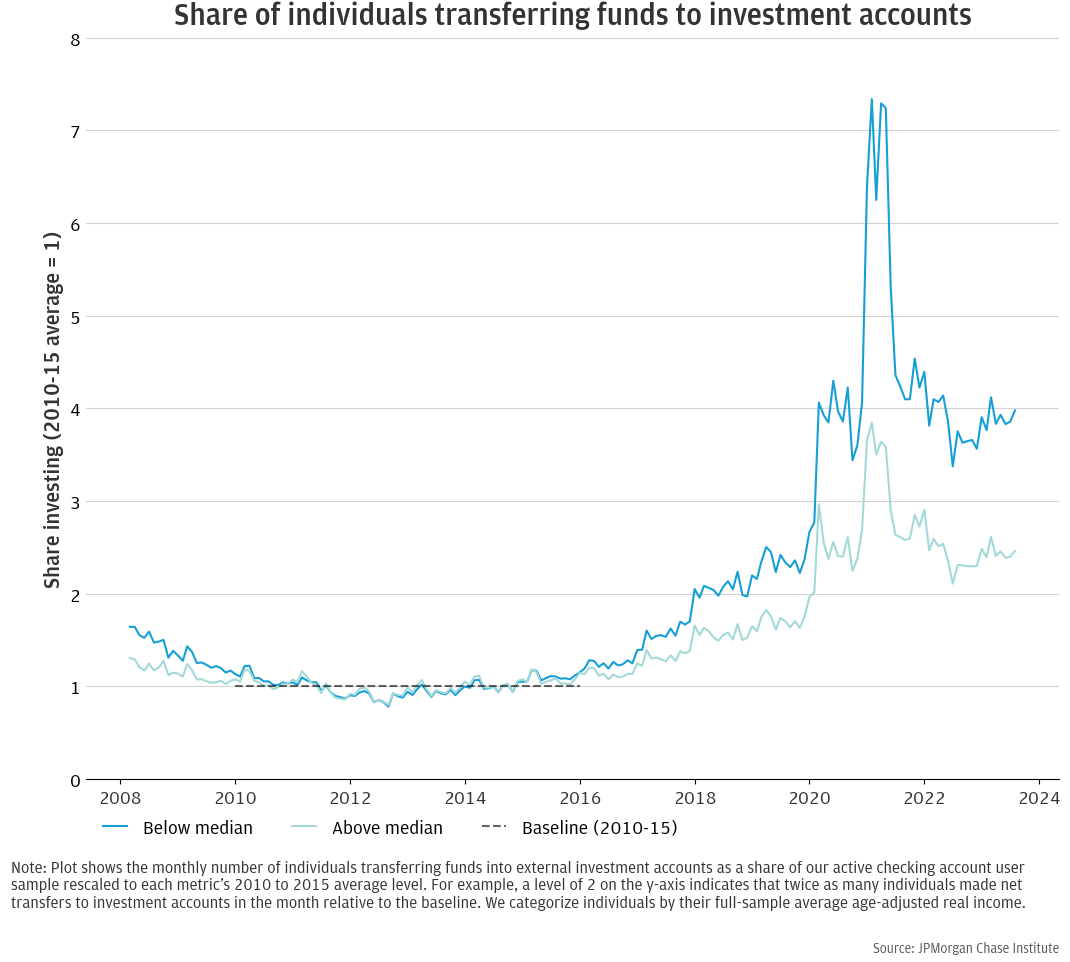

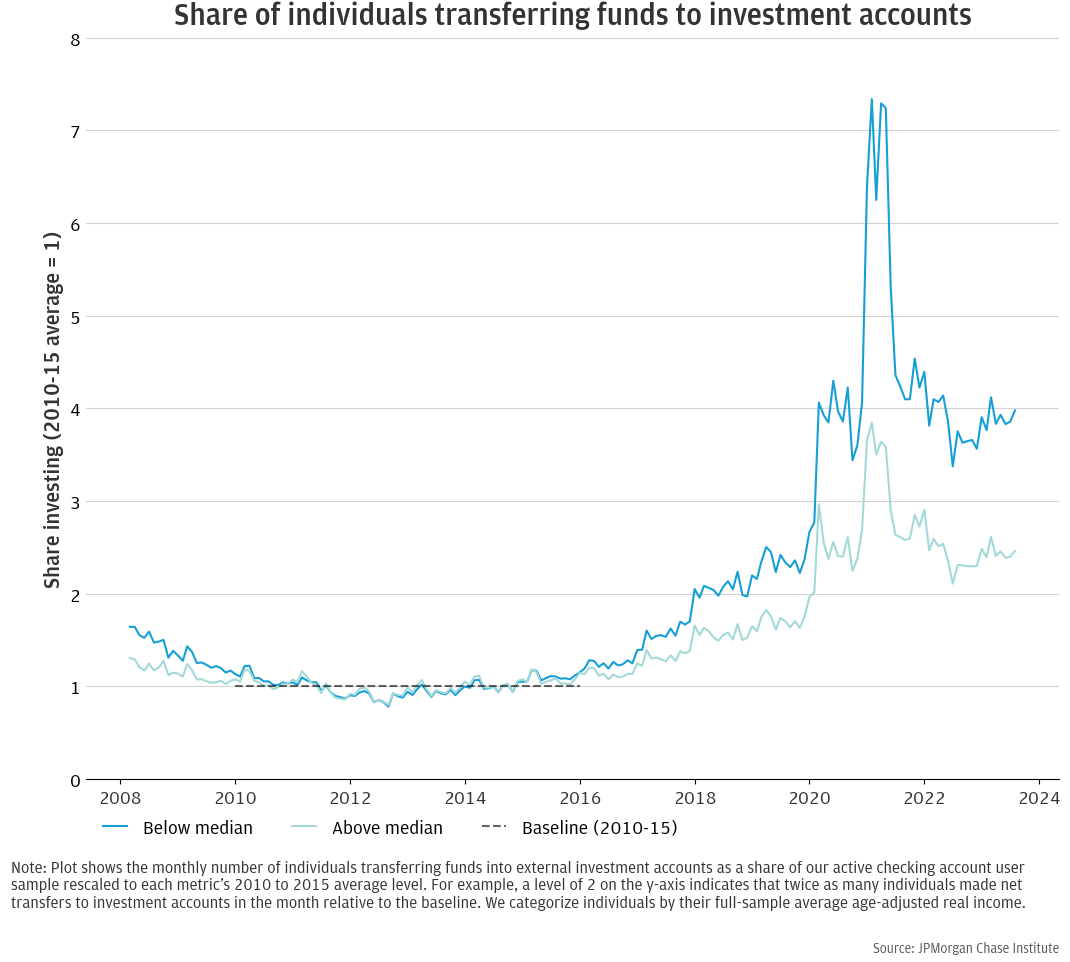

Figure: The share of investors with lower incomes rose steadily over the past decade—particularly during the pandemic savings surge.

Stories

By George Eckerd, Wealth and Markets Research Director

April 03, 2025

Since its founding in 2015, the JPMorganChase Institute has leveraged its unique, proprietary data to identify key trends in wealth building and their impact on household financial health. The data show U.S. households’ wealth accumulation has changed notably over the past decade. Our research focuses on changes in wealth, which complements public data that capture a snapshot of the distribution of wealth at a point in time. The most widely used public data source is the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances, which is fielded every three years. The Institute perspective of wealth is designed to help fills in the blanks left by this canonical survey, providing insight into economic drivers of the distribution of wealth over time and at a higher frequency.

Our research has documented significant changes in the distribution of cash holdings and financial investments, potentially raising prospects for changing wealth inequality dynamics. At the same time, wealth disparities are very large and have proven to persist over decades. This Take uses three main insights from our research that help frame recent changes in wealth building dynamics in the context of longer-run trends in wealth inequality.

Takeaway #1: Investing activity has surged since the pandemic, especially among lower-income and younger individuals, even though cash balances declined close to their pre-pandemic trends.

Takeaway #2: Structural factors—like the timing of asset purchases, differences in investment returns, and the accumulative nature of wealth—continue to reinforce wealth disparities.

Takeaway #3: Some trends, like higher wage growth and increased financial investment among lower-income individuals, could help reduce wealth inequality if sustained over an extended period.

While cash balances have returned to near pre-pandemic trends, investing activity has surged since the pandemic—especially among lower-income and younger people.

The pandemic period led to historic swings in the personal savings rate, from a post-World War II high of 32 percent in April 2020 to near-all-time-lows around 2 percent in June 2022. These changes coincided with large swings in cash balances, but cash holdings have largely normalized near pre-pandemic levels: the money was largely spent or moved into other stores of value. While cash balances have returned close to pre-pandemic trends, investing behavior has not.

On a monthly basis, the number of individuals moving money into investment accounts has risen two- to four-times the level a decade-ago, even though individuals’ median level cash balances have reached a relatively stable level. Lower-income and younger individuals’ transfers to investment accounts have risen the most.

Sustained wage growth and broadening participation in financial markets could help reduce disparities.

