth quartile were more likely to be White: 70 percent of owners for whom we could identify race in the top quartile were White compared to 65 percent in future small business owners overall. Less than 5 percent in this quartile were Black, compared to 7 percent overall. Moreover, these racial gaps in small business ownership were more pronounced among people with less liquid wealth. Black people in the first quartile of liquid wealth were approximately one-third less likely to start businesses than their White counterparts.

Figure 2: Larger shares of high-wealth people start small businesses

People who become small business owners take on some level of financial risk. Therefore, aspiring founders might believe that a comfortable amount of cash is required before they embark upon business ownership. These considerations are consistent with our finding: small business owners were wealthier than wage earners prior to founding their firms, and wealthier people are more likely to start small businesses. Existing racial wealth inequities can filter through, potentially affecting the viability of small business ownership as a lever for reducing the racial wealth gap.

The typical firm owner entered business ownership with much more liquid wealth than the typical wage earner. However, even among small business owners, wealth levels were not uniformly high, which can affect the resources available to invest in the business.

Business owner liquid wealth is difficult to characterize, even among businesses with single owners. They may hold cash in both their personal and business deposit accounts, and transfer funds easily between the two in ways that may or may not relate to the operational performance of the business. Notably, about 75 percent of all small business owners invest their own funds to start their business (U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy 2022), reinforcing the idea that firm balances, especially in the early days of a small business, overlap substantially with a founder’s personal cash balances. Given this fluidity, we explored both personal cash balances and combined personal and firm balances as indicators of business owner wealth.

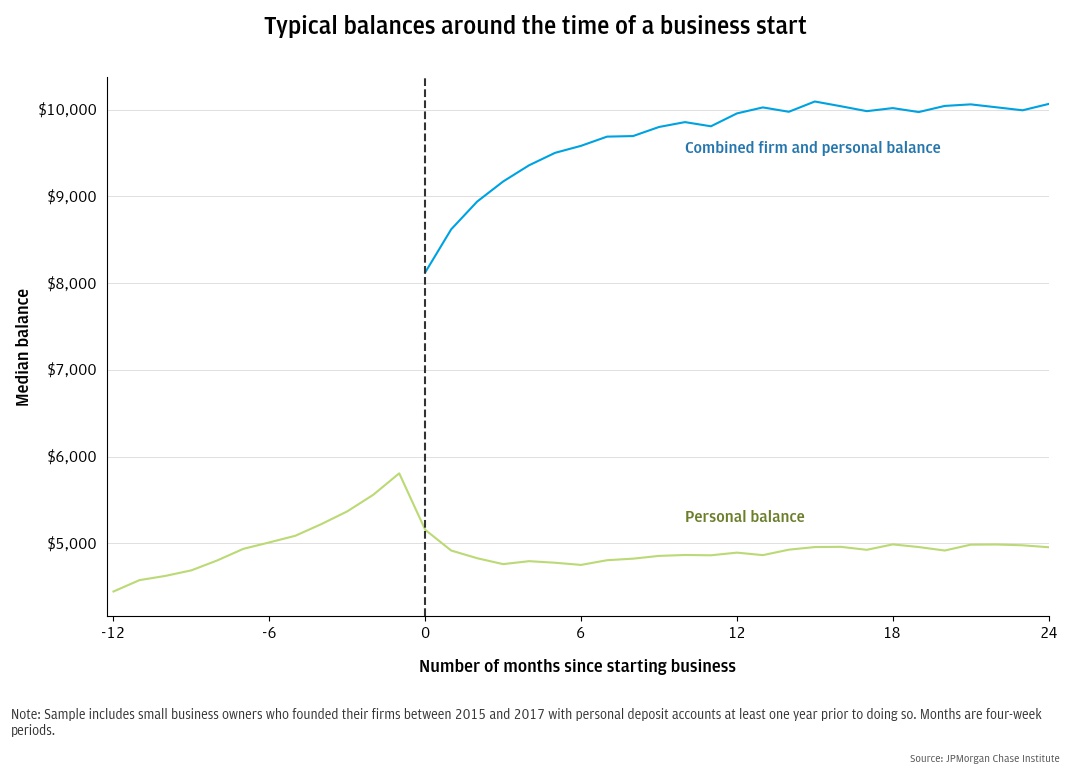

Figure 3 shows the median small business owner’s liquid wealth over the 36 months around a firm’s start. It includes the typical personal balances 12 months prior to and continuing through the first 24 months after starting a business. Figure 3 also shows the median owner’s combined liquid wealth as the sum of firm and personal balances for 24 months after starting a business.

