The rise in inflation since mid-2021 to multi-decade highs presents a worrying trend for households’ financial health, particularly if nominal incomes, or non-inflation adjusted income, of financially vulnerable families lag behind prices. Policymakers have noted that lower income households are more vulnerable to increases in consumer prices given their higher share of spending on necessities. While elevated cash balances during COVID have provided a cushion for spending, savings stockpiles have declined from their peaks, implying sustained consumption at recent levels will soon require higher real incomes or further liquidity drawdowns. This raises important questions as to how households have been coping. Have nominal incomes kept pace with inflation to allow households to maintain their purchasing power? What types of households are doing better or worse?

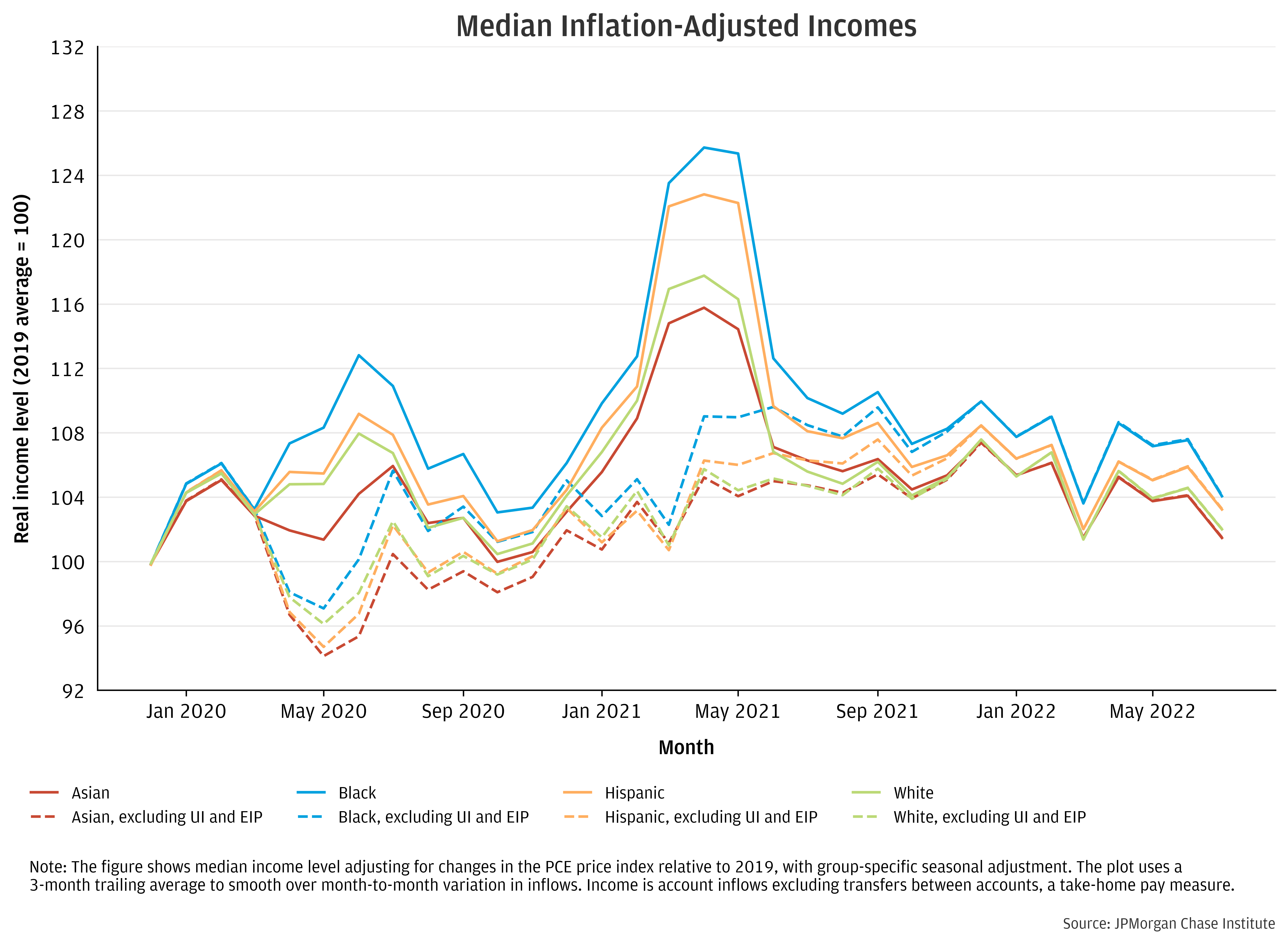

We use de-identified data covering 10 million households’ account inflows to answer these questions—tracing the trajectory of income growth, adjusting for changes in the price level, over the period since the pandemic began. We build on prior Institute reports that looked at income growth over the business cycle and during COVID, highlighting differences across the income spectrum and racial groups. We also track incomes both including and excluding Unemployment Insurance (UI) and Economic Impact Payments (EIP) to highlight the role of government programs in supporting incomes during the pandemic.

