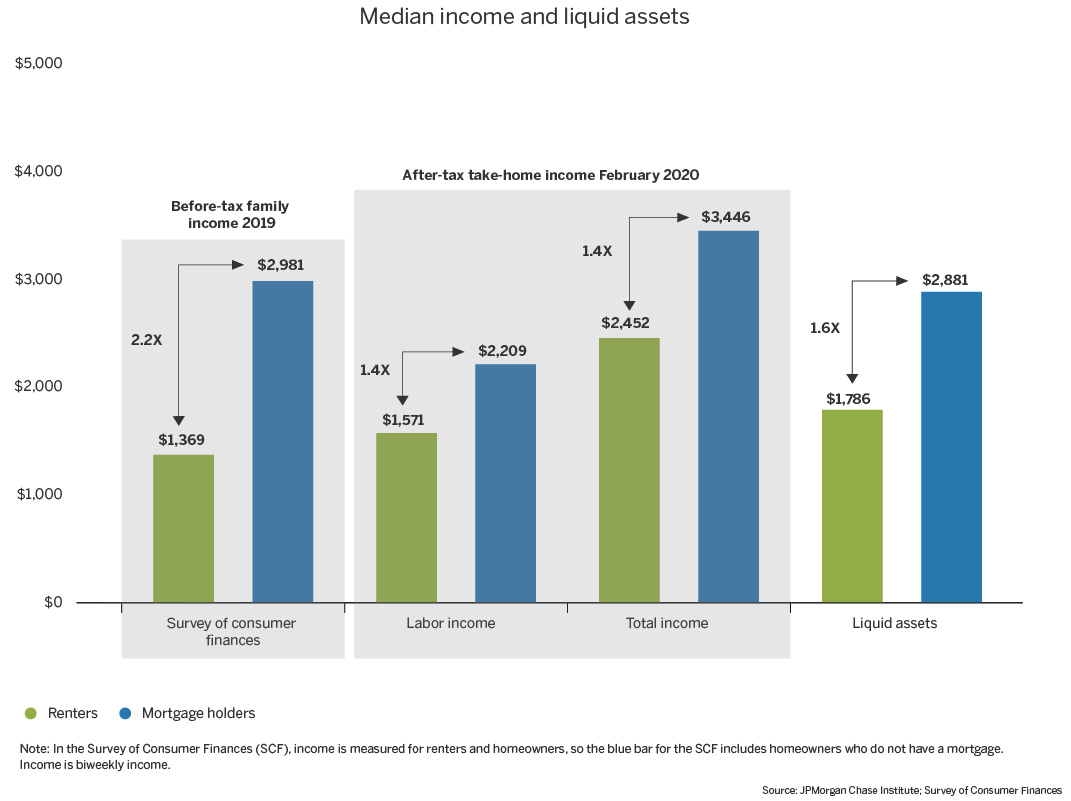

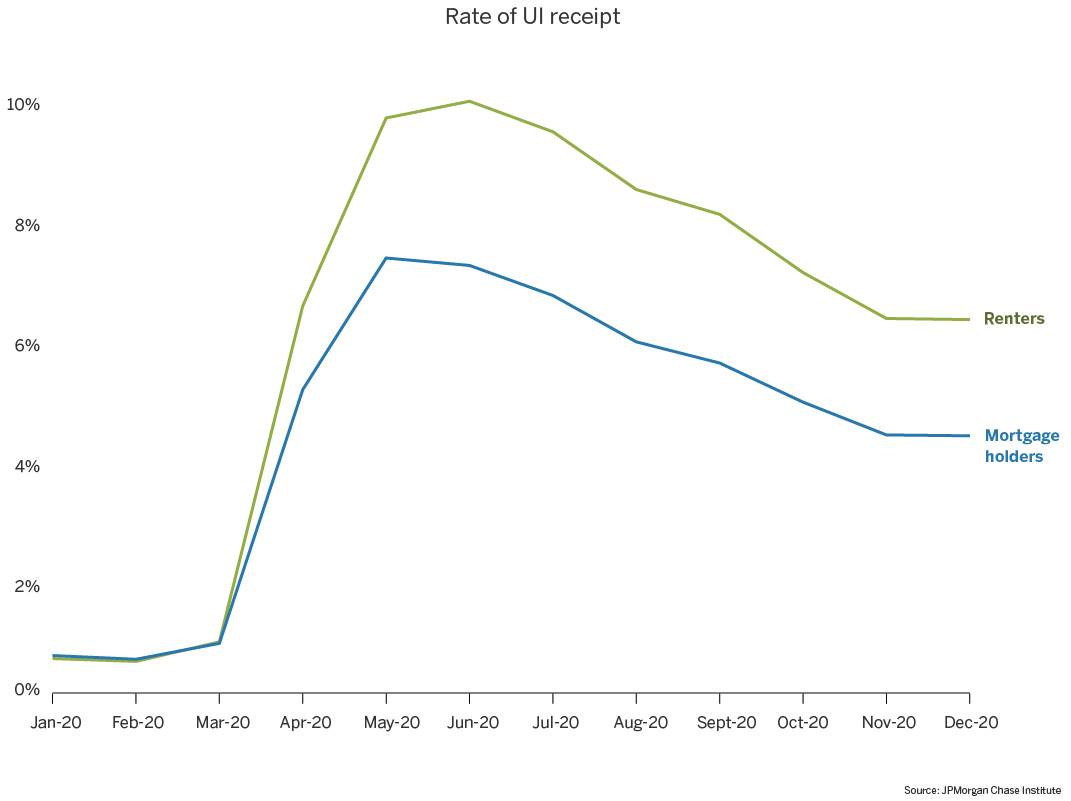

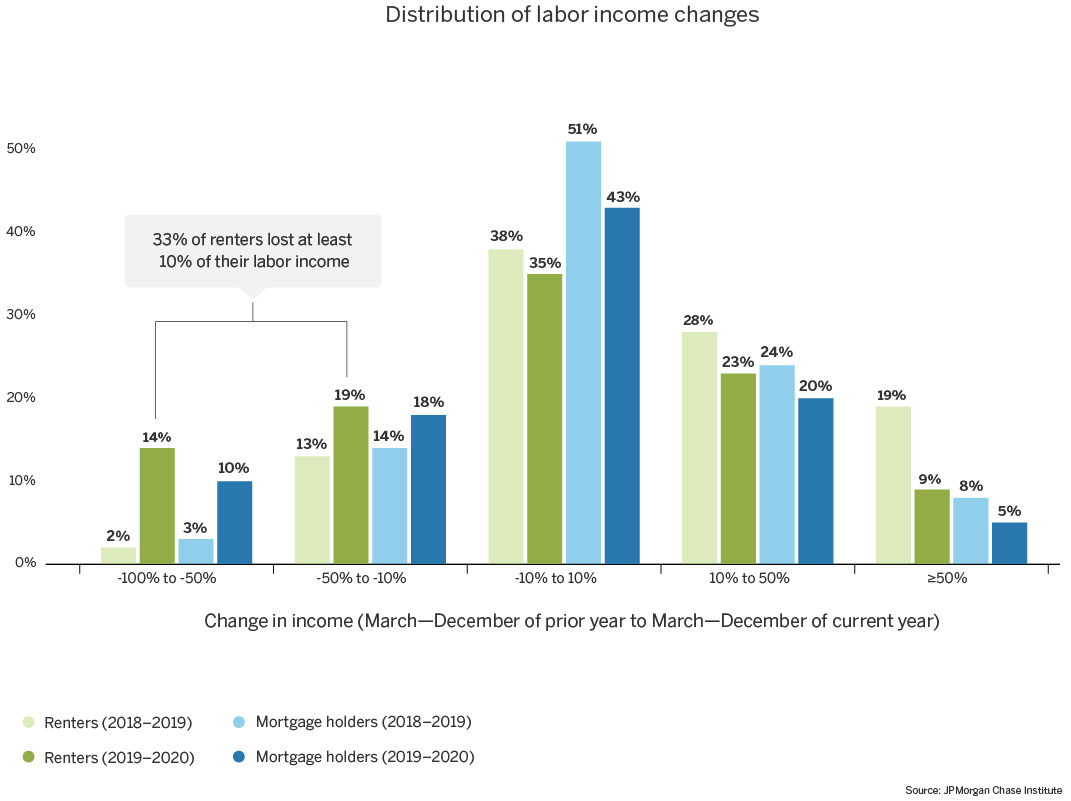

Compared to mortgage holders, renters were on weaker financial footing prior to the pandemic and experienced greater job losses and labor income declines during the pandemic.

