Model

To estimate the effects of advanced CTC payments on consumption, we use a difference-in-differences research design. It is important to note, however, that this case is imperfectly structured for a traditional difference-in-differences analysis because we know that our two groups—recipients and non-recipients of advanced CTC payments—differ in other ways besides their CTC recipiency alone. In an ideal difference-in-differences design, pre- and post-policy outcomes for a treated group are compared to pre- and post-policy outcomes of a reference group that was not affected by the policy intervention but is otherwise similar to the treatment group (e.g. households on one side of a state border versus those just on the other side of the border). If the treatment and control groups are identical in all ways except for their receipt in treatment, then the control group may provide a credible counterfactual for the treatment group; that is, the treatment group likely would have behaved like the control group had they not been treated. In our case, implementation of the advanced CTC payments was nation-wide and affected all qualifying households that did not proactively opt out. This means that our “treatment” group of CTC recipients is comprised only of households that have dependent children, whereas our “control” group of non-recipients is comprised of households with none. In other words, our two comparison groups will be fundamentally different beyond the policy intervention and these differences in characteristics may lead to differences in behavior over time and the control group’s behavior may not be a counterfactual for the treatment group’s behavior. For this reason, we do not refer to these groups as “treatment” and “control” in this report.

We have made efforts to understand and quantify differences between recipient and non-recipient households and to account for those analytically wherever possible. Specifically, we include weights in our regression based on several key differentiating characteristics between the groups (details below). However, this is not sufficient to entirely remove differences between CTC recipients and non-recipients for a clear view of consumption differences that holds all else constant. Behavioral changes over time—which differ by group—create challenges to understanding consumption differences between recipients and non-recipients. (See detailed discussion and additional assessments in the box on Differing Trends by CTC Recipiency.)

Regression specification: We run regressions of the following form:

