Figure 1: Nearly 8 percent of families earned income from the Online Platform Economy in the year before the pandemic

Just a decade ago, the Online Platform Economy comprised a handful of marketplaces connecting independent sellers to buyers of physical goods. Today, we rely on platforms to find transportation to the airport, someone to walk our dog, a place to stay on vacation, and gifts for our family members. Purchasing goods and services from independent suppliers through platforms has become a routine part of daily life. In this report, we documented how families interacted with online platforms to earn money with a focus on the period between our last report in 2018 through the COVID pandemic (Farrell, Greig, and Hamoudi 2018).

Three forces at play during the pandemic make this a particularly interesting period to study the Online Platform Economy. First, workers experienced record-level job losses, especially lower-income workers. As we have previously documented, workers turn to the Online Platform Economy—transportation platforms in particular—as a source of income when they experience job loss (Farrell, Greig, and Hamoudi 2019). This might suggest that we would see new entrants into the Online Platform Economy during the pandemic or an increase in reliance on platforms as a source of income. At the same time, the pandemic made many in-person services like ride sharing much less attractive to consumers (and suppliers) which may have stemmed the inflow of new platform workers and suppliers. Similarly, non-pharmaceutical interventions like social distancing protocols limited consumers’ ability to travel and engage many in-person services. This potentially curtailed demand for many platform services and caused participants to leave their platforms.

Second, Congress dramatically expanded unemployment insurance benefits both in terms of generosity of payments and who is covered. The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program specifically covered gig workers and other self-employed workers who faced a loss of income. In addition to covering platform workers, PUA may have also provided coverage to workers who, absent PUA, wouldn’t have qualified for UI and may have turned to platform work to support themselves.

Third, the pandemic effected many lifestyle and behavior changes, including work-from-home, increased online purchasing, and increased food delivery. These changes may have increased the feasibility of, and demand for, platform work or shifted platform participants from one sector or platform to another.

This report aims to answer four questions. First, how did supply-side participation in the Online Platform Economy change during the pandemic? Second, to what extent were changes in participation driven by experienced workers versus those new to platform work? Third, how much did platform participants rely on unemployment insurance during the pandemic? Fourth, how much of platform workers’ total income comes from the Online Platform Economy?

As with previous work, we study supply-side participation in the Online Platform Economy by tracking payments from platforms into de-identified personal checking accounts (Farrell, Greig, and Hamoudi 2018). Specifically, from a universe of 30 million Chase deposit account customers, we select families who are active users of their Chase account and track payments received from 38 online platforms between April 2018 and June 2021.i

We define the Online Platform Economy as platforms that (1) connect independent suppliers to consumers of goods and services; and (2) mediate payment. We disaggregate the Online Platform Economy into four sectors: two labor sectors in which participants sell their time or skills, and two capital sectors in which participants sell goods or lease property.

Labor platforms include:

Capital platforms include:

Given the proliferation in platforms and the payment mechanisms by which participants can receive their platform earnings, we view the unique strength of our data asset as quantifying high-frequency trends (rather than levels) in platform participation and revenues, and how they are related to other aspects of a family’s financial life.

We find that nearly 8 percent of families earned income from the Online Platform Economy during the year before the pandemic, though growth in participation has slowed since March 2020. Transportation and leasing platforms took the biggest hits during the pandemic due to the departure of existing drivers and lessors, while selling platforms have continued to grow. Families with platform income prior to the pandemic, drivers in particular, were much more likely to receive unemployment insurance in 2020 and 2021 than those without. Platform income as a share of total income has been declining, but median earnings has stayed constant, suggesting an increase in overall income among platform participants during the pandemic.

We conclude that the Online Platform Economy is a crucial source of income for many families even after the shock of the pandemic. During the pandemic, the Online Platform Economy served as not just a fallback source of income in a time of potential need but also, in its own right, a source of potential risk. New workers continued to start platform work during the pandemic, allowing them to remain attached to the workforce. Many others exited platform work potentially due to a fall in consumer demand, heightened public health risk, or the availability of expanded unemployment benefits. Indeed, Online Platform Economy workers appear to be particularly vulnerable to economic shocks with extremely high rates of unemployment insurance receipt during the pandemic. Of all platform workers, drivers appear to be the group of biggest concern for policymakers from a welfare perspective. They are the most numerous group, have the lowest family incomes, were the most likely to have received unemployment insurance during 2020. The continued rise of the Online Platform Economy raises the importance of strengthening the social safety net for contingent workers and reducing the administrative burdens associated with platform income.