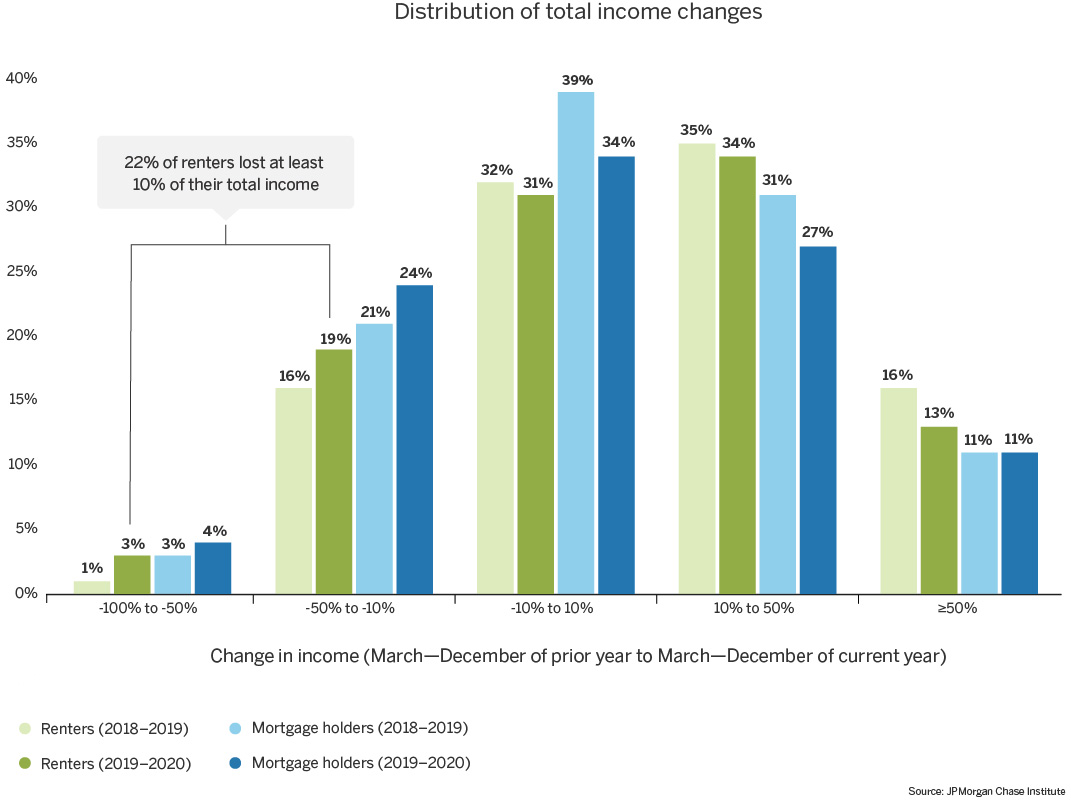

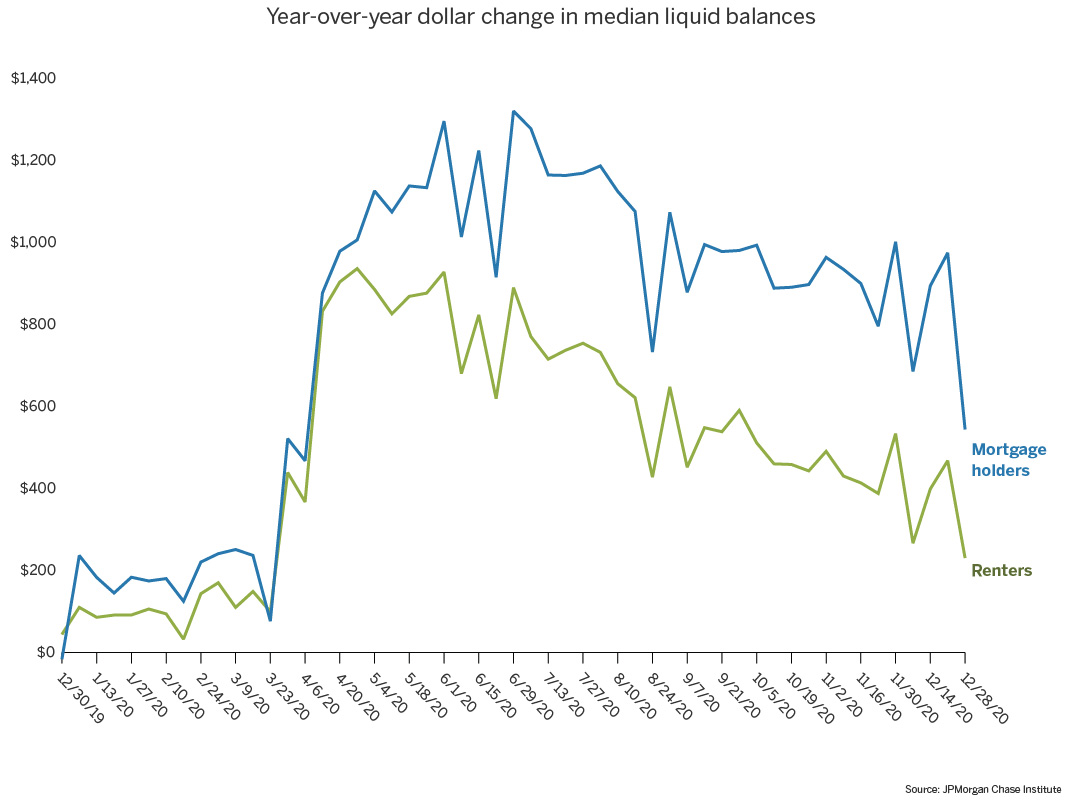

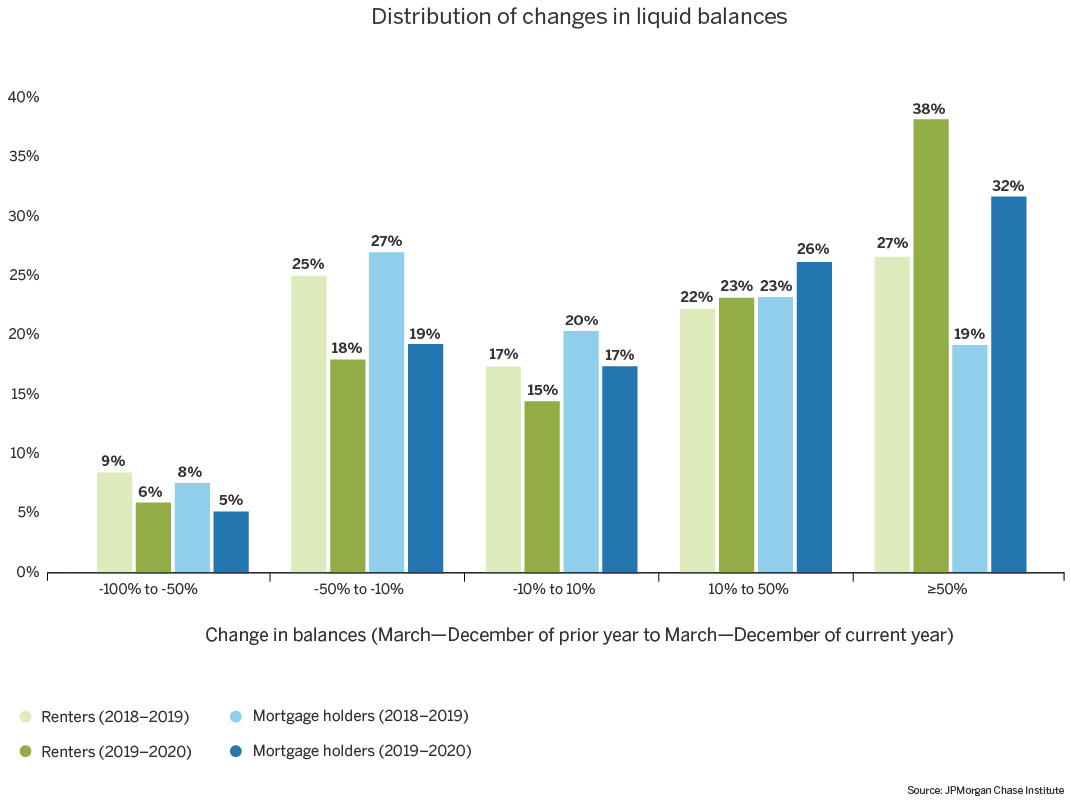

Government statistics suggest that renters were more likely to have suffered financially during COVID because of the industries in which they are concentrated. Our data on UI receipt suggests that renters did in fact experience more job loss and our income data show that renters were more likely to have suffered major loss of labor income relative to mortgage holders and relative to their own income patterns pre-COVID. Even though generous expansions of UI and EIP checks increased total income for many renters, more than one in five saw their total income decrease by more than 10 percent. Finally, renters entered the pandemic with much lower levels of savings and their relative position did not improve meaningfully during the pandemic despite government stimulus programs as they depleted more of the stimulus-generated additional savings by the end of the year than mortgage holders. Importantly, our results should be interpreted with the caveat that these results likely represent a “best case scenario” for renters since our sample of renters skew higher in income and the gap between renters and mortgage holders in our sample is smaller than exists for the general population. An analysis that includes more low-income renters than our data can currently reach—especially those that are underbanked or already struggling with housing payments—would likely show worse financial outcomes for renters.

These results point to renters needing more government support than they received in 2020, which they are on track to receive with the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, so it will be important to continue monitoring the financial outcomes of renters in the coming months.

While government support in the form of expanded UI and EIP checks generally boosted total income and savings, a significant fraction of renters still suffered moderate to severe losses in total income and savings. These renters may have not qualified for UI because they lost income but did not lose their jobs or, for some higher-income renters, UI may not have replaced all of their income.