The typical small business owner increased their personal balances in advance of starting a business, and then experienced an increase in combined liquid wealth in the month that the business opens. The increase in combined wealth in the month of firm opening exceeded the decline in personal wealth observed in the same month. This suggests that the firm’s initial balances were not entirely comprised of personal funds. Early firm balances can be an aggregate of both operating and financial flows. Operating flows include revenues and expenses, but financial flows could be transfers from the owner, the owner’s family and friends, or traditional bank loans or other outside investments.

The decrease in the typical firm owner’s personal balances was steep but not long lasting. This is consistent with a small business owner building savings to, at least partly, fund the business with her own wealth. Within a couple months of a business opening, the combined liquid wealth of the typical business owner began to stabilize, perhaps suggesting that operating flows overtook financial flows as the primary driver of balance changes. Additionally, personal balances generally remained at pre-business levels.

Figure 3: Personal balances increase before and decrease after business founding

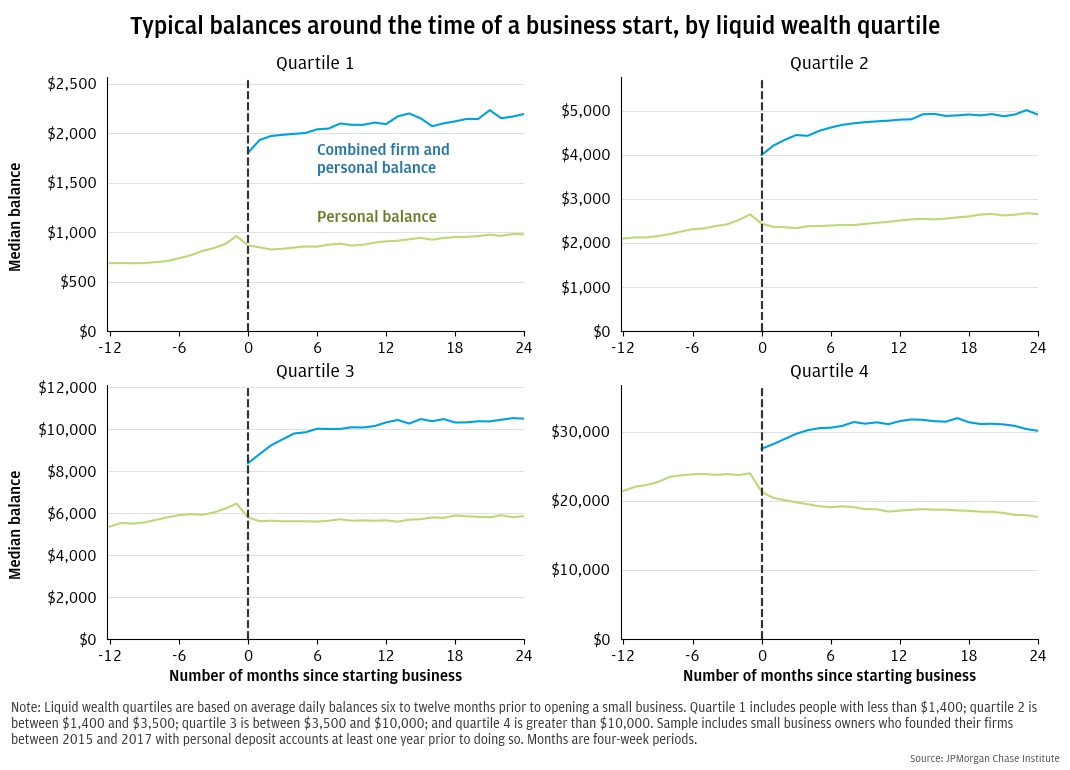

As Finding 1 showed, people who start small businesses typically had more liquid wealth than wage earners, but not all people who started businesses had substantial wealth. To understand how cash balances changed for people across the liquid wealth distribution we analyzed small business owners in each quartile of liquid wealth among our entire sample (small busines owners and wage earners). Differences in small business owner liquid wealth may have implications on how small business owners operate their new firms.