yit=αi+δt+βτCTCi1τ+εit

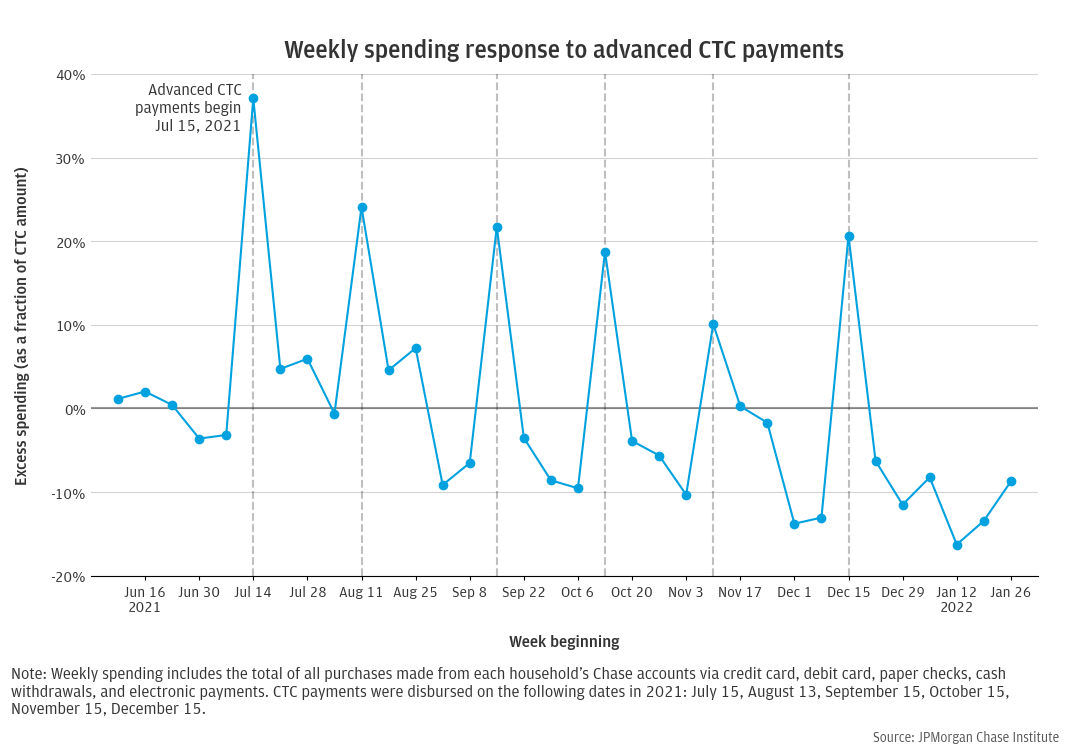

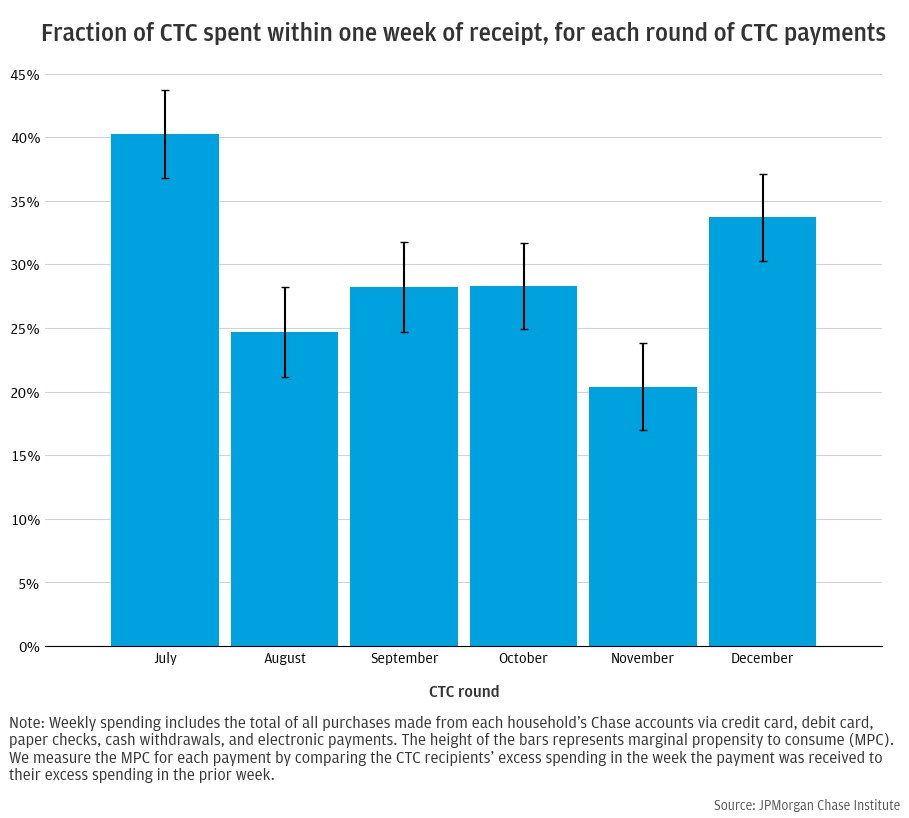

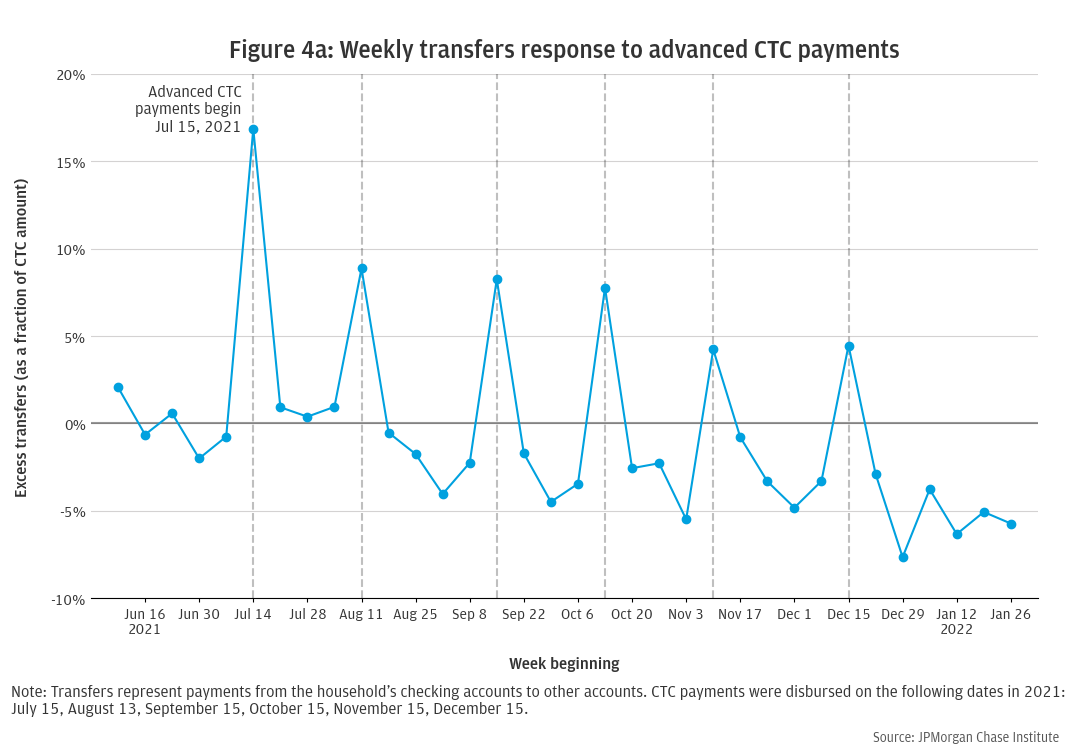

The dependent variable of interest for household i in week t is yit. See below for a full list of the dependent variables used in our analysis. Individual level fixed effects (αi) are at the household level, while time fixed effects (δt) are at the weekly frequency. CTCi represents the advanced CTC payment amount for household i. As noted in the Data Asset section, we remove from our sample the rare households that had inconsistent CTC payment amounts, therefore this CTCi is consistent at the household level across all six months of advanced payments. 1τ is an indicator (or dummy) variable for week τ where τ is only distinguished from t because t indexes all weeks in the sample while τ only includes weeks from June 9 and onward. (See Week variables below for additional discussion.) Weeks before June 9 establish the baseline difference between recipients and non-recipients. Thus, the βτ coefficients capture the change in the average difference in yit between CTC recipients and non-recipients in week τ relative to the difference in the baseline period. Furthermore, because CTCi is the dollar amount of CTC received, the unit of measurement of βτ is CTC amount itself; that is, βτ is the excess spending done by recipient households relative to non-recipients expressed as a fraction of the CTC payment the household received. Finally, εit represents the error term.