A similar fraction of mortgage holders also suffered similar total income and savings losses. Yet these mortgage holders who needed help beyond UI and EIP largely had access to a year of mortgage forbearance while there was no such widely available and easily accessible program for renters until the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 passed in December 2020, which established a $25 billion Federal Emergency Rental Assistance Program for state and local governments.

Moreover, lenders made it easy for homeowners to opt into mortgage forbearance, while renters faced red tape when accessing rental assistance programs and landlords eager to find paying tenants. Having learned from the Great Recession and various forbearance programs enacted for natural disasters, policymakers and mortgage servicers made it nearly frictionless for mortgage holders to ask for forbearance with proactive outreach efforts and no documentation requirements. Related JPMC Institute research (Farrell et al, 2020) shows that the CARES Act mortgage forbearance program helped homeowners in need during the pandemic with little evidence of widespread moral hazard despite the lack of documentation requirements. On the other hand, while some landlords undoubtedly passed on the relief they received to their renters and others worked out flexible payment plans with renters on an individual basis, generally speaking they had greater incentive, when the patchwork of eviction moratoria allowed, to evict tenants that were unable to pay in the hopes of finding one that could. And in order to apply for the Emergency Rental Assistance Program, renters needed to fill out forms and upload documents proving unemployment or income loss, risk of homelessness or housing instability, and income that did not exceed 80 percent of area median income (AMI)., ,

Providing renters with more financial support could take many forms.

The need for rent relief may well exceed the $25 billion available for the Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which the expected passage of the American Rescue Plan Act would help to address. Our results suggest potentially significant financial need among renters beyond UI and stimulus checks. Other studies have estimated that back rent may add up to somewhere in the range of $34 to $70 billion., , And the Census Pulse Survey for January 2021 provides evidence of ongoing housing insecurity with 18 percent of households indicating they are behind on rent, 13 percent having no confidence that they will be able to pay rent next month, and 14 percent reporting that they are very likely to be evicted in the next two months., Furthermore, the Emergency Rental Assistance program is only available to families making less than 80 percent of AMI and our results show that even higher-income renters captured by our data exhibited significant financial need during COVID. What can be done about this? The design of additional assistance programs to address the needs of renters ought to take into the following considerations:

- Effective and administratively feasible targeting: Assistance needs to strike a balance between targeting renters most in need and making assistance easily accessible. Our data show that renters had less stable labor income, both pre-COVID and during the pandemic. Expanding eligibility for UI post-COVID and identifying additional ways, beyond UI, to deliver relief to families who have experienced income losses may provide relief to a wider range of workers, many of whom may be renters. These could include temporary expansions in other means-tested safety net programs, including cash assistance (TANF), in-kind supports (e.g. SNAP and Medicaid), and tax credits (e.g. EITC and Child Tax Credits).

- The solvency of landlords: Though popular, government mandated rent “cancellation” or forbearance programs are difficult to implement given the highly fragmented and less capitalized market of landlords. In contrast, the federal government insures a large share of mortgages and imposes capital requirements on financial institutions engaged in home lending. Additionally, mortgage holders are expected to eventually catch up on their payments over the course, or at the end, of their loans. Proposals to provide rental assistance or forbearance need to address the downstream impacts on landlords. This is also true for extended eviction moratoria as, without eviction as an option, landlords cannot recoup rent on their units. Of course, if landlords have opted into forbearance, as 12 percent have, they should be required to pass on some of the protection to their renters.

- Macroeconomic impacts: Well designed, targeted assistance programs could act as a form of economic stabilizer by enabling renters to maintain their level of consumption. On the other hand, there could be potential macroeconomic effects of dramatic increases in government spending, including the risk of rising inflation.

- Availability of affordable housing: Even before COVID, the United States was facing a severe affordable housing crisis with many households experiencing high degrees of housing insecurity. Efforts to increase the supply of affordable housing could address current and future needs for rental assistance.

- Ways to support the financial health of renters more generally: Previous JPMCI research examined income volatility and the potential role for policymakers and businesses to help families smooth their income (Farrell et al, 2019). One possibility is taking advantage of months with income spikes to save for a rainy day fund via deductions for benefits, tax withholdings, and pre-tax savings accounts rather than setting aside a constant fraction each month. Also, policymakers could consider the possible benefits of providing access to tax withholdings during the year or distributing tax refunds or the Earned Income Tax Credit periodically throughout the year.

In conclusion, supporting the financial health of renters both during and after COVID would promote greater housing security and economic resilience of lower-income families and their landlords.