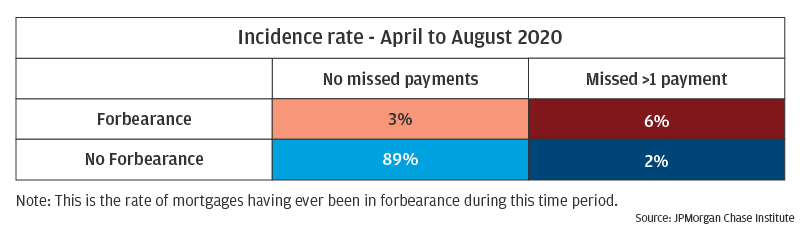

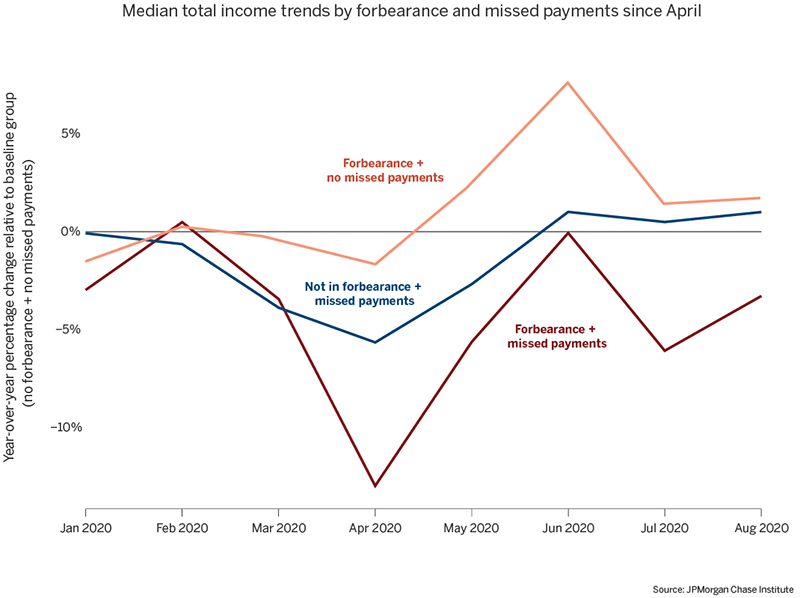

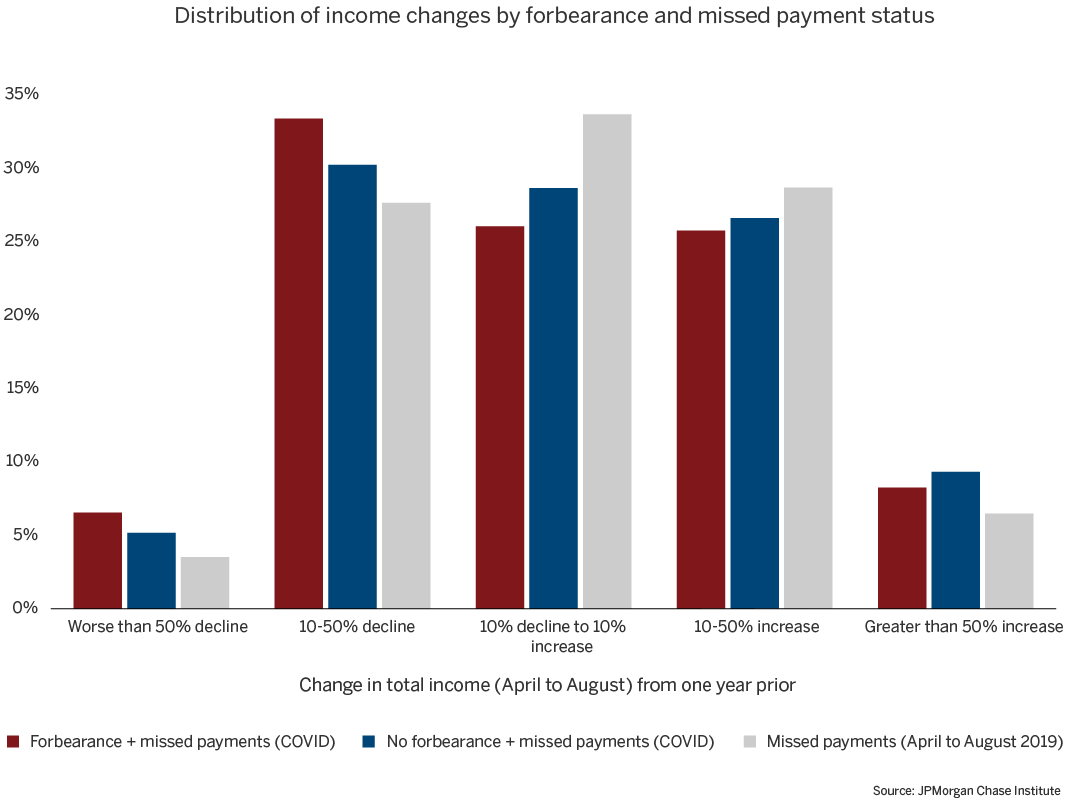

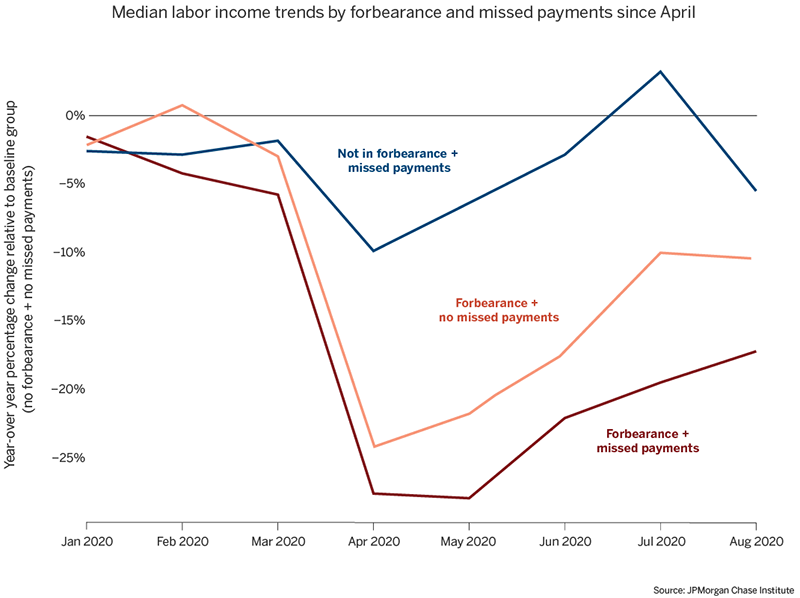

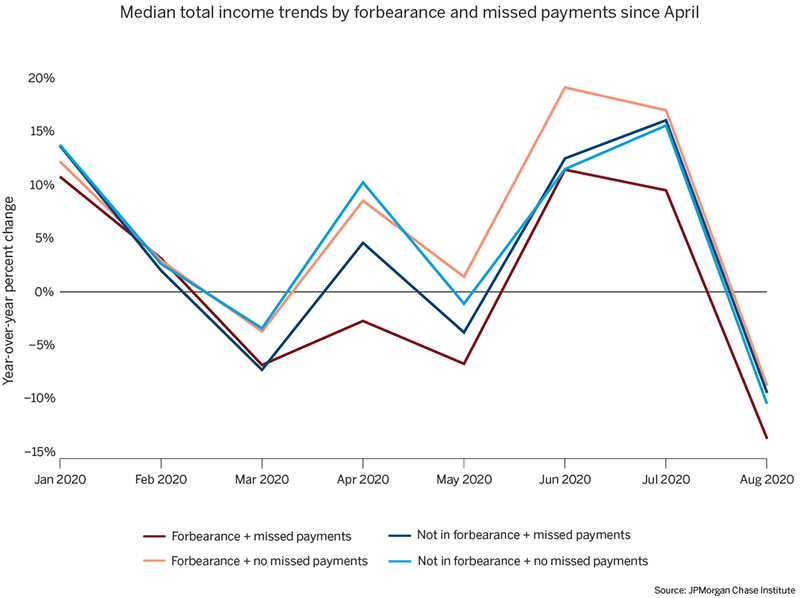

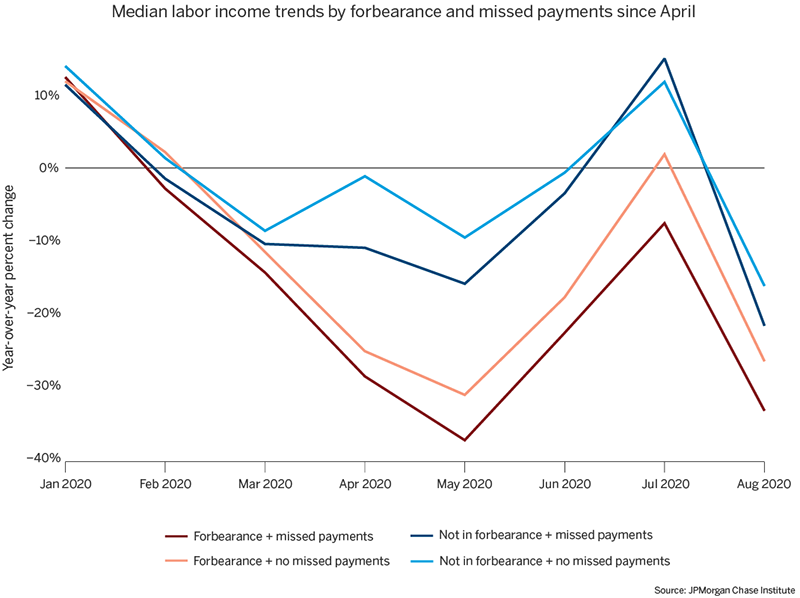

Mortgage forbearance has been an important form of relief uniquely offered in this COVID-induced recession. Roughly one in eleven homeowners have taken advantage of mortgage forbearance as of August 2020, and yet a third of homeowners in forbearance made all payments to date. We also find little evidence of significant moral hazard, though we do