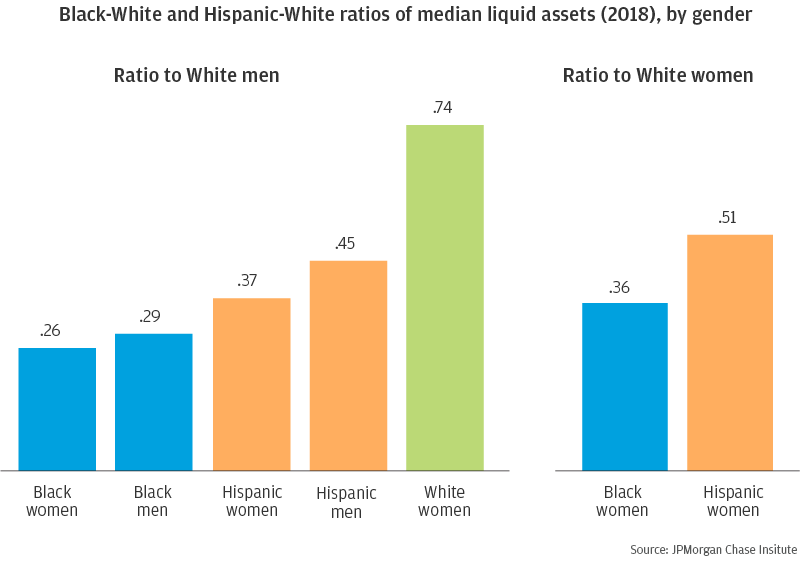

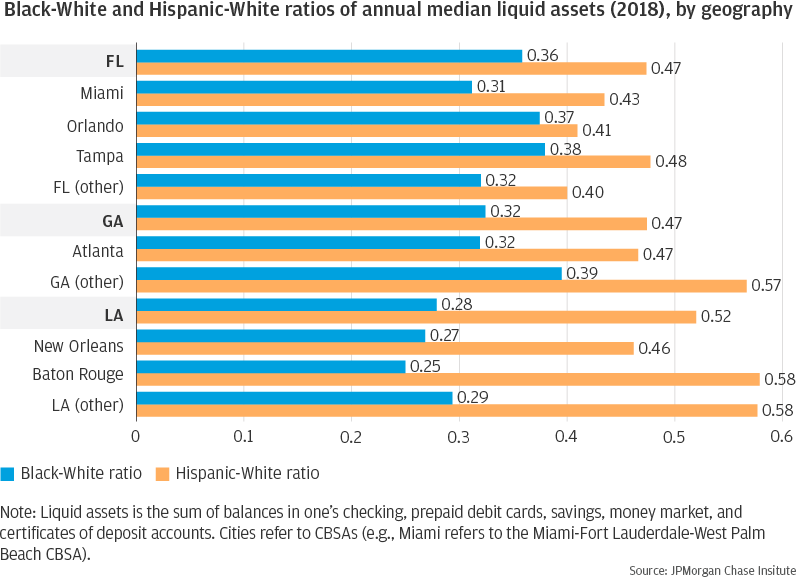

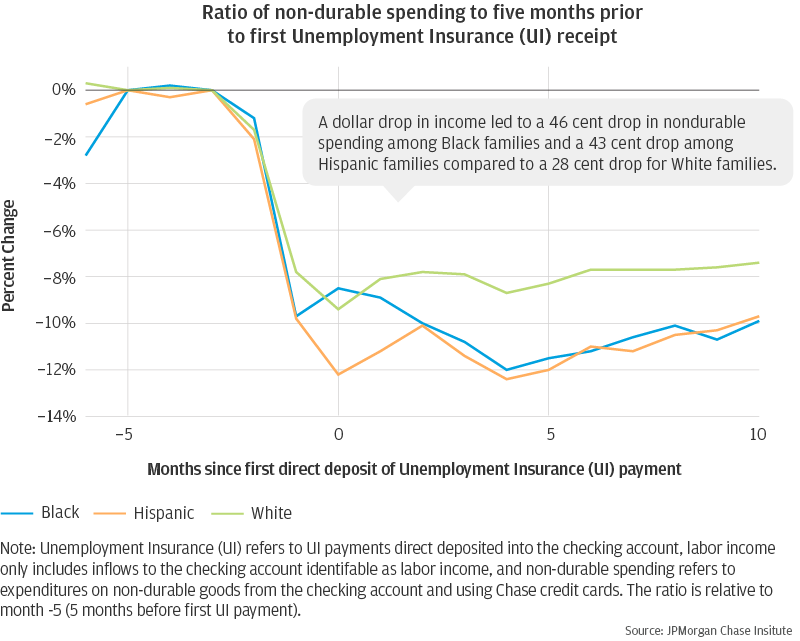

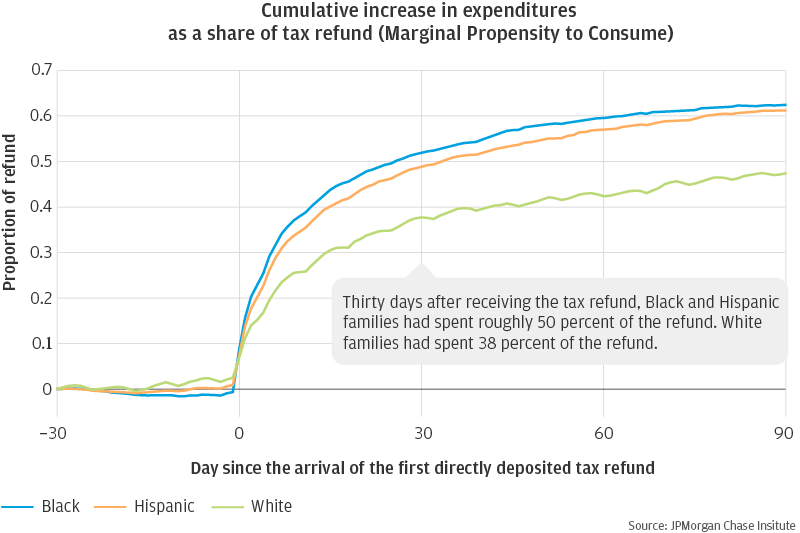

In conclusion, we find large racial gaps in take-home income and liquid assets which persist across age, income, gender, and geography. The racial gap in liquid assets makes Black and Hispanic families more vulnerable to income fluctuations. Families with lower liquid asset buffers—disproportionately Black and Hispanic families—cut their consumption to a greater extent when they experience involuntary job loss and increase their consumption to a greater extent when they receive a tax refund. However, racial gaps in consumption smoothing disappear when we account for the racial gaps in liquid and financial asset buffers.

These findings have important implications for public policy and the distributional impacts of policy interventions. They raise broader questions about how to reduce financial volatility and increase liquid assets for low-income families and, importantly, address the structural factors that contribute to racial gaps in income and assets.

Efforts to reduce income volatility, particularly among low-income families, may include expanding unemployment insurance benefits and ensuring access to workplace benefits and protections such as paid sick and family leave and a predictable work schedule. They could also include distributing tax credits and withholdings throughout the tax year.

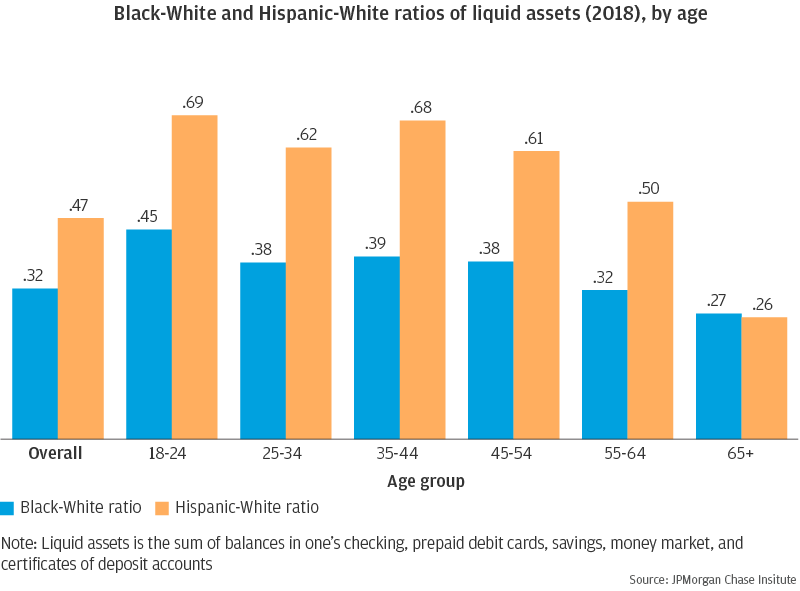