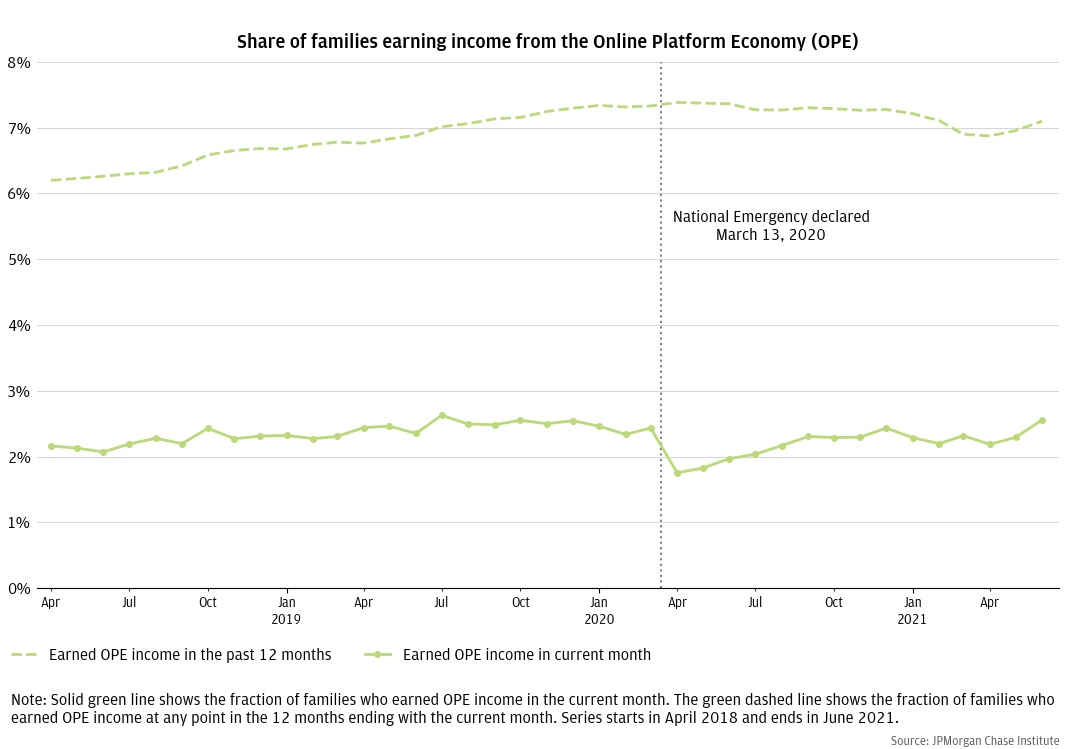

Figure 1 below shows the share of families earning Online Platform Economy income in a given month and the share earning platform income any time in the year prior to the given month. Prior to the COVID pandemic, we observed continued growth in participation in the Online Platform Economy, peaking at 2.5 percent monthly, with almost 7.5 percent of households earning platform income within the past year in January of 2020. At the onset of the pandemic, monthly participation fell from its peak to 1.9 percent, a 25 percent decrease in month-to-month participation, and then gradually recovered, nearing its peak of 2.5 percent by June of 2021.

As evident in Figure 1, there is a large difference between the share of families earning platform income in a given month versus over the prior year. This suggests that counts of active monthly users significantly understates the importance of the Online Platform Economy as a source of income over the course of the year. Our January 2020 platform participation estimates of roughly 7.5 percent of families in the prior year and 2.5 percent in the prior month fall below estimates of the prevalence of contract or alternative work arrangements from 2018 administrative tax records and the 2017 contingent worker survey but above their estimates of the Online Platform Economy (Garin and Koustas 2021; Department of Labor 2018).

Figure 1: Nearly 8 percent of families earned income from the Online Platform Economy in the year before the pandemic

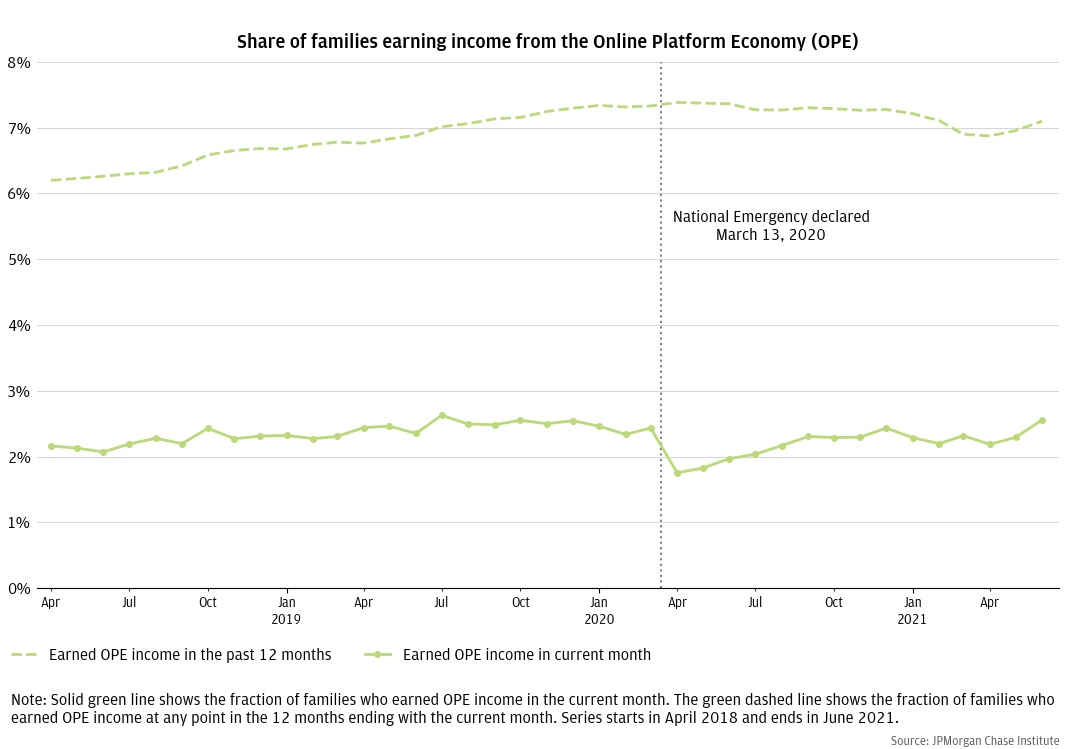

Figure 2 shows monthly supply-side participation rates by platform sector. At the onset of the pandemic, supply of drivers and lessors fell precipitously, likely due to social distancing measures, travel restrictions, and hesitancy among suppliers about the virus.