see evidence that the small number of homeowners who went delinquent without forbearance were experiencing financial hardship. Families using forbearance to miss mortgage payments had larger drops in income than other homeowners and experienced income changes similar to those who became delinquent without the protection of forbearance. In addition, families in forbearance were more likely to have lost labor income and received unemployment benefits than families not in forbearance. Finally, we find that forbearance helped families with low cash buffers to maintain that cushion.

CARES Act mortgage forbearance policies helped homeowners experiencing financial hardship in a material way.

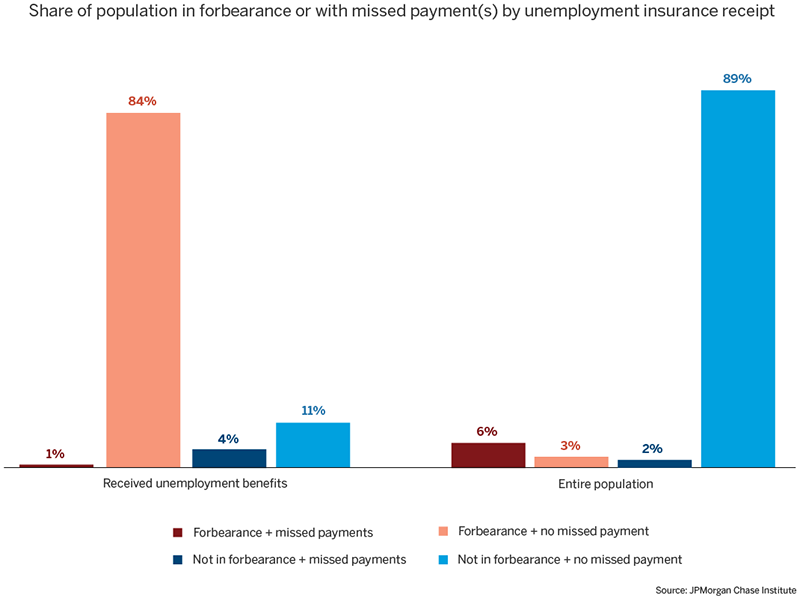

Families who experienced large income declines or lost a job and received UI disproportionately took advantage of forbearance whether as a precautionary measure or to use it to miss payments. For homeowners who missed payments, forbearance allowed them to miss payments without a negative effect on their credit scores. Of course, this also has the downside of making it harder for financial institutions to identify risk using traditional credit scoring models.