In addition, we must consider ways to help families manage financial volatility. We estimate that a liquid asset buffer of roughly $5,000 to $6,000—as a form of “private insurance”—might enable Black and Hispanic families to sustain their typical consumption levels through a job loss or major cash-flow event. This is considerably more than the $1,000 to $1,500 that the median Black and Hispanic family in our sample currently has. Thus, a key question is how to support families in building these liquid assets.

Policies and programs that boost income and address the underlying challenges Black and Hispanic families face within the labor market could help to close racial gaps in income in the short-run. These could include increasing the minimum wage, strengthening the Earned Income Tax Credit, investing in job training programs, and reducing the barriers to employment for individuals with criminal backgrounds.

To close the racial gap in liquid assets, which is much larger, we also need stronger programs, policies, and innovations to both reduce expenses that disproportionately burden Black and Hispanic families and promote asset building among low-income families. These might include efforts to make housing, high-quality childcare, and higher education more affordable as well as employer- and government-sponsored supports for asset building.

The private, nonprofit, and government sectors all have important roles to play as policymakers, service providers, and employers in closing racial gaps in income and wealth. Our research shows the importance of disaggregating economic and financial statistics by race and measuring these statistics at a high frequency. Doing so can help shed light on the factors that contribute to racial differences in financial outcomes and instruct us on how to design more efficient and equitable policies.