Driver participation fell by more than a third from roughly 1.5 percent to below 1 percent in April and May of 2020. Some drop in driver participation is likely due to both a decline in drivers who are willing to drive during a pandemic (supply side) and a decline in the share of people or businesses who would desire driving services (demand side). However, drivers transport not just people but also goods, such as prepared food. Further into the pandemic, as restaurants and other businesses adapted to online ordering and delivery, many rideshare drivers switched to delivery (Accenture 2021). Supply for this kind of driving may have also been higher because of not only the increase in demand but also the lower risk from the virus since it requires less contact with customers.

Figure 2: Most Online Platform Economy participants work in the transportation sector

Participation in the leasing sector dropped 50 percent, from 0.2 percent to 0.1 percent of the sample, at the onset of the pandemic. Participation gradually increased back to its pre-pandemic peak by June 2021. It is likely that that the demand for short-term leasing of properties or vehicles may have fallen due to stay-at-home orders and the overall decrease in travel.

At the same time, growth in selling platforms continued and perhaps even accelerated slightly, consistent with dramatic shift towards online purchasing during the pandemic (Wheat, Mac, and Duguid 2021). With sustained growth in selling platforms, the overall supply-side participation in the Online Platform Economy only slightly decreased.

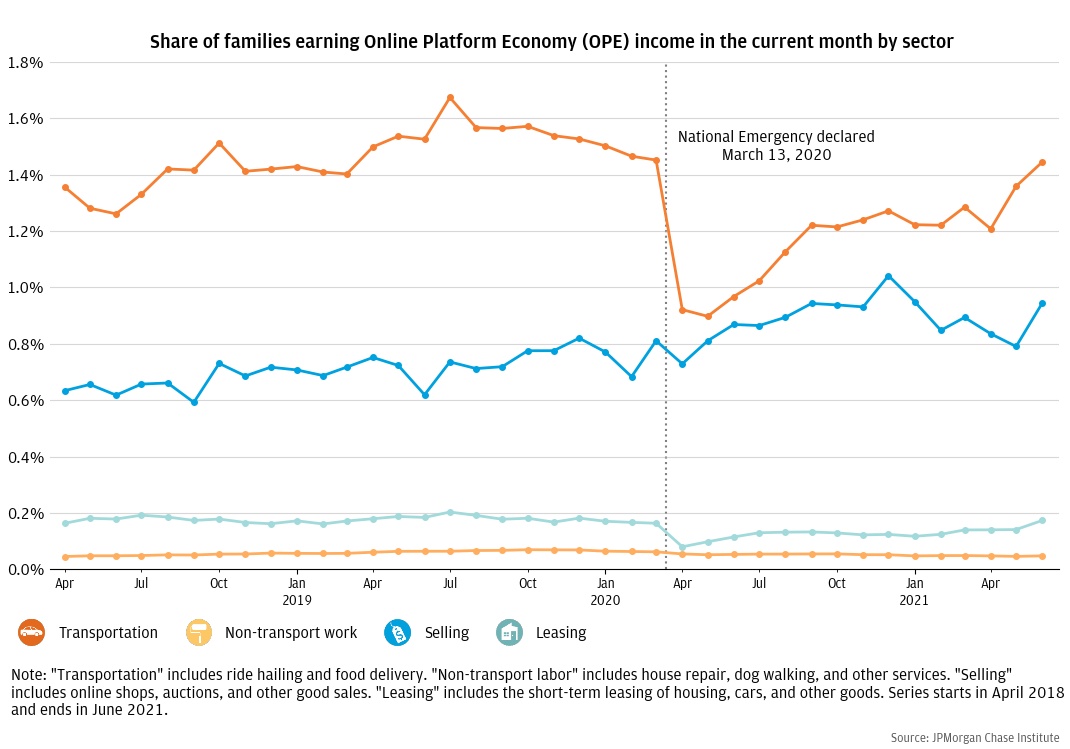

Next we explore whether changes in participation are caused by a slowdown in new entrants or an acceleration in exits among existing participants. This is an important distinction for several reasons. First, in previous work and as evidenced in Figure 1, we observe a high degree of churn among platform participants, with the majority of workers earning platform income in just a few months out of the year, often when they experience periods of unemployment (Farrell, Greig, and Hamoudi 2018). We want to know whether participants are turning to platform work in a time of need, or exiting from platform work potentially due to a fall in consumer demand, heightened public health risk, or the availability of expanded unemployment benefits.

We find evidence of both. Figure 3 disaggregates the monthly participation rate into existing participants who had already earned platform income in the prior year versus new participants who had participated in the Online Platform Economy in the current month and not earned platform income in the prior year. Focusing on drivers in the top left panel, we observe that the precipitous drop in driver participation is entirely accounted for by an acceleration in exits among existing drivers (solid line). At the same time, new drivers continued to enter platforms for the first time in a year at the roughly same pace throughout the pandemic (dotted line). We observe a similar pattern for non-transport workers (bottom left panel), who include workers engaged in both in-person and remote services.