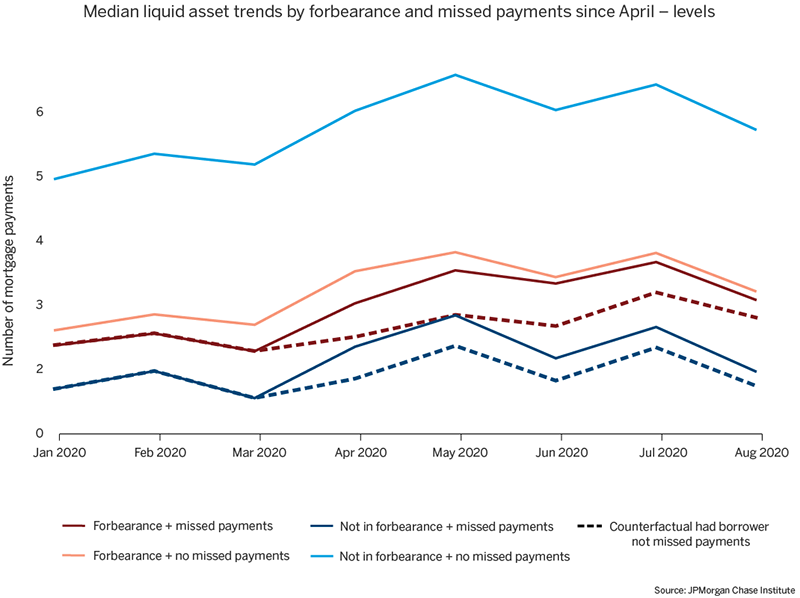

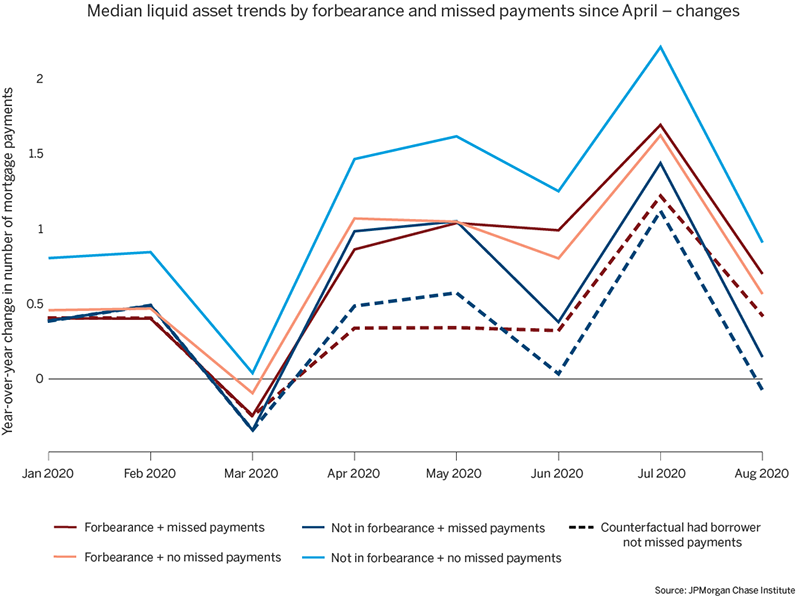

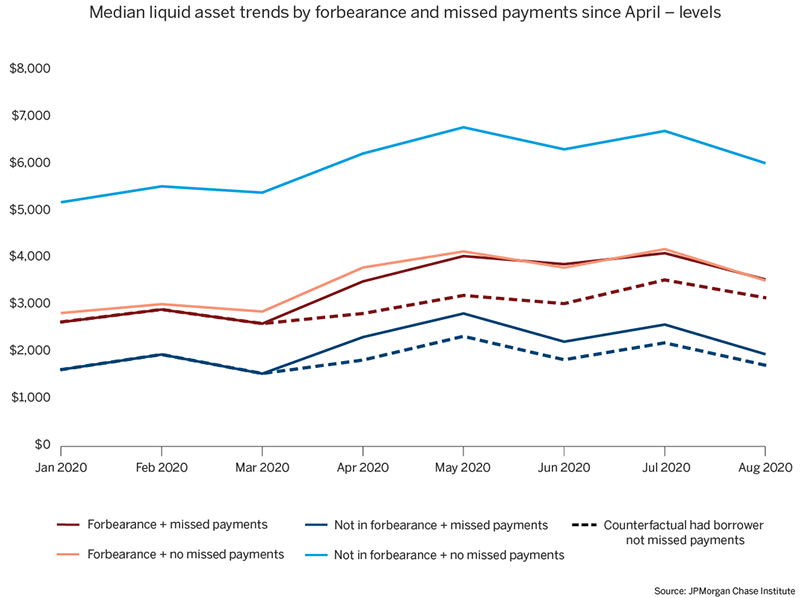

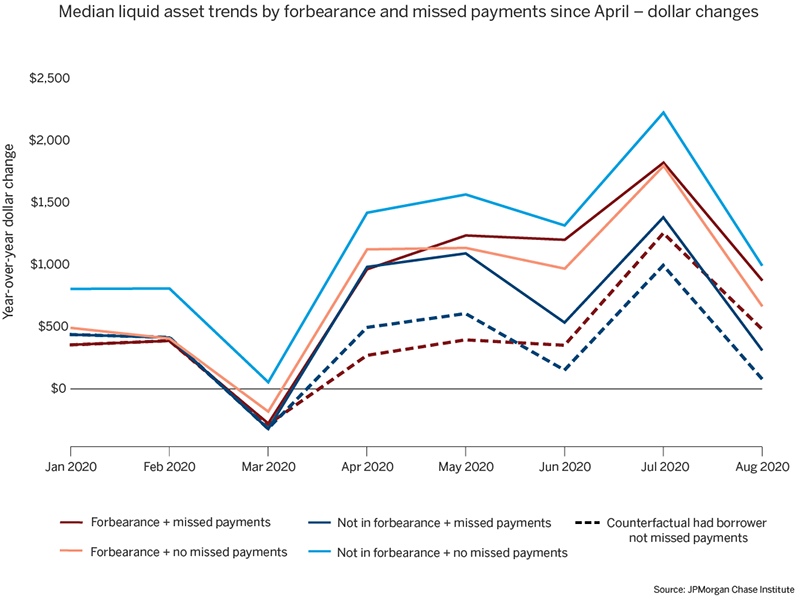

In addition, forbearance helped families to build up a cash buffer which may avert hardship should labor market conditions not improve as forbearance ends. The pandemic represents a large uncertainty shock to the economy–a policy that allows vulnerable families to conserve their resources has real benefits.

There is little evidence of material moral hazard as a result of mortgage forbearance so far.

The CARES Act offered immediate payment relief to all homeowners with federally-backed mortgages (which many servicers extended to all loans) while requiring only an attestation of COVID-related hardship. The lack of documentation seemingly introduced the potential for significant moral hazard. During the Great Recession, fear of widespread fraud and abuse drove the decision to require documentation for government relief programs. However, we see little evidence of significant moral hazard in our data so far.

