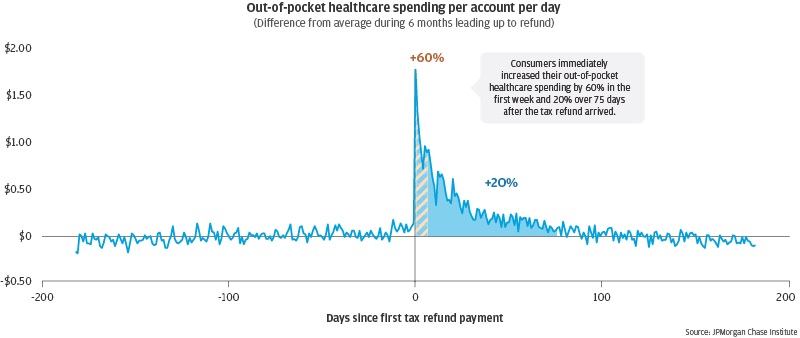

Figure 1: Families defer healthcare spending until they have the cash to pay for it

With the World Health Organization designating COVID-19 a global pandemic, the novel coronavirus is spreading in the U.S. at a pace that requires significant policy and personal interventions to contain and treat it. The economic impacts on households, businesses, and financial markets could be profound. JPMorgan Chase Institute research speaks directly to ways in which families, small businesses, and communities may be impacted by the effects of COVID-19, as well as how decision makers could shape policies to mitigate negative impacts. Below, we describe four key imperatives to weaken the blow from COVID-19 on societal welfare: keeping people safe and healthy; ensuring access to adequate income to meet basic needs; understanding the distinctive risks to small businesses; and boosting liquidity for households and small businesses. We describe lessons learned from natural disasters, like the Harvey and Irma hurricanes and specific potential interventions for policymakers, employers, and other influencers to provide relief from the economic effects of COVID-19.

Key imperatives during the COVID-19 pandemic

Families foremost need access to medical information and care. But our research has shown that, insofar as families might anticipate out-of-pocket costs for COVID-19 testing or treatment, cash-flow dynamics could influence families’ decisions to promptly seek healthcare services. Access to the COVID-19 test has thus far been limited in the U.S. due to delays in test roll-out and stringent testing criteria. Reportedly, testing and treatment for COVID-19 has cost patients thousands of dollars. Though the federal government, in coordination with insurance providers, has recently waived co-pays for testing, cost-sharing arrangements still remain unclear1. Emergency coronavirus relief legislation passed into law on March 18th, 2020, requires costs related to testing to be covered by private and public insurance plans but contains provisions that are not comprehensive to minimize out-of-pocket costs associated with treatment, recovery, and complications arising from COVID-19, as many public health experts have recommended. For example, a case that requires stay in an intensive care unit may incur costs beyond what is covered. With the risk of health systems being pushed to capacity, patients could easily be transferred to out-of-network facilities, resulting in high out-of-pocket costs.

The JPMorgan Chase Institute has examined how out-of-pocket healthcare spending behaviors connect to the rest of families’ financial lives. We observed that families’ healthcare consumption increases by 60 percent in the week after the arrival of the tax refund (Figure 1), and most of that bump in healthcare spending is for in-person healthcare services. This means that people defer care until they have the cash to pay for it. This is especially the case for families who have limited cash reserves—families in the lowest quintile of cash reserves (holding less than $530) exhibited a twenty-fold larger increase in their healthcare spending after the arrival of the tax refund than families in the top quintile of cash reserves (holding roughly $3,600 or more).

Of course, fears and, in some cases, grave illness stemming from the COVID-19 epidemic might cause patients to seek testing and care regardless of the out-of-pocket costs. COVID-19 patients who have to make an extraordinary medical payment to cover either testing or care, could experience lasting impacts to their financial lives including lower liquid assets to cover concurrent or future dips in income, as well as higher revolving credit card debt. This is especially true for older individuals.