Pay for lower-income workers grew modestly faster than for higher-income workers over 2019−2024, extending trends seen during the robust labor market just prior to the pandemic. Paired with higher investing rates, shown above, this trend could erode disparities if sustained over time.

Wealth disparities depend on when people purchase assets and the returns they generate.

Tracking household financial behavior at a micro level, we find mechanisms that may sustain wealth disparities in ways that previously have been difficult to discern using publicly available data.

For example, the return that people earn on wealth holdings depends on the timing of asset purchases. Due to inequality in the labor market, the slow recovery from the Great Recession meant that income gains—an important determinate of wealth building—came later for lower earners. Stock market valuations were largely rising over this period, meaning lower-income investors transferred money to investment accounts when valuations were about 5 percent higher than those with high earnings levels. This will likely weigh on their investment returns relative to those with higher incomes and wealth. The canonical lens on the distribution of household wealth in the U.S.—the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances—is based on snapshots taken every three years, making it challenging to detect this specific kind of mechanism.

Sizing up the challenge.

Greater market participation by lower-income households means that future rises in asset prices will benefit more people, but it does not per se substantially erode existing disparities in wealth levels. The scale of wealth matters, as does the degree of inequality. According to Federal Reserve data, the total amount of wealth held by U.S. households is over $150 trillion, which is over ten times larger than annual wages and salaries. The growth of savings in financial assets for lower-income individuals is a positive signal for their financial health, but these savings rates represent a fraction of income.

Relatedly, wealth inequality accumulates over generations and is much larger than income inequality. Increases in wealth driven by asset prices, like rising home values—up over 50 percent since 2019—and the doubling of the stock market since 2019, disproportionately benefit those who already have sizable holdings.

The large stock of accumulated wealth also means that differences in returns on wealth—which have been shown in Institute reports (in stocks and crypto-assets) and academic research (in multiple recent studies on housing) to favor the already wealthy—exert a powerful force sustaining high levels of inequality.

As the Institute reaches its tenth year, our work will continue to use proprietary data to highlight policy relevant mechanisms that operating between markets, wealth, and the overall economy. These insights can help policymakers better understand the changing forces that will drive inequality over the next ten years.

George Eckerd

Wealth and Markets Research Director