The months immediately following a small business start were varied for people with different levels of liquid wealth prior to entering entrepreneurship. Figure 4 shows the trajectories of personal and combined liquid wealth of small business owners in the 36 months around starting a business, by the quartile of owner liquid wealth prior to business start. Regardless of initial wealth, the typical small business owner experienced modest changes in combined liquid wealth during the first two years.

Figure 4: Small business owners with more personal wealth are able to invest more in their businesses

Nearly 20 percent of small business owners were in the lowest liquid wealth quartile among our whole sample, and 33 percent of were in the highest quartile. The typical founder in the first quartile had about $1,000 in liquid wealth the month prior to starting a business, whereas the typical founder in the fourth quartile had about $24,000 in liquid wealth the month before starting a business.

The typical small business owner in the first quartile had very low liquid wealth prior to starting a business, and the typical personal balance decreased very little when the firm opened. Limited liquid wealth might have made it difficult to provide initial investment for a business. Most small business financing comes from the owner’s personal funds (U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy 2022), and sufficient financing is highly correlated with higher revenues, a key piece of small business growth (Gartner, Frid, and Alexander 2012). People who start their small businesses with lower levels of liquid wealth may be less able to finance their business and benefit from higher revenues and potential business growth. This could limit their ability to generate wealth as their business matures.

On the other end of the spectrum, the typical small business owner in the fourth quartile had high personal liquid wealth prior to starting a firm, with balances decreasing significantly when the new firm opened. In the subsequent two years, the typical high wealth small business owner drew down personal balances as combined liquid wealth increased and then remained relatively steady. This owner might have been able to use her own personal wealth to provide liquidity for a business that was not immediately profitable or to forgo extracting profits in favor of reinvesting in the business. In either case, this small business owner seems to have invested in this business, which could give it a better chance to grow and, therefore, generate wealth.

These results are consistent with our prior research, which showed modest changes in combined liquid wealth in the first four years of operations, mostly occurring in the first two years (Wheat, Mac, and Tremper 2021). Although we might not expect to see significant wealth generation in the first two years of a business, new businesses and their owners with modest combined balances do not appear poised to generate wealth. However, those in the fourth quartile were not only more likely to start a business but also had more resources to invest in their new businesses. The owners in this group had typical firm balances of over $8,000, compared to typical firm balances of $1,000 in the first quartile. While these larger businesses may be better positioned to generate wealth for their owners, their owners were already in the highest quartile of liquid wealth before starting their firms.6