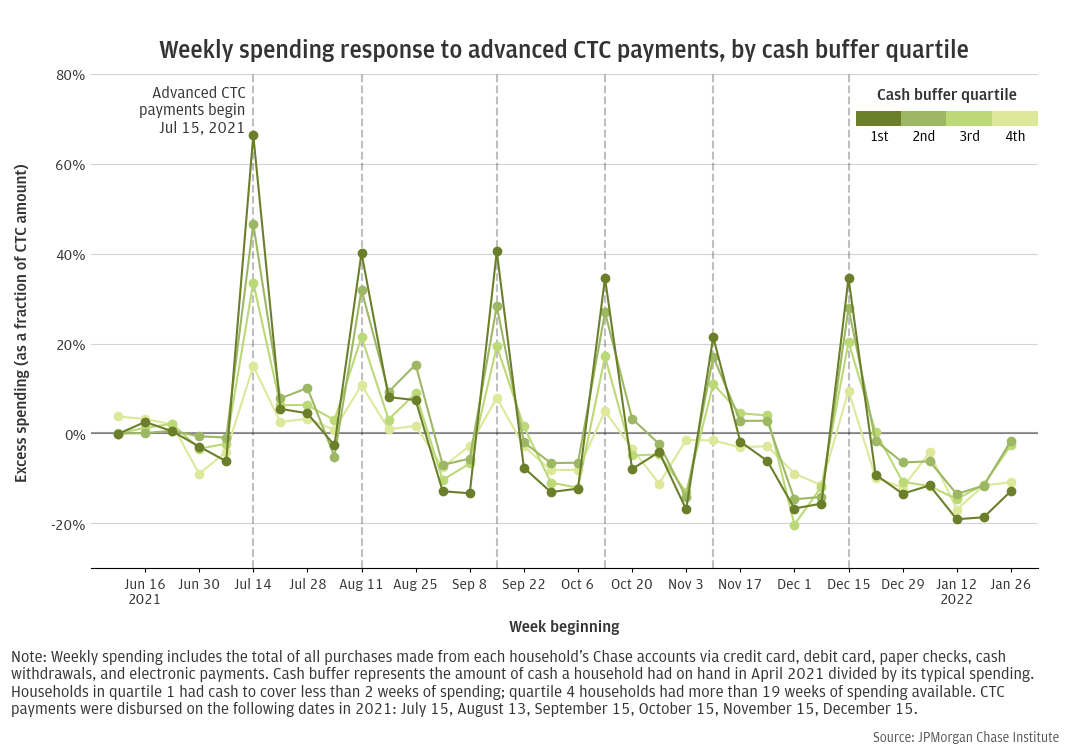

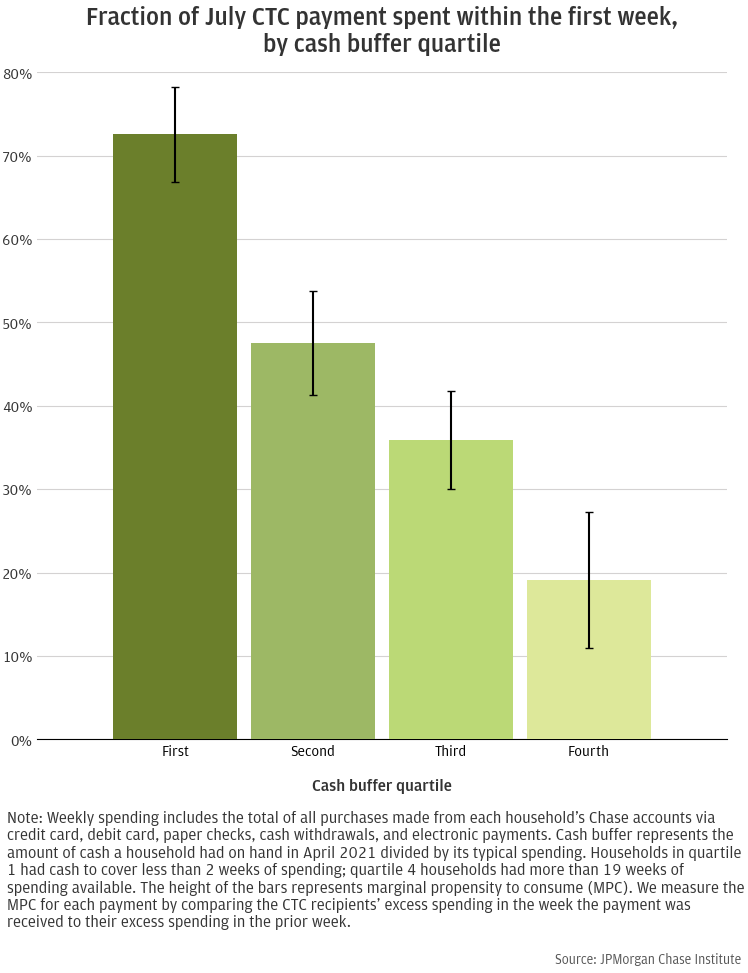

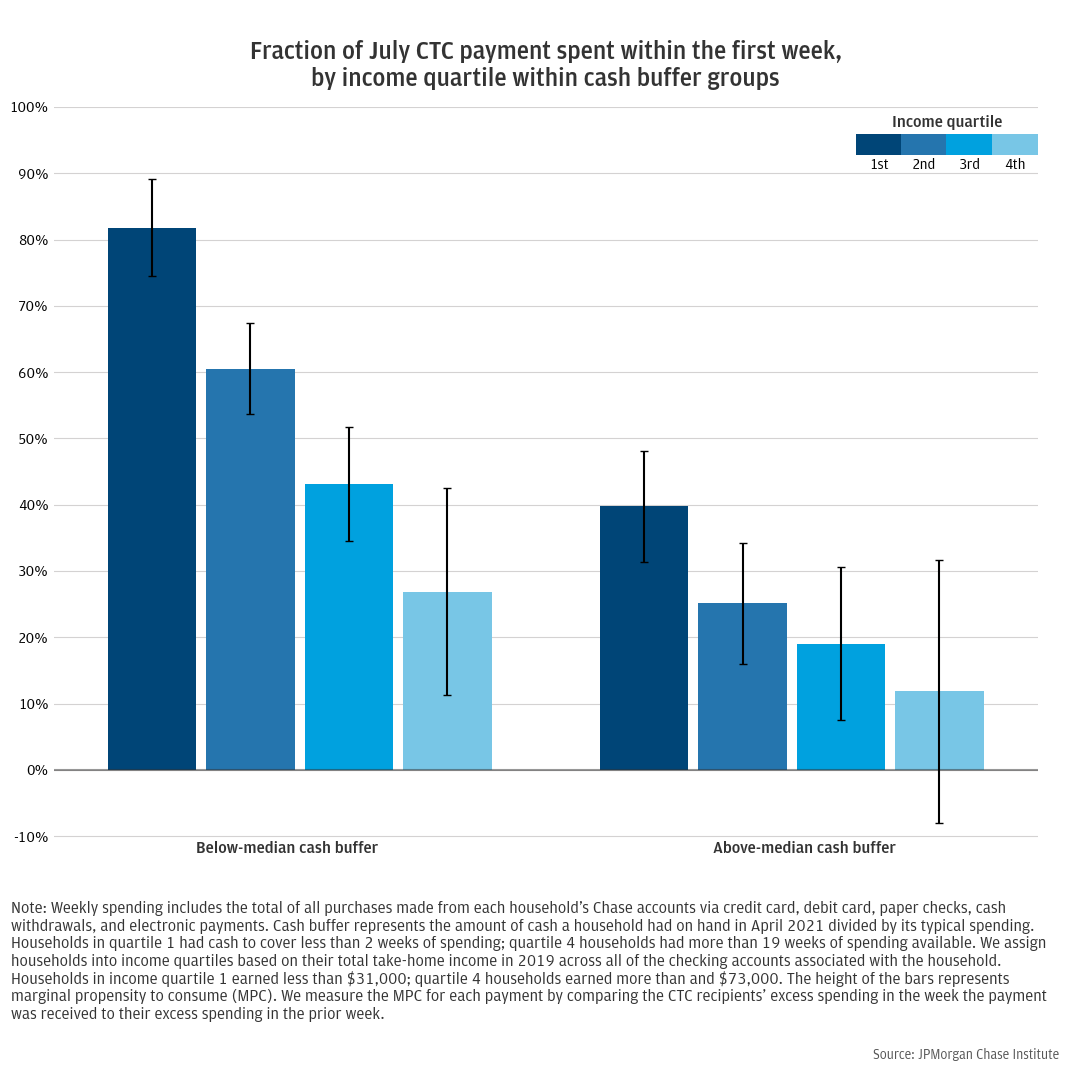

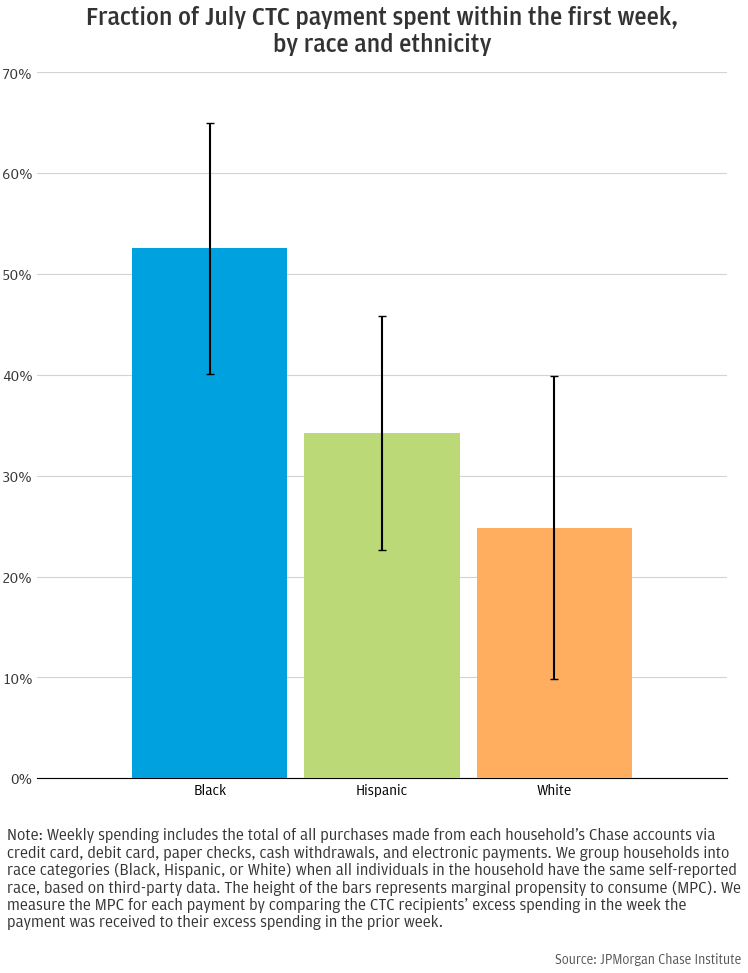

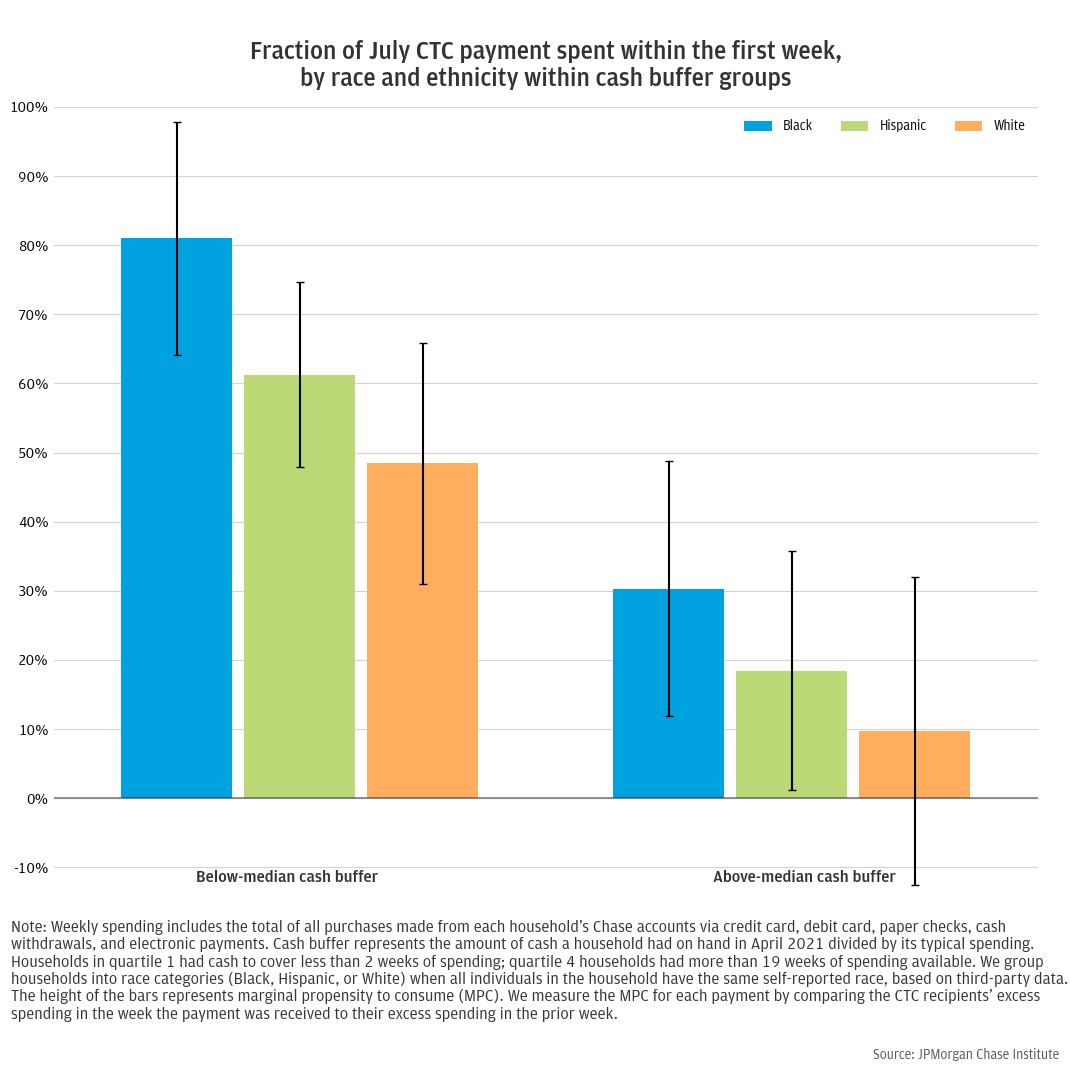

We also estimate similar specifications where the β and δ coefficients are allowed to vary by liquidity, income, and race groups, which allows us to measure separate CTC responses for each of these groups.

As discussed below, we use analytic weights in each regression to account for underlying differences in household characteristics between CTC recipients and non-recipients. We also cluster standard errors at the household level.

Dependent variables: To assess a complete picture of household consumption, we study several dependent variables.

- Total spending: This metric includes the total of all purchases made from each household’s Chase accounts via credit card, debit card, paper checks, cash withdrawals, and electronic payments.

- Spending sub-categories: To understand details of the spending response to advanced CTC payments, we further assess a set of mutually exclusive sub-categories of total spending: durable spending, non-durable spending, and healthcare spending.