Figure 1: Families defer healthcare spending until they have the cash to pay for it

With many businesses operating on reduced hours or closed entirely, and workers increasingly sheltering in their homes or unable to go to work, many workers will face reductions in labor demand and earnings. Institute research has documented that families experience significant income volatility, and that the lion’s share of this volatility stems from within jobs, as opposed to transitions between jobs, with low-income families most susceptible to downside risk.COVID-19 will likely exacerbate downside risk for hourly workers, who may see their hours cut and are the least likely to have paid sick or family leave to quarantine or care for themselves or others. In contrast, salaried and high-skilled workers are more likely to be able to continue working from home and to have paid leave and vacation time they can use to cover their needs to stay home. Only 61 percent of workers in service occupations had access to paid sick leave in 2019, compared to 91 percent of workers in management, professional, and related occupations. Furthermore, only 31 percent of workers in the lowest 10 percent of average hourly wages have access to paid sick days, in contrast to 94 percent of workers in the highest 10 percent of average hourly wages. Put simply, hourly workers, many of whom work in sectors like leisure and hospitality, will be disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 and could experience the largest income losses.2

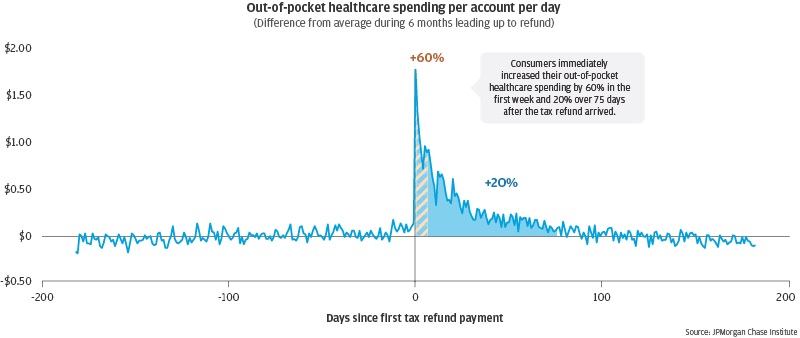

Such income losses translate directly into decreases to spending and wellbeing, particularly for those with less of a cash buffer and who experience more sustained losses. We see that, in general, families cut their spending when they lose a job involuntarily by about 5 to 10 percent with steeper cuts observed among families with lower liquid assets. Discretionary spending in particular, such as on flights, hotels, restaurants, and retail, declines after job loss. In the context of COVID-19, households may cut their consumption in these categories to offset losses in income—though such expenditures may decrease even more significantly due to families adhering to mobility restrictions and practicing social distancing. Among families who experience more sustained cuts to their income or remain unemployed for a more prolonged period, we observe steeper cuts to families’ expenditures, including basic necessities, such as groceries and healthcare spending (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Job loss causes a drop in discretionary spending and student loan payments, but the long-term unemployed also cut essentials when unemployment insurance (UI) benefits run out

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

If prior experiences of job loss are a good indicator, Figure 2 also illustrates that as families begin to experience the financial impacts of COVID-19, they may begin to defer debt payments. These include mortgages, auto loans, credit cards, and perhaps most immediately, student loans3. All debt payments are “irregular” to a point, but student loan debt appears to be among the first obligations families stop paying when they face financial distress, evidenced in the case of job loss (among unemployment insurance recipients, Figure 2) and after hurricanes (see Figure 3 in case study below). In general, student loan payments are much more volatile than auto and mortgage payments.

That said, we see that income dips, particularly deeper and longer drops, are also associated with mortgage delinquency. For borrowers who defaulted on their mortgage, income dips preceded default regardless of the homeowner’s income level, home equity, or mortgage payment burden.

During a pandemic, vehicles to manage this volatility may not be as available as they would be in other contexts. As Institute research has shown, some individuals turn to the Online Platform Economy to supplement their income when income from other sources dips. This is particularly true for men, who mostly turn to transportation platforms. Indeed, as mobility restrictions set in, demand for delivery services is surging as some are already reporting. In the short run, some individuals may opt for ridesharing as a safer alternative to public transit. But as the number of COVID-19 cases increases and communities shut down more completely, demand for, and supply of, rideshare is likely to fall, reducing its viability as a means of generating additional income.