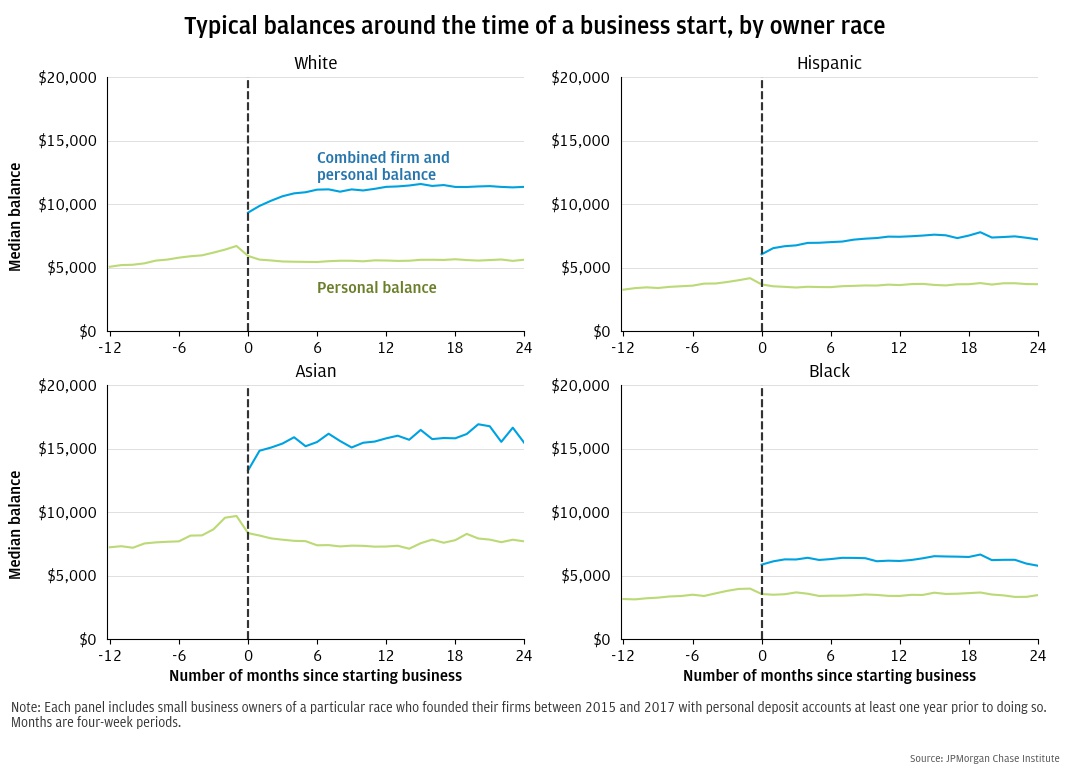

This finding is particularly important when considering the differences in liquid wealth by race. Finding 1 showed that while wealthy Black and Hispanic people were similarly likely to start a business as wealthy White or Asian people, the typical Black or Hispanic founder started their businesses with much less liquid wealth than their typical White or Asian peers. These differences may lead to fewer growth and investment opportunities for Black and Hispanic small business owners, and therefore, fewer opportunities for the firms to generate wealth for their owners. Figure 5 shows the liquid wealth of the typical Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White small business owner over the 36-month period around a small business start.

Figure 5: Black and Hispanic business owners have lower liquid wealth

The comparatively lower level of starting wealth for Black or Hispanic small business owners may mean that these founders are less able than their White or Asian peers to invest in their businesses. Indeed, the initial personal balance of the typical White or Asian small business owner tended to decrease more than the typical Black or Hispanic small business owner. Existing wealth inequities could influence the ability of Black or Hispanic founders to invest in their businesses and generate meaningful wealth.

Finding 2 shows that, at least in a firm’s early days, small business ownership may not substantively increase liquid wealth or, by extension, reduce the racial wealth gap. Relatively wealthy individuals are not only more likely to start new businesses, but they are also able to invest more and potentially generate wealth in the future. Although small business owners tended to have higher liquid wealth than wage earners with similar demographics, there were nevertheless large discrepancies between Black, Hispanic, Asian, and White small business owners. Typical Black and Hispanic business owners founded their firms with less initial wealth, limiting their ability to invest in and grow their businesses. Moreover, lower firm balances are correlated with higher exit rates. Black- and Hispanic-owned small businesses, which tend to have lower balances, are more likely to close in the first three years of business than White-owned ones (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2020).

Small business owners tend to be wealthier than their counterparts who do not own businesses. However, the comparison is often between owners of successful businesses and those who are not currently business owners, which include former business owners. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic about 7.5 percent of firms exited annually (Crane et al. 2021), and most small businesses exit within six years of opening (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2018), so it is important to understand the effects of firm exit on wealth, and more broadly, differences in financial outcomes for owners of small businesses that exit as compared to those that survive. In order to understand these differences, we compared the liquid wealth trajectories of business owners around the time their firms closed to the same outcomes for a random sample of owners with surviving businesses.