- Transfers: Transfers from the household’s checking accounts to other accounts (either non-checking JPMorgan Chase accounts, external accounts owned by the household, or accounts owned by non-household members)

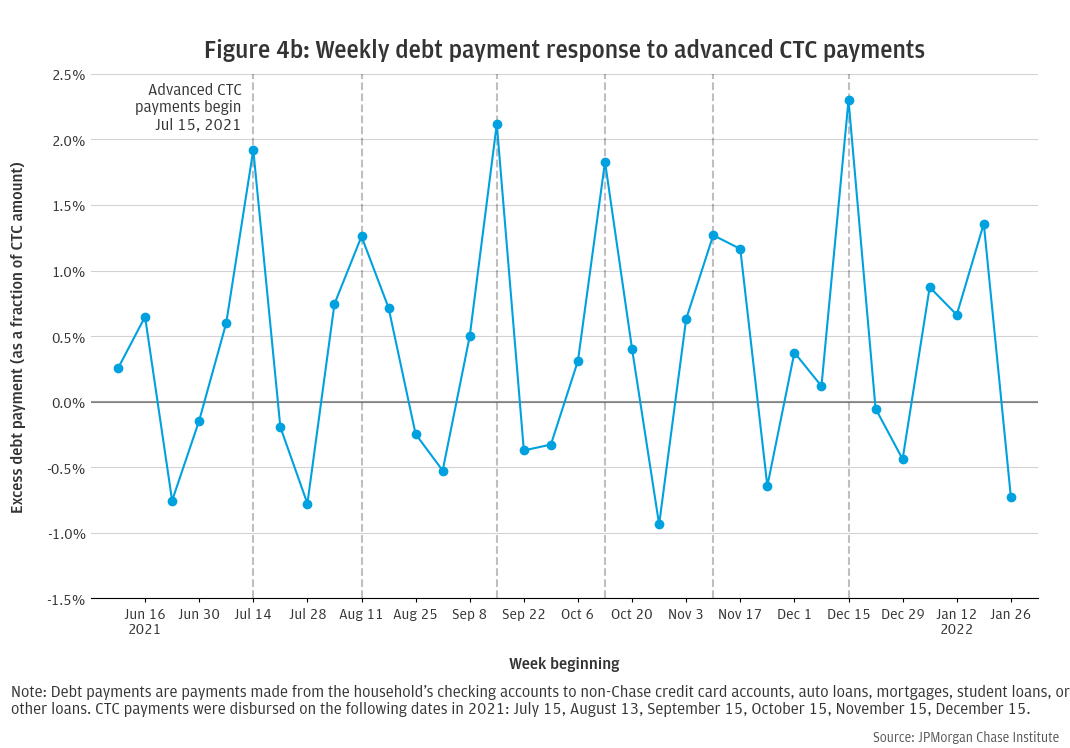

- Debt payments: Payments made from the household’s checking accounts to non-Chase credit card accounts, auto loans, mortgages, student loans, or other loans

Prior to use in regression, we scale the dependent variable via a two-step process, to account for both seasonality and differing spending levels across households.

Scaled value in week t= ((2021 week t value)-(2019 week t value))/(2019 median weekly total spending)

Note that the scaling denominator is always based on total spending, for every dependent variable. This is due to the relative rare occurrence of some types if consumption, for example healthcare spending, which often has a weekly median of zero for typical households. So that βτ can still be interpreted as a fraction of CTC amount, we also scale the CTC amount in the same way.

Accounting for credit card spending: Note that credit cards show up in two of our dependent variables, total spending and debt payments. The distinction here is Chase vs. non-Chase cards. We can observe any spending charged to a Chase credit card at a granular, transaction-level data. We see the transaction date and category, and can therefore include these transactions alongside other weekly spending categories. On the other hand, we cannot see details of how customers use their non-Chase credit cards. We can only observe the presence of other credit cards when a payment is made from a household’s Chase account to the non-Chase card bill. We therefore classify these payment transactions as debt payments, since the spending occurred prior and the payment represents paying down the debt owed to the credit card. We do not count payments toward non-Chase credit card bills as spending, since we do not know when or how the spending occurred, nor how much of the payment covers older debts on the card. Likewise, we do not count payments toward Chase credit card bills as debt payments, as we have already included this activity in our spending metrics.

Week variables: As noted in the regression specification, the independent variables of interest are household-level CTC amount and weekly dummy variables. We construct custom week boundaries so that the CTC payment lands as early in the week as possible. This enables the best understanding of consumption response, as each CTC week will include several days of observed spending following the CTC payment. Unfortunately, CTC payments are not scheduled based on day of the week, but instead land on the 15th of every month (or the preceding business day, if the 15th is not a business day). The result is that three CTC payments land on Wednesdays or Thursdays (July, September, December), two land on Fridays (August, October), and one lands on a Monday (November). To maximize post-CTC days per week, we construct our weeks to run Wednesday through Tuesday. This means that for five of the six CTC payments, the week of payment allows us to observe the payment day plus the 4 to 6 following days. Because November’s CTC payments land on a Monday, we only observe CTC payment plus 1 following day. This results in low consumption response estimates for November, since response to the payment gets distributed across 2 weeks.

Our analysis sample includes weekly data for each household beginning 9 weeks prior to the first CTC payment, and continuing through the end of January 2022. The first four weeks (9 to 6 weeks before the first CTC, or May 12 through June 8) serve as a reference period, during which behavioral differences between recipient and non-recipient households are established. When plotting the impulse response (βτ ) we subtract the average of the βτ for June 9 through July 7 (those before the first CTC payment) from each point in the plot, to level-set the series.