In contrast, participation rates of both new and existing lessors fell dramatically at the start of the pandemic. This is likely again due to social distancing regulations and decreased demand for travel and hospitality services. However, the drop in new lessors, in contrast to the steady flow of new drivers, may also be tied to the kind of people who turn to leasing versus transportation platforms. As we outline in Finding 3, lessors tend to have significantly higher incomes than drivers.

Like leasing platforms, the trends in capital selling mirror wider economic shifts in consumer demand following the pandemic. Both new and experienced sellers increased their participation following the pandemic as consumers shifted to online retail. In addition, unlike leasing, the entry costs for online selling are relatively low, and people may have turned to the Online Platform Economy out of necessity to make ends meet or while working from home.

Figure 3: Experienced drivers stopped using online platforms following the pandemic but new drivers continued to take up platform work

Having documented that many existing participants left the Online Platform Economy, we next examine the extent to which platform participants received unemployment insurance. Under the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, platform workers could have become eligible for unemployment benefits due to a loss of platform income. Additionally, platform workers or their family members could have received unemployment benefits as a result of losing a non-platform job.

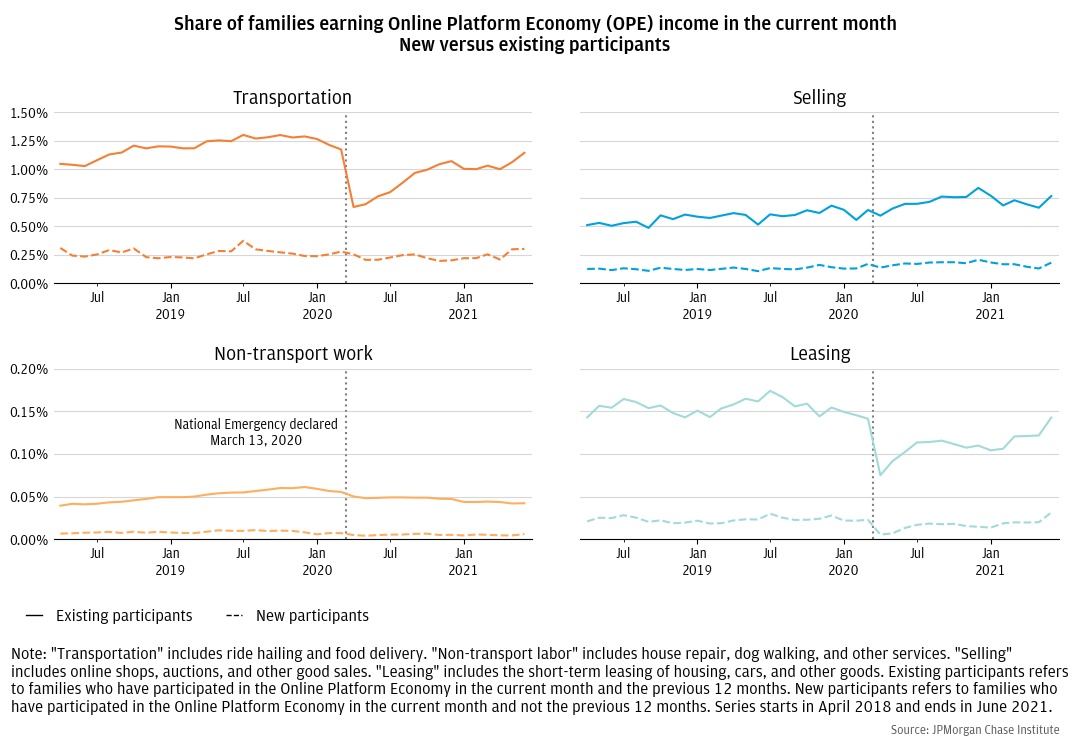

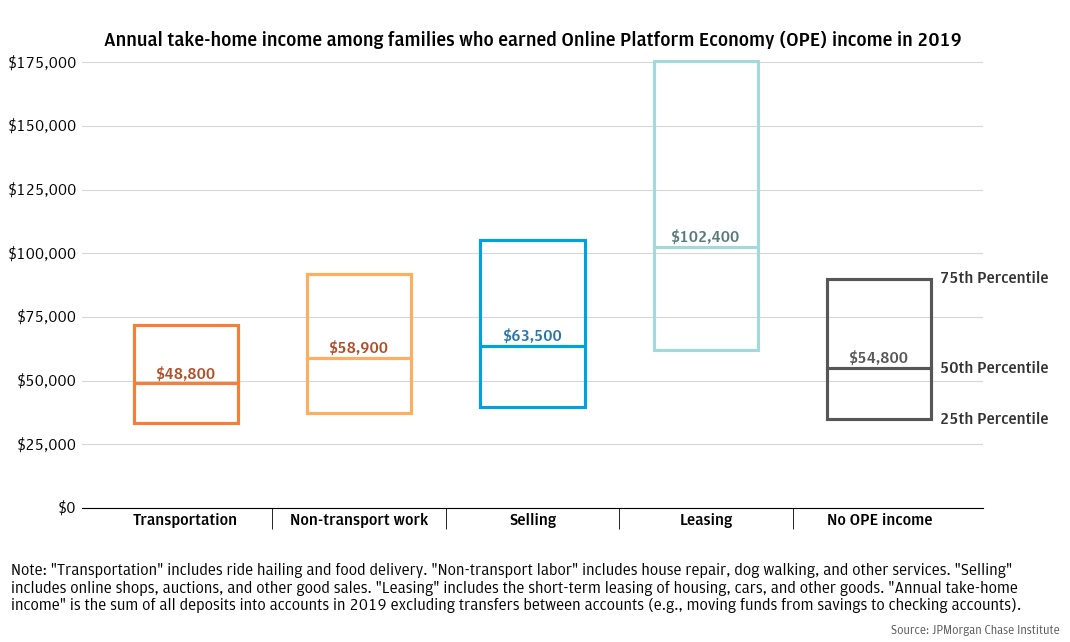