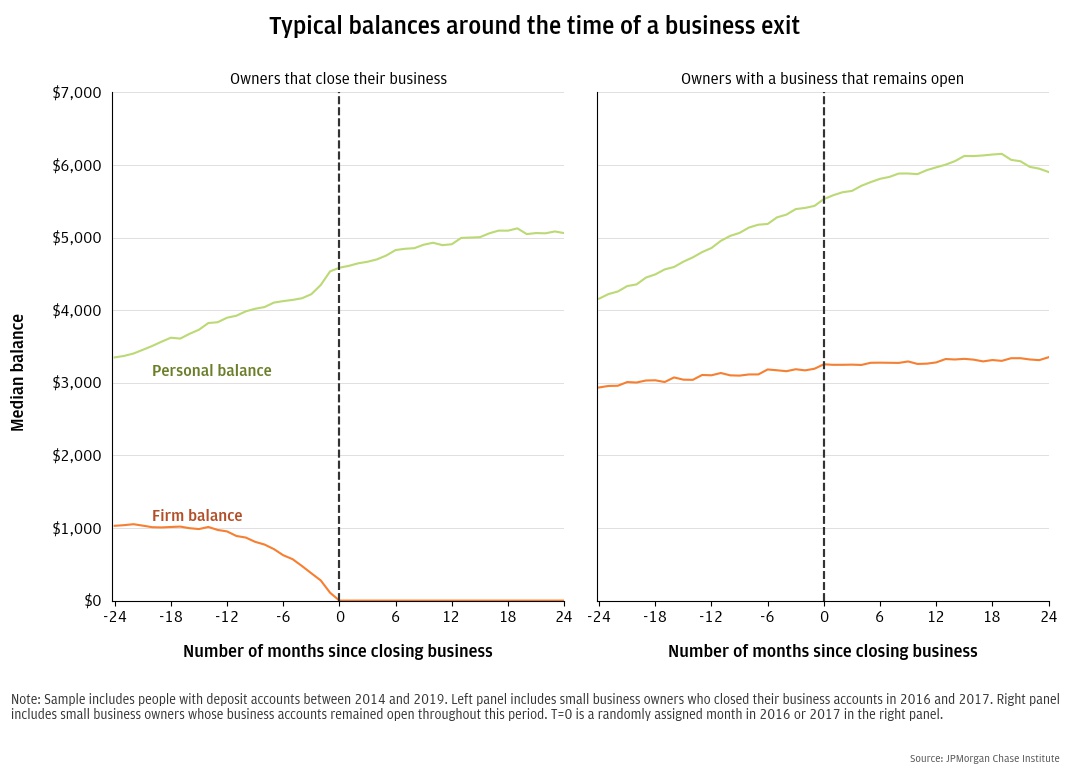

We identified about 13,500 small business owners who closed their business in 2016 and 2017 and tracked their liquid wealth before and after the exit. Figure 6 shows the liquid wealth of these small business owners and a comparison group of about 52,000 firms that did not exit. Time zero for owners of exiting firms was the month in which the firm closed. For surviving firms, time zero was assigned to a random month in 2016 or 2017.

Figure 6: Owners of small businesses that close have less liquid wealth than owners of businesses that stay open

First, the typical firm approaching exit experienced a gradual decline in balances over many months rather than a punctuated exit event. A possible reason that firm balances might decline as a business approaches exit is that owners are transferring funds back to their personal accounts. However, Figure 6 suggests that this was not typically the case. Although the balance of the typical exiting small business owner increased in the final 24 months of a business, it appears to have done so at a similar rate as the personal balance of the typical small business owner who did not exit. Rather than draws to a personal account, declining firm balances may instead be the result of decreased business activity and the payment of final expenses. This is consistent with surveys showing that 25 percent of employer small businesses reported low sales or cash flows as their reason for exiting—the most common answer chosen (Headd 2018).

Second, small businesses that stayed open had relatively stable higher balances compared to those that closed. The typical balance of a firm that did not exit was about $2,000 higher than that of the typical exiting firm, and low firm balances may be related to firm exit (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2020).

In order to build wealth, small businesses must survive long enough to do so. Consistent with previous research indicating that small businesses with regular cash flows or sufficient balances to withstand volatile cash flows were more likely to survive (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2018), the liquid wealth of owners of surviving firms was higher than that of exiting firms. However, as Finding 2 showed, higher balances were associated with firms founded by those who were already relatively wealthy. Moreover, aspiring Black and Hispanic entrepreneurs have lower wealth, and their businesses tend to have lower balances, making it more difficult for them to survive and generate wealth for their owners.