Weights: When regressing, we apply weights to non-CTC-recipient households so their demographics mimic those of the CTC recipients on key dimensions that differentiate households with and without children. We include three factors in this weighting scheme:

- Maximum age: The age of the oldest household member, as of 2021

- Adult count: The number of adults in the household, determined by the household’s total round 1 EIP amount received (limited to 1 or 2 adults, see above filtering discussion)

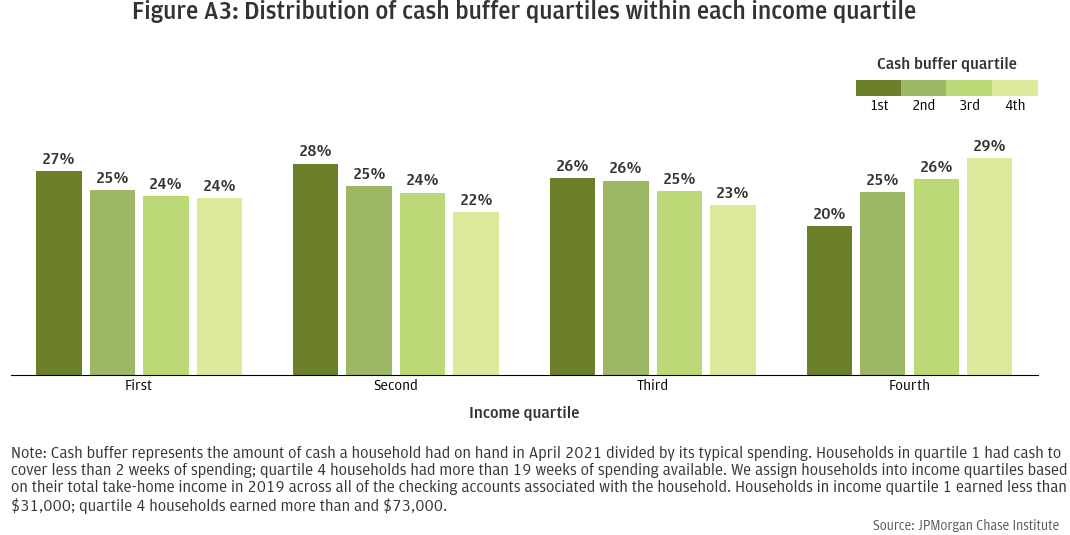

- Cash buffer quartile: The number of weeks of typical spending present in the household’s checking and savings accounts, in April 2021 (see Measures section above for details)

We compute weights based on the joint distribution of these three variables, as observed in CTC recipient households. For a target proportion based on the joint distribution in the CTC recipient group, and an actual proportion based on the joint distribution in the non-recipient group, household-level weights for non-recipient households are calculated as:

Weight=(Target proportion)/(Actual proportion)

Modeling sample: Prior to performing regressions, we apply additional filters to our analysis sample. First, we randomly select just over 300,000 households in each group (CTC recipients and non-recipients) from the full sample to enable efficient computation of the regressions. We also remove households with extreme values of scaled CTC amount or the dependent variable of interest (i.e., households with near-zero median spending). Finally, we remove households with extreme values of our weighting variables, specifically households with more than two adults.