Recognizing that job losses during the pandemic were concentrated in low-income sectors, we start by documenting pre-pandemic total income in Figure 4. We find that baseline income of platform participants varies considerably by sector. In 2019, prior to the pandemic, median total take-home income was roughly $49,000 for drivers, $59,000 for non-transport workers, $64,000 for sellers, and $102,000 for lessors. Thus, intuitively, drivers tend to be lower-income workers, while lessors tend to have the highest incomes. Meanwhile, people with no platform income in 2019 had a median total income of $55,000, slightly higher than platform transport workers.

Figure 4: Transportation workers have incomes slightly lower than the general population while capital lessors have significantly higher incomes

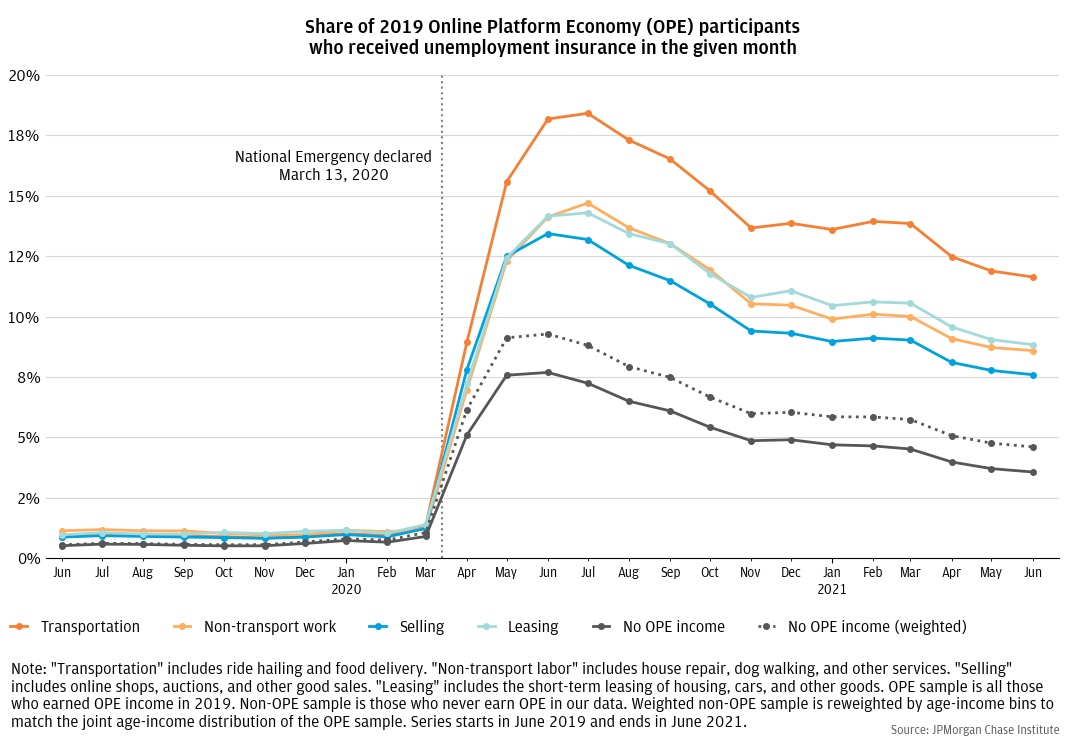

These stark patterns in 2019 income suggest that the economic shock of the pandemic may have affected platform participants very differently across sectors because of differences in the nature of not just their platform work but also their non-platform work. To explore this, we look at all families who had platform income in 2019 and calculate how many received their unemployment insurance (UI) over the course of the pandemic. These UI rates are plotted in Figure 5, alongside the UI rates of families who received no platform income in 2019. In this sample, we are unable to distinguish between people who received traditional UI and those who received PUA.

Figure 5: Many more Online Platform Economy workers received unemployment insurance than the general population

Overall, we see significantly higher UI rates among platform participants relative to the non-platform group. At its peak, the UI receipt rate of drivers was just under 19 percent, over twice the rate of the non-platform group. UI receipt rate among platform participants in other sectors are also elevated, peaking between 13 and 15 percent.