As policymakers consider the role of small business ownership in creating wealth and reducing the racial wealth gap, we offer our findings, which illustrate the how initial liquid wealth influences who starts small businesses, how owners invest in their businesses, and how firm exits affect owners. We also offer the following implications of our findings:

Mitigate the risk of starting a small business to expand entrepreneurship opportunities to more people. Starting a small business is a risky endeavor. Aspiring entrepreneurs must weigh the potential consequences of giving up a regular paycheck, investing their own funds, or starting over again should their businesses not survive. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that those with more liquid wealth are also more likely to start businesses: their savings can mitigate these risks. However, policymakers could consider policies that serve similar functions, thereby making small business ownership a viable path for more Americans. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic unemployment insurance was expanded to include those who lost their businesses. Similar and permanent policies could mitigate the risk to owners if their firms do not survive. Programs like the Self Employment Assistance,7 which support existing unemployed people as they seek to start a business, should be studied more to understand how they might alleviate the pressure on personal funds.

Microloans and grants could provide the capital for lower-wealth Americans to start businesses that are better positioned to generate wealth. Higher-wealth people were not only more likely to start small businesses, but they were also able to invest more into their firms. Their personal wealth may have also allowed them to start different kinds of firms—ones that were larger and perhaps better positioned to generate wealth—compared to those founded by their peers with lower levels of liquid wealth. The difference in initial wealth between the highest liquid wealth quartile and the lower quartiles is about $10,000 to $20,000. These are substantial amounts in terms of personal wealth, but they would be considered relatively small business loans and grants. These funds could allow an aspiring entrepreneur with little personal wealth to start and invest in a new business the way someone with higher liquid wealth could, providing more opportunities to start the kinds of businesses that are more likely to generate wealth. Programs targeting low-income or majority-minority neighborhoods could be particularly helpful for Black and Hispanic business owners, who typically start firms with less cash, which may limit their opportunities for wealth creation.

Some entrepreneurs may see material wealth gains relative to their alternatives as wage earners. For some Americans who face potential discrimination in the labor market, small business ownership could provide an important avenue for income. For example, recent immigrants or returning citizens may find that entrepreneurship offers more opportunities to earn a living and build wealth. More research is needed to understand the dynamics between the labor market and entrepreneurship.

Christnacht, Cheridan, Adam Smith, and Rebecca Chenevert. 2018. “Measuring Entrepreneurship in the American Community Survey: A Demographic and Occupational Profile of Self-Employed Workers.” Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division Working Paper Number 2018-28. U.S. Census Bureau.

Crane, Leland D, Ryan A Decker, Aaron Flaaen, Adrian Hamins-Puertolas, and Christopher Kurz. 2021. “Business Exit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Non-Traditional Measures in Historical Context.” Finance and Economic Discussion Series, Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Evans, David and Boyan Jovanovic. 1989. “An Estimated Model of Entrepreneurial Choice under Liquidity Constraints. Journal of Political Economy 808-827.

Fairlie, Robert and Sameeksah Desai. 2021. National Report on Early-Stage Entrepreneurship in the United States: 2020. Kauffman Indicators of Entrepreneurship, Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation: Kansas City.

Fairlie, Robert and Harry Krashinsky. 2012. “Liquidity Constraints, Household Wealth, and Entrepreneurship Revisited.” The Review of Income And Wealth 279-306.

Farrell, Diana, Fiona Greig, Chris Wheat, Max Liebeskind, Peter Ganong, Damon Jones, and Pascal Noel. 2020. “Racial Gaps in Financial Outcomes: Big Data Evidence.” JPMorgan Case Institute.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2018. “Growth, Vitality, and Cash Flows: High-Frequency Evidence from 1 Million Small Businesses.” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2019. “Gender, Age, and Small Business Financial Outcomes.” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2020. “Small Business Owner Race, Liquidity, and Survival.” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Gartner, William B, Casey J Frid, and John C Alexander. 2012. "Financing the emerging firm." Small Business Economics 745-761.

Greig, Fiona, Erica Deadman, and Pascal Noel. 2021. “Family cash balances, income, and expenditures trends through 2021: A distributional perspective.” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Greig, Fiona, Erica Deadman, and Tanya Sonthalia. 2021. “Household Finances Pulse: Cash Balances during COVID-19.” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Headd, Brian. 2021. “The Importance of Small Business Ownership to Wealth.” United States Small Business Administration.

Headd, Brian. 2018. "Why do Businesses Close?" United States Small Business Administration. https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/06192013/Small_Biz_Facts_Why_Do_Businesses_Close_May_2018_0.pdf.

Hurst, Erik, and Annamaria Lusardi. 2004. "Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship." Journal of Political Economy 319-347.