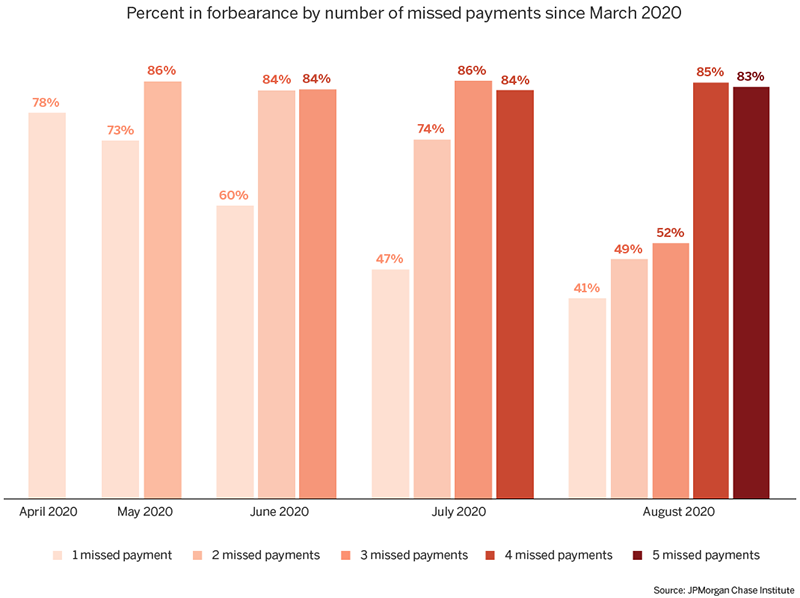

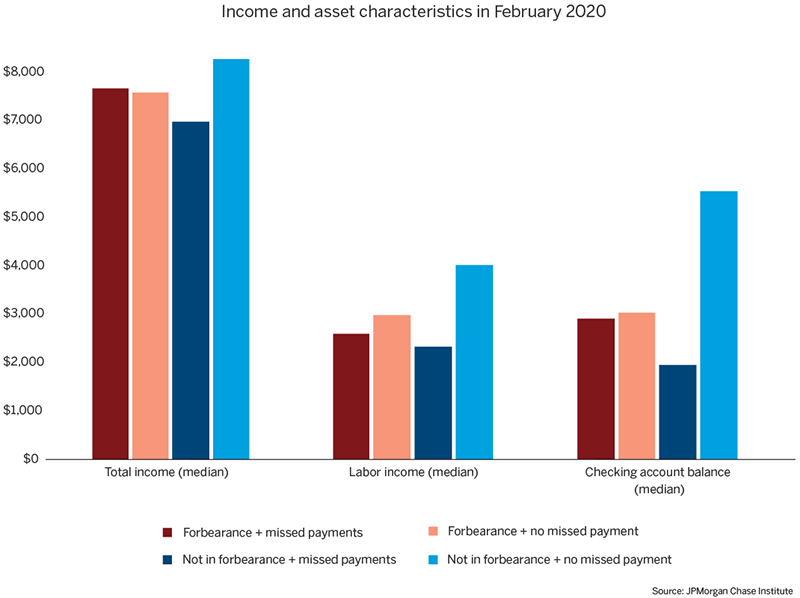

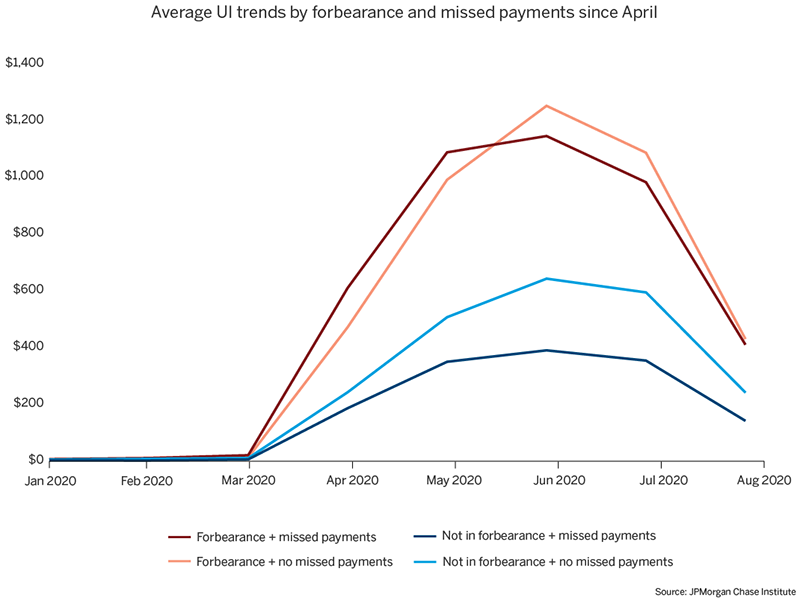

Importantly, while 9 percent of homeowners were in active forbearance at some point during the period we studied, only two thirds missed any payments. And our data show that this subset had the worst total income trends of any group. Furthermore, we show that homeowners who chose to opt into forbearance lost more labor income than those who did not and received more UI income. For those who received unemployment benefits, they overwhelmingly were in forbearance, but chose to continue making their mortgage payments, evidence that people paid when they could.