It is important to note that the demographics of platform participants may be different from the non-platform population, and this may in turn be driving some of the differences in UI rates. For example, if platform drivers are younger than the general work force and all young workers were hit relatively hard by the pandemic recession, that may explain why the platform drivers have such high UI rates. To explore how much demographics are driving the difference in UI rates, we re-weight the non-platform sample so that it has the same joint age and income distribution as the platform sample. The dashed gray line in Figure 5 shows the UI rate of this re-weighted sample.

Re-weighting the non-platform sample to have the same age and income profile as platform participants closes a fraction of the gap in UI receipt between the two groups.

A number of other factors could be driving these differences, such as industry, geography, or the nature of the workers themselves. That is, workers with non-platform jobs that were more irregular or directly impacted by the pandemic might be more likely to moonlight as platform drivers, workers, and sellers. As such, the pandemic-induced recession, which disproportionately caused job losses among lower-income workers, likely affected platform participants more than the general population. It is also possible that platform workers, facing a loss of consumer demand and a public health risk, applied for and received Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) which expanded UI eligibility to self-employed and contingent workers.

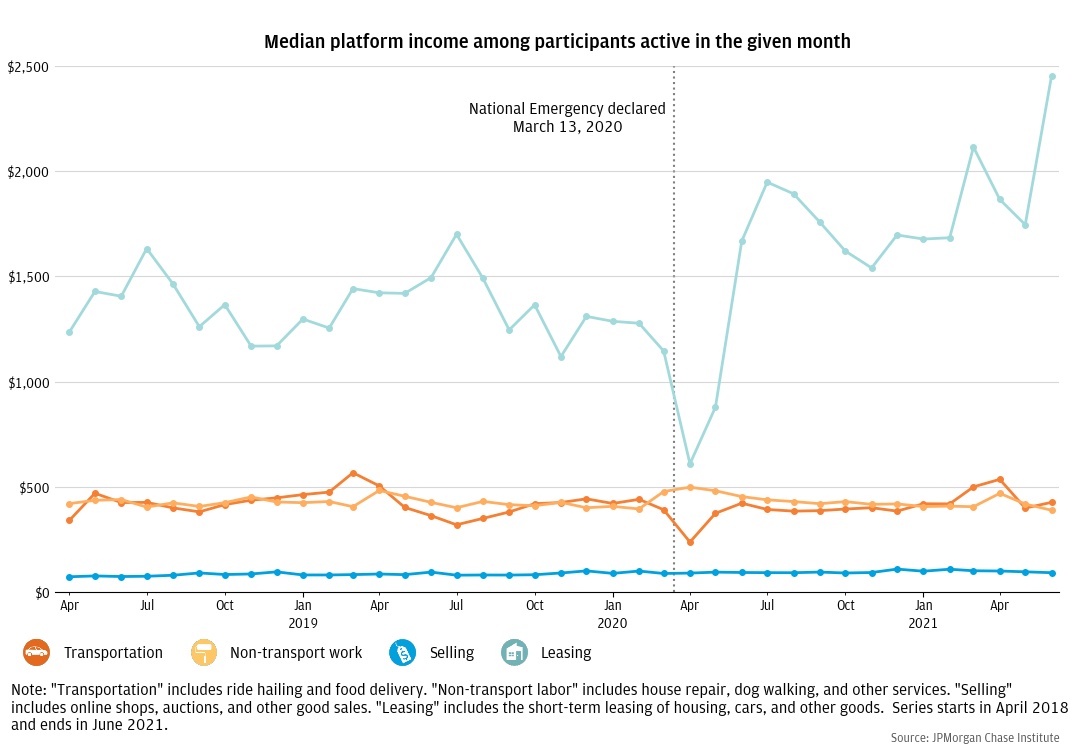

Next we return to active platform participants and document trends in monthly platform revenues since 2018. Figure 6 shows median platform income among families who earned any income in the given platform sector in the current month. It is important to note these earnings represent revenues to participating families, and not profits net of expenses. Additionally, given the dynamic pricing models commonly deployed by platforms, a change in revenues could reflect a change in prices, units sold, or both.

Median monthly platform income for lessors was roughly $1,300 or at least three times higher than monthly revenues in the other three platform sectors. Lessor revenues were steady leading up to the pandemic, fell briefly at the onset of the pandemic, and then rose sharply. The subsequent rise in earnings is likely due to a change in who is actively participating in the online platforms. Recall that Figure 3 shows a steep drop in both new and experienced lessors. Families more involved in platform leasing, like those with more units to lease, derive more total revenue from leasing and would be more likely to remain in the sample or be the quickest to rebound. In addition, it could reflect an increase in prices or longer-term rentals as families adjusted to pandemic lifestyle.

For drivers, the trend in monthly platform revenues is also generally flat before the pandemic, but active drivers saw a 40 percent drop in platform revenues in April 2020. Given the drop in the supply of drivers evident in Figure 2, the fall in revenues is evidence of a fall in consumer demand for transportation services. Revenues among active drivers quickly rebounded in June 2020 to near pre-pandemic levels, even as driver participation rates were still depressed. Insofar as Figure 6 documents total platform-derived income, the product of hourly earnings and total hours worked, it cannot inform us about whether drivers are working longer hours earning less per trip in order to sustain revenues.