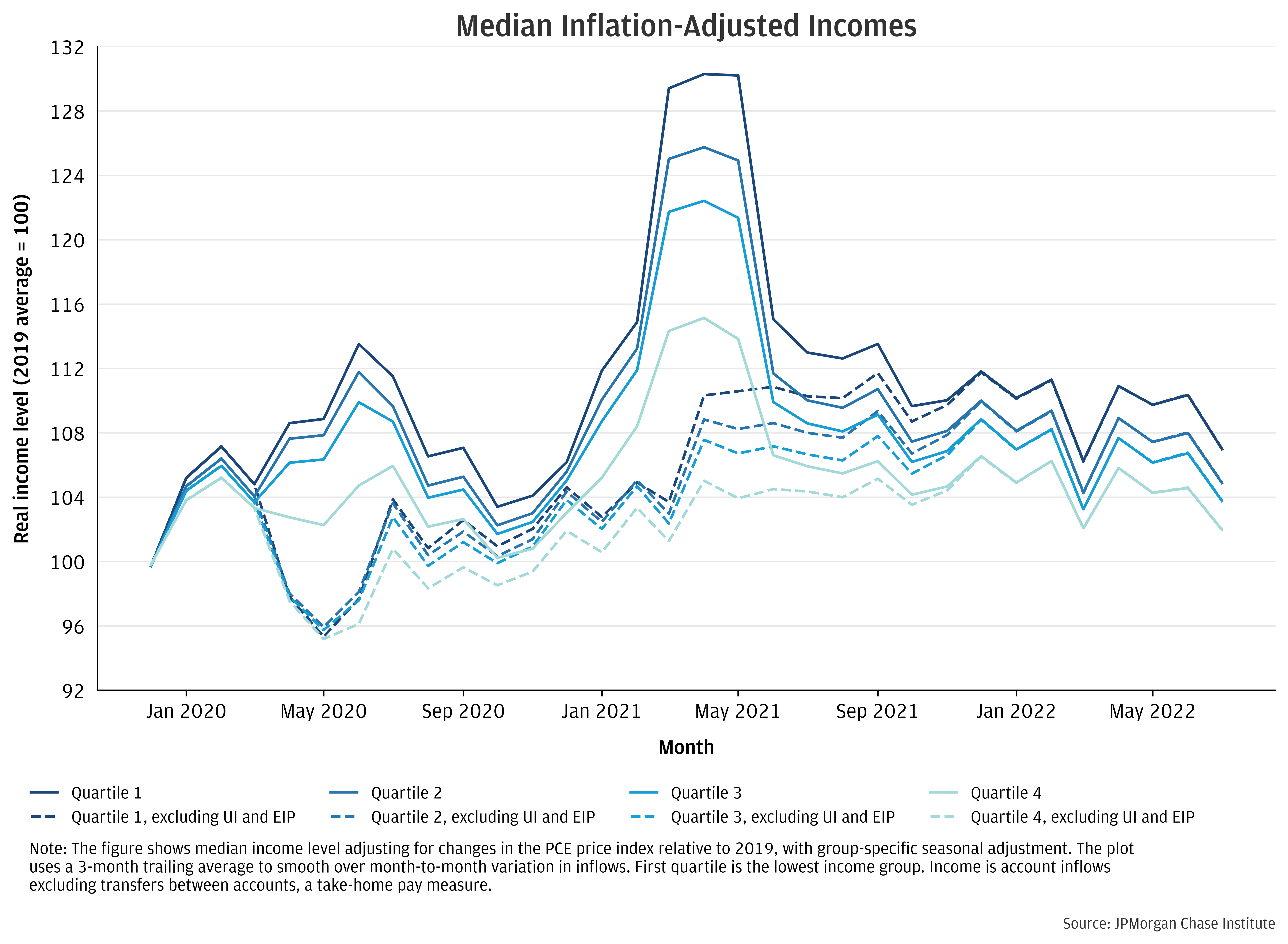

Figure 1 below shows how median real incomes have evolved across income groups from January 2020 through July 2022, measuring each person’s inflation-adjusted income relative to their 2019 average. We normalize the data by removing a group- and month-specific effect, using seasonality observed in 2018 and 2019. All income quartiles have higher real incomes in 2022 than in 2019. Individuals in the lowest income quartile—based on average incomes in their ZIP code—have experienced the largest relative gains, comparing 2022 earnings to 2019. However, the trend in real incomes since 2021 have been modestly downward across income groups, as elevated inflation reduced purchasing power. Moreover, growth in earnings implied here is biased upward relative to economy-wide aggregates, because of individuals’ aging over the sample window (see Box for details).