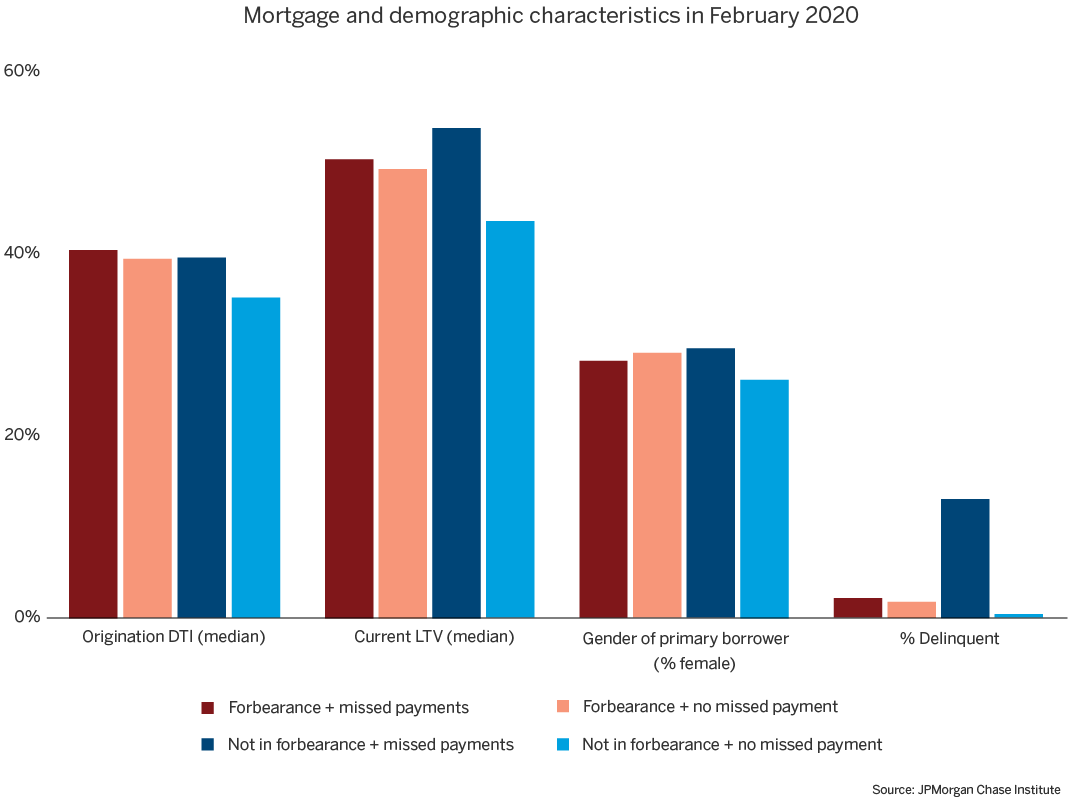

It is true that forbearance probably benefited homeowners who were already delinquent pre-COVID who could now go into forbearance when they would have probably become more delinquent over time anyways. However, our data show that baseline delinquency was very low for the groups in forbearance and was highest for those going delinquent without forbearance.

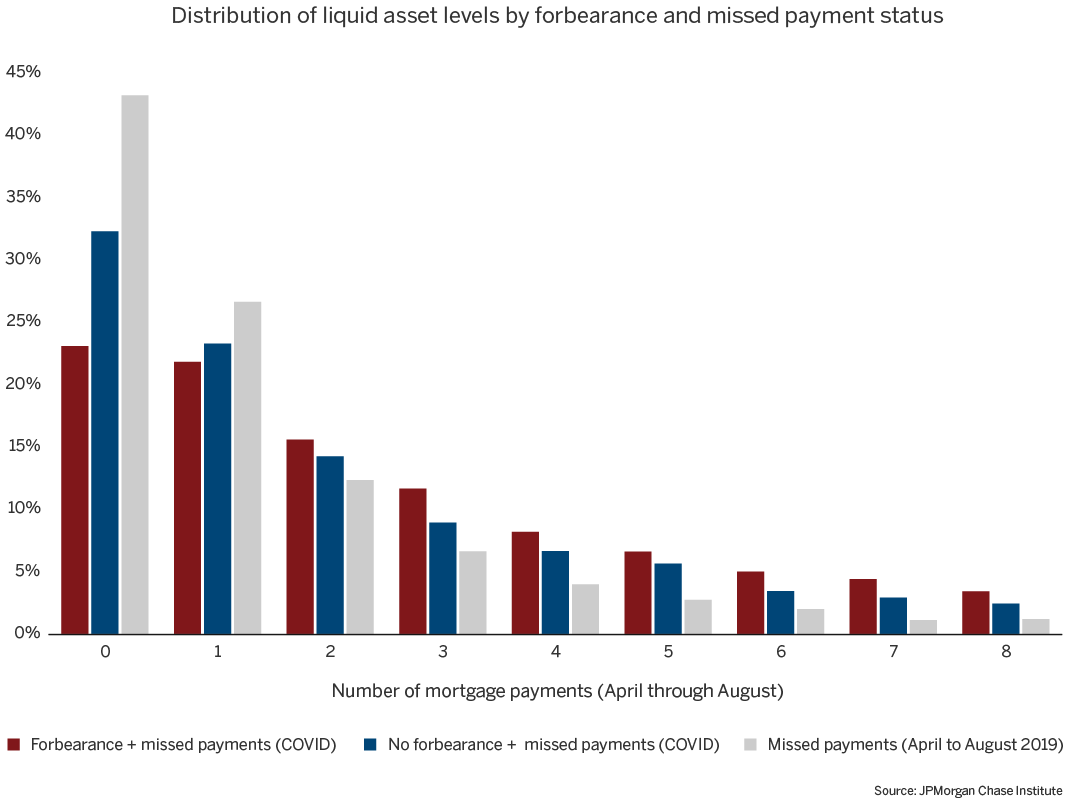

It is also true that homeowners who missed payments during COVID had larger cash buffers than those who were delinquent pre-COVID, and this was particularly the case for those missing payments in forbearance. However, liquid assets have grown for families as a result of the CARES Act government supports and COVID-related spending drops (Cox et al. 2020). And some homeowners may have chosen to forgo mortgage payments on a precautionary basis because they had the costless option to do during an otherwise highly uncertain time. This could be viewed as some degree of moral hazard, but allowing homeowners to maintain this small cash buffer likely allowed them to maintain consumption levels and meet other debt obligations. And it is almost inevitable that a policy like this would come with some small degree of moral hazard. However, that cost must be weighed against the benefit of helping many more homeowners than if the policy had required substantial documentation and paperwork. As evidence from the Great Recession shows, those requirements hampered the success of many of the housing relief programs from that period.