McIntosh, Kriston, Emily Moss, Ryan Nunn, and Jay Shambaugh. 2020. “Examining the Black-white wealth gap.” https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/02/27/examining-the-black-white-wealth-gap/.

United States Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy. 2022. 2022 Small Business Financing FAQ. Washington, DC: United States Small Business Administration.

United States Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy. 2021. 2021 Frequently Asked Questions. Washington, DC: United States Small Business Administration.

Wheat, Chris, and Chi Mac. 2021. “Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity?” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Wheat, Chris, Chi Mac, and Nich Tremper. 2021. “Small business ownership and liquid wealth.” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

We thank Noah Forougi for his hard work and vital contributions to this research. Additionally, we thank Emily Rapp for her support. We are indebted to our internal partners and colleagues, who support delivery of our agenda in a myriad of ways and acknowledge their contributions to each and all releases.

We would like to acknowledge Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., for his vision and leadership in establishing the Institute and enabling the ongoing research agenda. We remain deeply grateful to Demetrios Marantis, Head of Corporate Responsibility, Heather Higginbottom, Head of Research & Policy, and others across the firm for the resources and support to pioneer a new approach to contribute to global economic analysis and insight.

This material is a product of JPMorgan Chase Institute and is provided to you solely for general information purposes. Unless otherwise specifically stated, any views or opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors listed and may differ from the views and opinions expressed by J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS) Research Department or other departments or divisions of JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates. This material is not a product of the Research Department of JPMS. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively J.P. Morgan) do not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. No representation or warranty should be made with regard to any computations, graphs, tables, diagrams or commentary in this material, which is provided for illustration/reference purposes only. The data relied on for this report are based on past transactions and may not be indicative of future results. J.P. Morgan assumes no duty to update any information in this material in the event that such information changes. The opinion herein should not be construed as an individual recommendation for any particular client and is not intended as advice or recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, or strategies for a particular client. This material does not constitute a solicitation or offer in any jurisdiction where such a solicitation is unlawful.

Wheat, Chris, Chi Mac, and Nicholas Tremper. 2022. “Small Business Owner Liquid Wealth at Firm Startup and Exit.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/insights/business-growth-and-entrepreneurship/small-business-ownership-liquid-wealth-startup-exit

Modeled demographic data was obtained in 2021 from a third party for the JPMorgan Chase Institute to conduct economic research examining financial outcomes by race, ethnicity, and gender. The demographic data was matched to internal banking records using encrypted quasi-identifiers. This de-identified file that contains banking records and demographics is only available to the JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Month is equal to a 28-day period. Doing so creates equally sized event time periods while also avoiding instances where people may see different balances because of the calendar. For example, five Fridays in a month might show higher balances in months where someone is paid three times instead of their regular twice.

The share of firms owned by women in this sample is higher than the shares previously reported (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2019). This is due to different sources of gender data that became available after that report was published.

For example, if a business owner opens an account on June 1st, 2016, our observation window starts at July 1st, 2015 and ends on January 12, 2016, reflecting the period that is six to twelve months prior to the business start. This is a total of 7 months, where each month is a 28-day period.

These rates do not necessarily reflect general business formation rates. For example, our sample consists of small business owners who founded one, and only one firm, during a three-year period between 2015 and 2017. In addition, the rest of the sample is comprised entirely of wage earners with regular direct deposit payroll income, which may make them less likely to start a small business. Other researchers have estimated monthly startup rates of about 0.3 percent, with annual rates that may be six to eight times higher (Fairlie and Desai 2021). Annual rates are not twelve times higher because individuals may start and exit multiple times.

Our sample excluded businesses with multiple owners, which may be larger and perhaps more likely to generate wealth for their owners. This restriction was necessary to attribute firm balances to the respective owners and combine owner and firm balances. However, most small businesses are very small. Over 80 percent are nonemployers, and much of the growth in the small business sector can be attributed to these nonemployer firms (U.S. Small Business Administration 2021). Our sample and results are illustrative of typical small businesses owners, as the vast majority of small businesses are very small.

Authors

Chris Wheat

President, JPMorganChase Institute

Chi Mac

Business Research Director

Nicholas Tremper

Senior Research Associate