About one in five U.S. workers received unemployment insurance benefits in June 2020, which is five times greater than the highest UI recipiency rate previously recorded. Yet little is known about how unemployment benefits are affecting the economy today. To fill this gap, we study the consumption of benefit recipients during the pandemic.

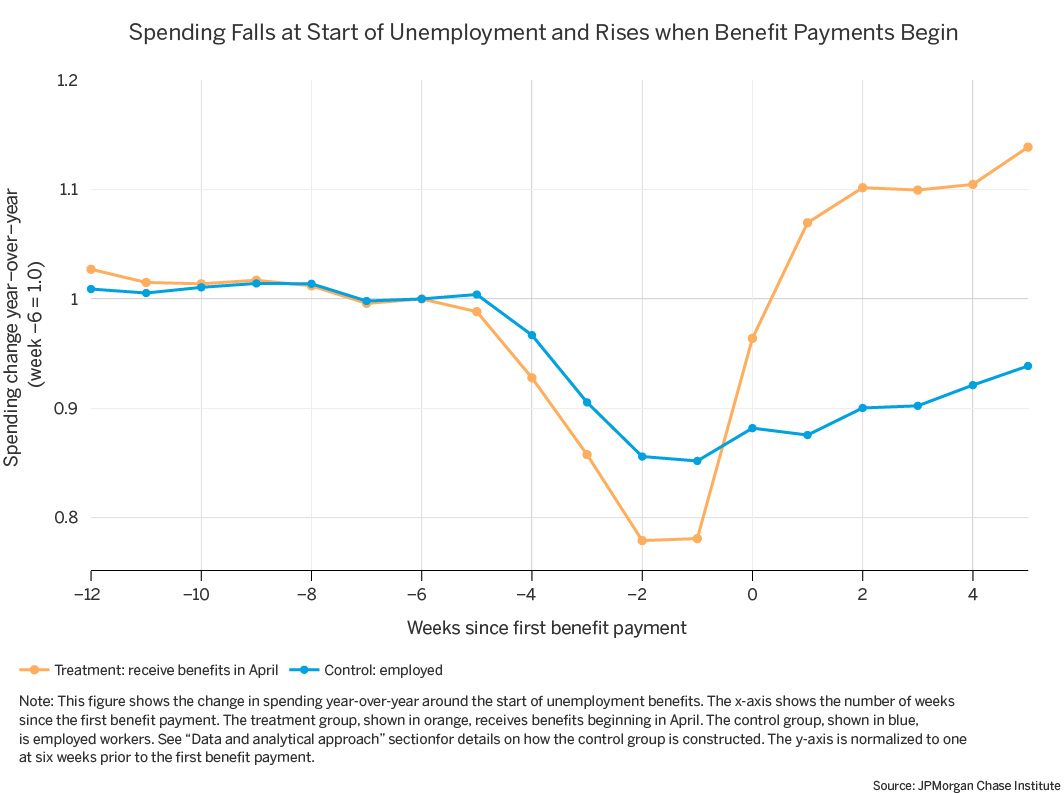

In normal times, spending among unemployment benefit recipients falls by about seven percent in response to unemployment because typical benefits replace only a fraction of lost earnings. However, in March 2020, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act added a $600 weekly supplement to state unemployment benefits, replacing lost earnings by more than 100 percent for two-thirds of unemployed workers eligible, by some estimates. As a result, for benefit spells which begin after workers receive this supplement, we find dramatically different spending patterns for the unemployed compared to normal times. Although average spending fell for all households as the economy shut down at the start of the pandemic, we find that unemployed households actually increased their spending beyond pre-unemployment levels once they began receiving benefits. The fact that spending by benefit recipients rose during the pandemic instead of falling, like in normal times, suggests that the $600 supplement has helped households to smooth consumption and stabilized aggregate demand.

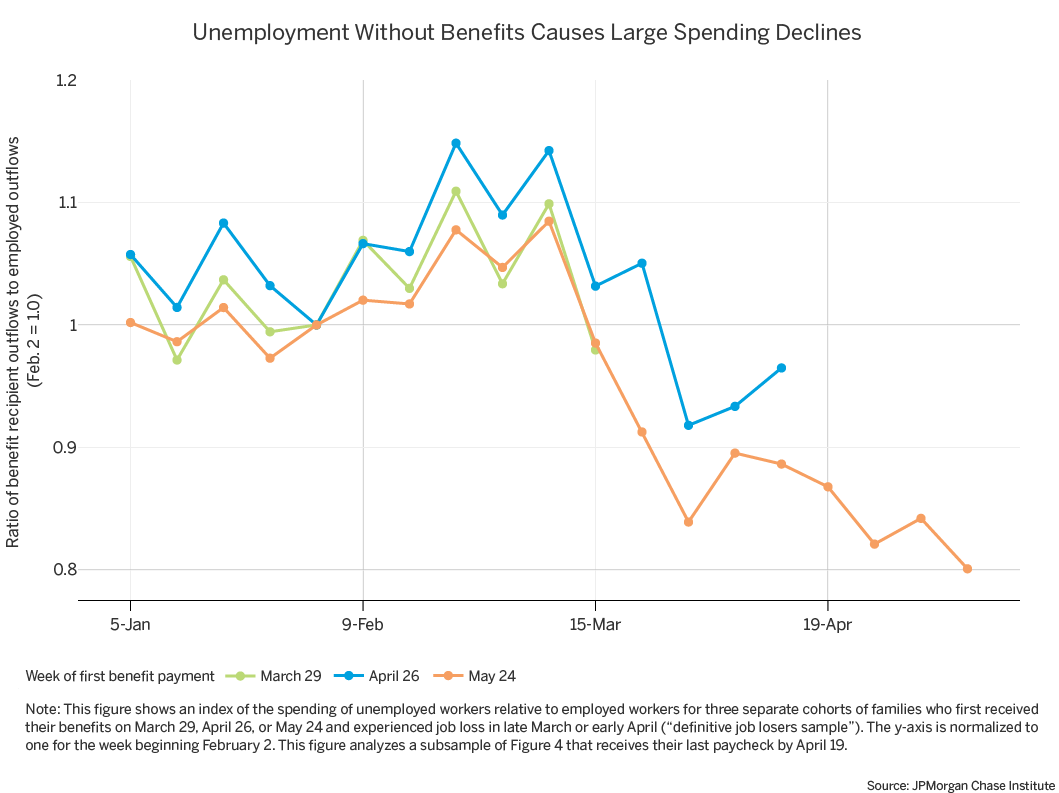

We also examine spending patterns of the unemployed while waiting for benefits to arrive. Households that receive benefits soon after job loss show no relative decline in spending, while households that wait two months to receive benefits due to processing delays have large spending declines. Compared to the employed, spending falls by 20 percent prior to receiving benefits. This suggests that delays have imposed substantial hardship on benefit recipients.

The $600 supplement to unemployment insurance benefits is scheduled to expire at the end of July. Our estimates suggest that expiration will result in large spending cuts, with potentially negative effects on both households and macroeconomic activity. The estimates also provide a guide to projecting the economic consequences of alternative supplement levels. Finally, our results also underscore the importance of making unemployment benefits broadly available and bolstering states’ ability to process claims promptly.