There is room for improvement in future legislation as a small fraction of homeowners facing hardship did not benefit from forbearance as defined under the CARES Act

Our results show that 2 percent of homeowners missed payments during COVID while not in forbearance, though 15 percent of them were delinquent prior to COVID. Black Knight data shows that over 1 million past due mortgages are not in forbearance (400,000 became newly delinquent post-COVID). Of these, 680,000 are federally-backed and 405,000 are FHA/VA loans.

Reducing this share could include changes on several fronts including patching some of the holes left by the CARES Act (e.g., non-federally backed mortgages and non-COVID related hardship), but according to survey evidence, the two main reasons for not entering forbearance when there is a need are (1) lack of knowledge around relief options and (2) worries about what happens when forbearance ends. , Government agencies and servicers spent significant resources on reaching homeowners in need to let them know their options, but despite these efforts, some homeowners may simply be difficult to reach.

While additional effort from community partners or others might make a difference, a change that might have had a larger impact would have been if the CARES Act had been clearer on forbearance exit policies. The CARES Act was silent on this and, importantly, did not specify whether homeowners would be on the hook to make a lump sum payment to cover all missed payments once the one-year forbearance period ended. While guidance from government agencies that balloon payments would not be required eventually came, by then, the media had already widely circulated stories that could have scared some homeowners from asking for forbearance.

Was widespread, easily obtainable mortgage forbearance the right policy?

In summary, we see evidence that mortgage forbearance helped families facing financial difficulty during a sudden and severe economic contraction get immediate payment relief. We do not see evidence of widespread moral hazard. The CARES Act forbearance policies, therefore, appear so far to have been a large step in the right direction relative to policies during the Great Recession.

However, homeowners are generally higher-income while this recession disproportionately affected lower-income families and families of color, who are more likely to be renters. In a world with scarce resources, was mortgage forbearance the right policy tool? Certainly, given the nature of this recession, policies targeted at the most vulnerable families (such as expanded unemployment benefits) and businesses (such as the Paycheck Protection Program), were critical to the success of the CARES Act. The durability of the housing market and the forbearance results in this report are likely the result of not just the mortgage forbearance policies, but these other programs included in the CARES Act and deployed over the same period. With the expiration of the $600 unemployment supplement at the end of the July and the exhaustion of the subsequent Lost Wages Assistance, many jobless workers may see a drop in their income if they are unable to return to work. In this circumstance, jobless workers may face a choice to cut spending or fall behind on debt payments, including their mortgage. As a result of mortgage forbearance, deferring mortgage payments is a costless option that, under current law, is available to them for a year after they opt in.

Finally, the success of the mortgage forbearance policies themselves will depend critically on the results of exit options. Exit options will vary for different homeowners depending on who owns their loan, who services the loan, and their own financial circumstances at the end of the forbearance period. However, given the depth of the recession, many homeowners may need additional help.

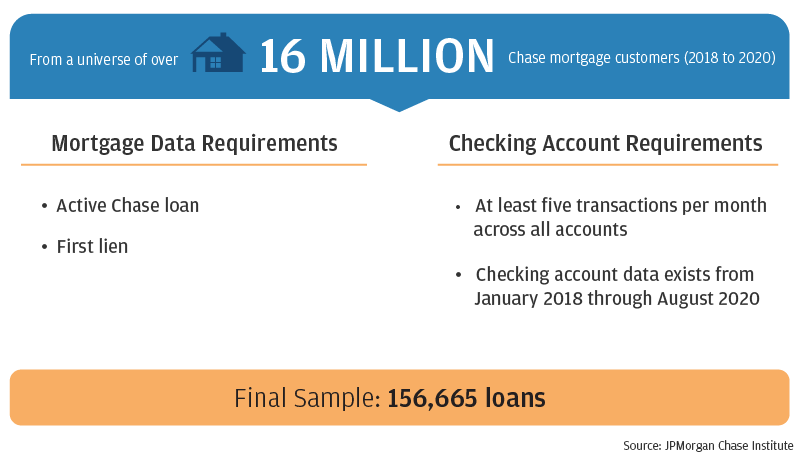

Data Asset and Methodology

For this report, the JPMorgan Chase Institute assembled a de-identified data asset of Chase customers to measure income and liquid asset trends during COVID. In conducting this research, we went to great lengths to ensure the privacy of customer data.