Differing Trends by CTC Recipiency

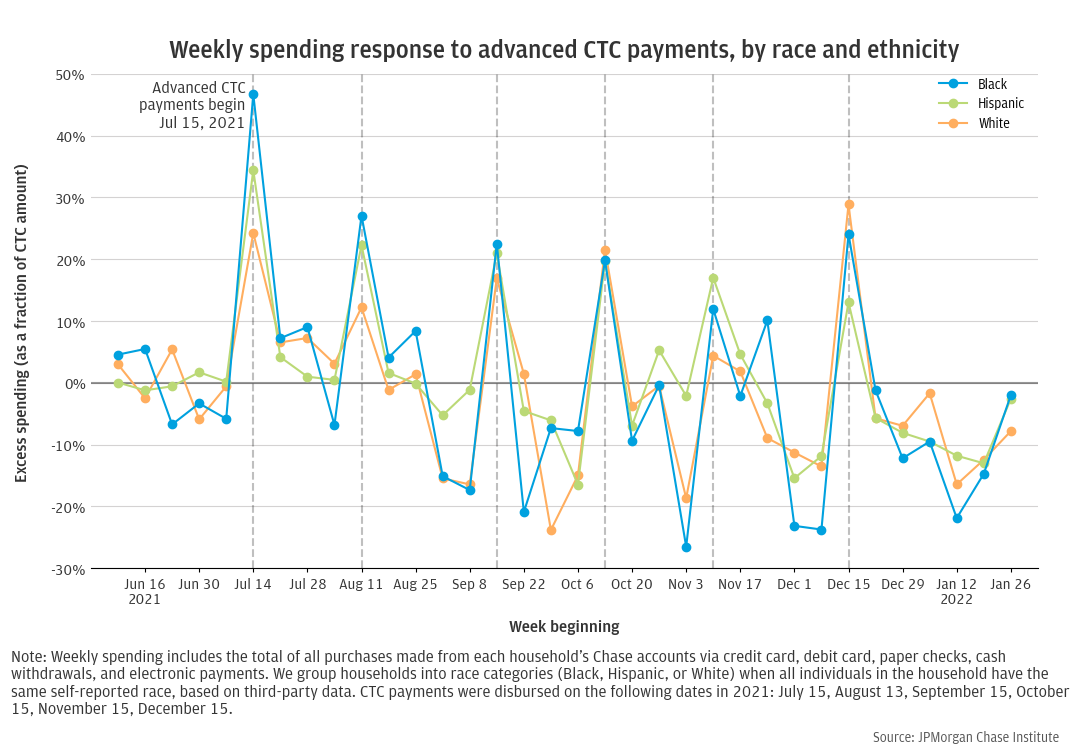

CTC recipient households are fundamentally different from non-recipient households in many ways and are therefore difficult to directly compare. Our regression approach was unable to fully isolate CTC effects from underlying differences in household type, despite weighting on several key differentiating factors: household maximum age, number of adults, and amount of cash buffer (see the appendix for details). Figure 2 illustrates this issue in its downward sloping trend, indicating that spending differences between CTC recipient and non-recipient households are not steady over time.

Previous Institute research has highlighted steeper balance trajectories for CTC recipient households in the months prior to the advanced CTC payments (see linked Figure 7). That report showed that CTC-recipient families had much higher balances than non-recipient families after the final EIP stimulus payments in March 2021 and depleted those balance gains over subsequent months. These balance trends indicate that CTC recipient families likely had different spending trajectories than non-recipient families in the months following the final stimulus payment, with CTC recipient spending declining relative to the non-recipient group over time. This relative deceleration of spending among the CTC recipients as they finish spending down their EIP money will be reflected in the estimated response to CTC receipt because “large EIP amount” is caused by a large household size which is very highly correlated with a household having children. Indeed, differences in spending between recipient and non-recipient households are larger earlier in our sample and decrease somewhat over the course of the year, indicating that changes in spending differences over time are likely driving the downward trend in Figure 2.

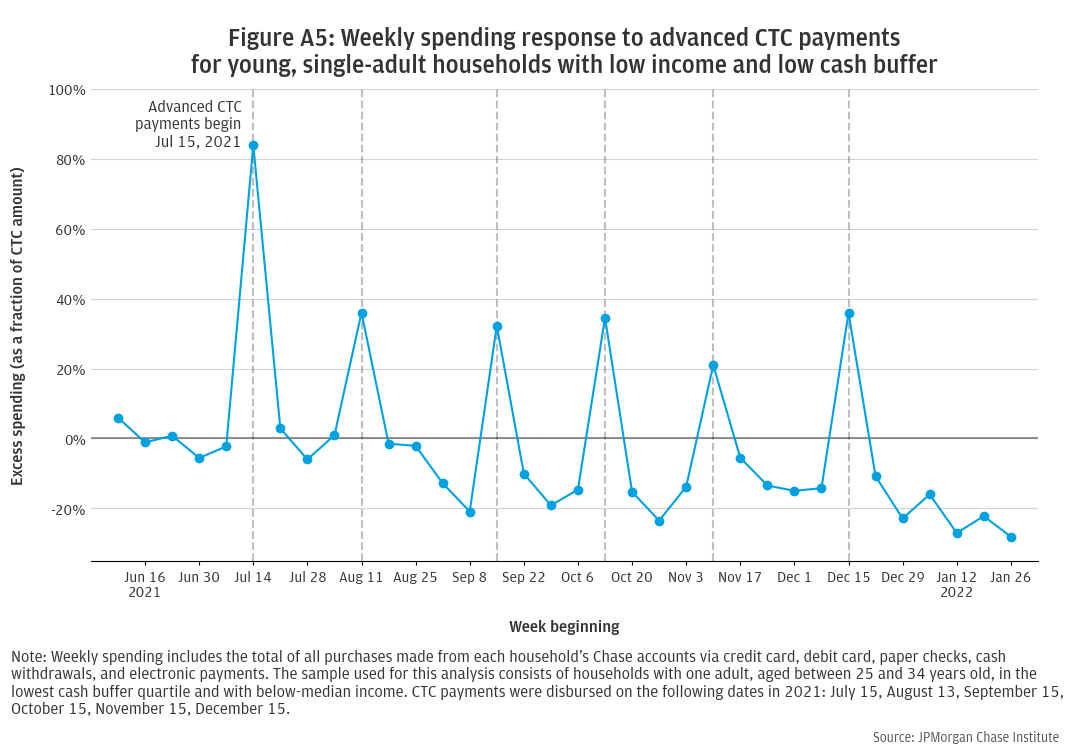

To assess how much these group-level differences in spending trends impacted regression results, we repeated our analysis on a subsample of our regression data. We held constant several key dimensions of differences between CTC recipient and non-recipient households with the goal of removing the underlying differences in spending trajectory. The subsample was restricted to young, single-adult households with low income and low cash buffer. This somewhat reduces the pre-existing differences in balances and EIP receipt and thus should reduce the variation in EIP-related deceleration between the CTC recipients and non-recipients. The resulting spending response shows a somewhat flattened trajectory, with monthly peaks and troughs at relatively constant levels, August through December (see Figure A5). Most analyses in this report focus on the overall regression sample, keeping in mind the source of this downward trend.