Figure 6: When engaging in online platform work, drivers earn about $400 per month

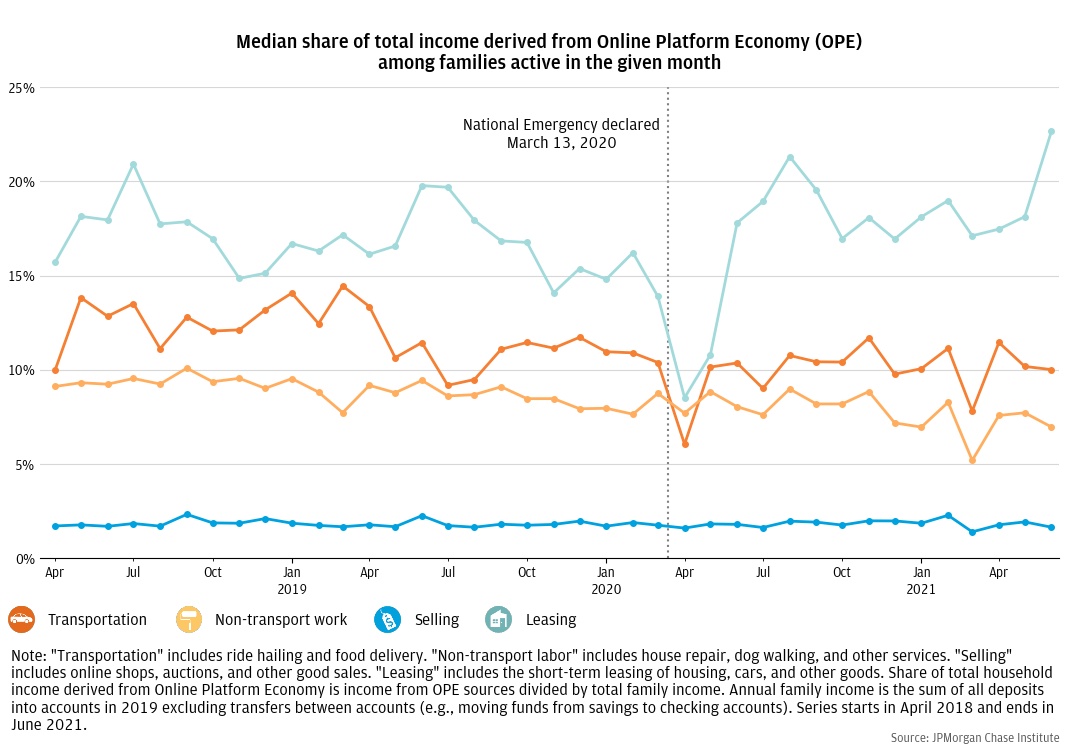

We can, however, measure how important platform-derived income is to families’ overall financial health by calculating what fraction of a family’s income comes from platform sources. We do this in Figure 7, which takes each family’s ratio of platform sector income to total family income and plots the median value of those ratios across families participating in the given platform sector in the given month.

Figure 7: The median driver earns roughly 10 percent of their family’s total income from transportation platforms.

The median lessor derived between 15 and 20 percent of their total family income through leasing platforms prior to the pandemic. This share rose slightly since the onset of the pandemic to closer to 20 percent. This increase in platform income as a share of total family income is again probably due to a change in who is participating, with fewer lessors entering the sector following the pandemic. But even before the post-pandemic increase, lessors had the largest platform income share across all platform sectors; that is, lessors earn a larger portion of their total family income via leasing platform than participants in any other platform sector.

The sectors in which platform income contributes the next highest share to family income are transportation and non-transport work. Before the pandemic, platform income ranged between 10 and 15 percent of total family income for drivers and 9 percent for non-transport workers. As shown in Figure 4, drivers and non-transport workers tend to have the lowest incomes of all platform workers. This suggests that the availability of online platforms is much more important to drivers and non-transport workers than it is for other participants from the standpoint of family welfare and quality of life.

After the onset of the pandemic, platform income share for drivers dipped slightly, hovering more consistently around 10 percent. Non-transport workers follow a similar pattern over time, platform income share dropping from 9 percent to 7 percent by June 2021. These trends could reflect a change in the family income profile of drivers and non-transport workers as experienced participants left and new participants arrived, as we saw in Figure 3. Additionally, as we have documented elsewhere, lower-income families saw an increase in their total family income during the pandemic due to government income supports, including both unemployment insurance and stimulus (Greig, Deadman, and Noel 2021). Thus the decrease in platform income as a share of total family income among drivers and non-transport workers could simply reflect an increase in the total family income. This is particularly likely, given the high rates of UI receipt documented in Figure 7 and the presence UI supplements, which caused many low-income workers to receive more in UI benefits than their prior income (Ganong, Noel, and Vavra 2020).

By contrast, platform sellers make relatively little of their income via online platforms, with the median share ranging between 1 and 2 percent. This, along with the relatively higher total incomes of platform sellers, suggests that online selling is a secondary source of income that is less critical to the financial health of these families.

The Online Platform Economy is crucial source of income for many families even after the shock of the pandemic. At its peak, almost 8 percent of families earned platform income in any 12 month window. This is especially true for drivers, who represent the lion’s share of supply-side platform participants and have the smallest total family incomes. Additionally, lessors derive the highest revenues and the largest share of their total family income from platforms.

During the pandemic the Online Platform Economy served as not just a fallback source of income in a time of potential need but also, in its own right, a source of potential risk. New workers continued to start platform work during the pandemic, allowing them to remain attached to the workforce. Many others exited platform work potentially due to a fall in consumer demand, heightened public health risk, or the availability of expanded unemployment benefits.

Indeed, Online Platform Economy workers appear to be particularly vulnerable to economic shocks with extremely high rates of unemployment insurance receipt during the pandemic. Almost one in five drivers in 2019 was receiving unemployment insurance at the beginning of the pandemic. Of all platform workers, drivers appear to be the group of biggest concern for policymakers from a welfare perspective. They are the most numerous group, have the lowest family incomes, were the most likely to have received unemployment insurance during 2020.

The continued rise of the Online Platform Economy raises the importance of strengthening the social safety net for contingent workers and reducing the administrative burdens associated with platform income. The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program was an important expansion of unemployment insurance during COVID-19 pandemic, representing roughly 40 percent of UI claims before it was ended in September 2021. However, recipients of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program faced significant delays in receiving unemployment benefits (Greig et al. 2021), and families who had to wait longer for jobless benefits cut their consumption more dramatically (Farrell et al. 2020). Reducing administrative hassles associated with verifying platform income for the purposes of filing taxes, qualifying for social safety net programs, or gaining access to credit, could materially improve and simplify the financial lives of platform workers.

Accenture. 2021. “Platforms Work: Research with workers using the Uber app during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.” www.platformsworkreport.com.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2018. “Contingent and Alternative Employment Arrangements – May 2017.” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/conemp.pdf

Current Population Survey staff. 2018. "Electronically mediated work: new questions in the Contingent Worker Supplement," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 2018, mlr.2018.24.

Farrell, Diana, Fiona Greig, and Amar Hamoudi. 2018. "The Online Platform Economy in 2018: Drivers, Workers, Sellers and Lessors." JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/institute/pdf/institute-ope-2018.pdf

Farrell, Diana, Fiona Greig, and Amar Hamoudi. 2019. “Bridging the Gap: How families Use the Online Platform Economy to Manage their Cash Flow.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. institute.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/labor-markets/report-bridging-the-gap.

Farrell, Diana, Peter Ganong, Fiona Greig, Max Liebeskind, Pascal Noel, and Joseph Vavra. 2020. “Consumption Effects of Unemployment Insurance during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/labor-markets/unemployment-insurance-covid19-pandemic

Ganong, P., Noel, P., & Vavra, J. (2020). “US unemployment insurance replacement rates during the pandemic.” Journal of Public Economics 191, 104273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104273

Greig, Fiona, Erica Deadman, and Pascal Noel. 2021. “Family cash balances, income, and expenditures trends through 2021: A Distributional Perspective.” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Greig, Fiona, Daniel M. Sullivan, Peter Ganong, Pascal Noel, and Joseph Vavra. 2021. “When unemployment insurance benefits are rolled back: Impacts on job finding and the recipients of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Program.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/institute/pdf/when-unemployment-insurance-benefits-are-rolled-back-research-brief.pdf

Wheat, Chris, Chi Mac, and James Duguid. 2021. “Retail Spending Response to Local Conditions during COVID-19.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/cities-local-communities/retail-spending-response-to-local-conditions-during-covid-19

We thank our research team, especially Bernard Ho, for his hard work and contribution to this research. Additionally, we thank Guillaume Kasten-Sportes, Sarah Kuehl, Anthony Rivera, Anna Garnitz, Emily Rapp, and Stephen Harrington for their support. We are indebted to our internal partners and colleagues, who support delivery of our agenda in a myriad of ways, and acknowledge their contributions to each and all releases.

We are also grateful for the invaluable input we received from Adam Rosen and team at Steaddy in updating our Online Platform Economy data asset. We are deeply grateful for their generosity of time, insight, and support.

We would like to acknowledge Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., for his vision and leadership in establishing the Institute and enabling the ongoing research agenda. We remain deeply grateful to Peter Scher, Vice Chairman, Demetrios Marantis, Head of Corporate Responsibility, Heather Higginbottom, Head of Research & Policy, and others across the firm for the resources and support to pioneer a new approach to contribute to global economic analysis and insight.

This material is a product of JPMorgan Chase Institute and is provided to you solely for general information purposes. Unless otherwise specifically stated, any views or opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors listed and may differ from the views and opinions expressed by J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS) Research Department or other departments or divisions of JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates. This material is not a product of the Research Department of JPMS. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively J.P. Morgan) do not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. The data relied on for this report are based on past transactions and may not be indicative of future results. The opinion herein should not be construed as an individual recommendation for any particular client and is not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, or strategies for a particular client. This material does not constitute a solicitation or offer in any jurisdiction where such a solicitation is unlawful.

Greig, Fiona and Daniel M. Sullivan, 2021. “The Online Platform Economy through the Pandemic.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/insights/careers-and-skills/online-platform-economy-through-the-pandemic

Our unit of analysis is a de-identified primary checking account holder, which we subsequently refer to as family. An account is included in our sample in each month starting with April 2018 and ending with June 2021, as long as we observe at least five transactions from its checking account in that month and the account has a total annualized income of at least $12,000 per calendar year. These inclusion criteria provide confidence that the account is a major financial tool for the family, and therefore that the account activity we observe provides a reasonably complete view of the family’s financial life.

Fiona Greig

Former Co-President

Daniel M. Sullivan

Consumer Research Director, JPMorganChase Institute