Volatility impacts small businesses as well. As COVID-19 spreads, revenue volatility could cause more small businesses to shut down, particularly those with more limited cash liquidity and those in minority neighborhoods. The Institute’s research has shown that across the board, small businesses have volatile, irregular, and potentially unpredictable cash flows, (21 percent of firms across the 25 cities we studied). This is true especially for newer businesses. They also tend to operate with a limited cash buffer—typically enough to cover two to three weeks of outflows—and firms with limited cash liquidity are less likely to survive and grow. We have shown that among small businesses with irregular cash flows, 46 percent exit the small business sector within the first four years.

As mobility is restricted, consumers, both local and non-local visitors, are less likely to shop in person. Consequently, small businesses are likely to see a significant drop in revenue while commercial activity cedes. The uncertainty around the duration of these protective measures against the virus make a cash buffer even more important for small businesses facing potentially weeks of revenue loss that could impact their ability to operate. Businesses with more volatile revenues and expenses may specifically benefit from programs that make liquidity more accessible, like expanded grants and loans.

Moreover, small businesses in different sectors may experience the effect of COVID-19 differently due to it being a public health emergency. Our work on the financial impact of hurricanes (see Case Study below) showed that while construction and repair and maintenance firms recovered quickly after landfall, health care services and real estate firms were not as resilient. As COVID-19 continues to spread and change consumer behavior, it stands to reason that businesses in sectors like restaurants and retail may see the greatest loss in commercial activity and subsequently require the most support. Importantly, small businesses in majority-minority communities and communities with lower amounts of human and financial capital have materially lower levels of cash liquidity and small businesses operating on smaller profit margins. Policymakers responding to the impact of COVID-19 on small businesses might target responses to communities in which small businesses typically have the least cash liquidity.

Massive disruptions to travel and decreased mobility within communities could cause sharp drops in consumption, impacting small business demand and accelerating growth in online spending. As noted above, mobility restrictions can change consumer inclination to shop in person. Such restrictions are already taking shape as COVID-19 spreads to all fifty states. Many employers are shifting to work-from-home arrangements and travel bans are taking effect. People are increasingly limiting movement within their communities, as schools, universities, houses of worship, and other facilities shutter their doors amid public officials’ recommendations and orders. Limited mobility both across and within communities will have profound impacts on consumption patterns and small business revenues. There will be winners and losers from the shifts in consumption patterns but also likely a large net drop in aggregate consumption.

Impacts of restricted travel will result in steep declines in revenue for travel and hospitality industries and non-resident consumer spending within communities. Institute research has shown that non-resident local spend, i.e. spending from visitors, represents roughly 14 percent of local commerce in the fourteen cities we studied4. This will fall sharply as travel is restricted, impacting the hospitality industry dramatically. This includes the leasing sector of the Online Platform Economy, which has grown substantially since 2013 and, as of October 2018, generated over $2,500 in monthly revenues for as many as 0.3 percent of families in cities such as New Orleans, LA and Austin, TX.

Local mobility restrictions may accelerate the shift to online spending, which, as Institute research has documented, has been growing rapidly and contributed to almost 80 percent of spending growth in 2017. This could exacerbate revenue losses to local small businesses in the short and medium run.

As an aside, it is worth noting that restricted local movement could precipitate greater welfare losses for lower-income and older consumers. Rapidly changing spending options and behaviors could impact segments of the population differentially, potentially resulting in greater welfare losses for lower-income and older individuals. This is for two reasons. First, we saw that high-income and younger consumers were driving growth in online spending (and spent the most dollars). Second, examining the distances between consumer residences and the establishments at which they shop, we found that lower-income individuals had larger distances to traverse to make their desired everyday purchases. These findings might suggest that lower-income families were more likely to visit a store in person and might bear more welfare loss than their higher-income counterparts when mobility is sharply reduced due to COVID-19, insofar as their options for maintaining consumption are more limited.

In many ways, Hurricanes Harvey and Irma are instructive case studies of the economic impacts of a near-complete shutdown of a community for even just one week. We examined the impacts on families, small businesses, and local commerce in Houston and Miami5.

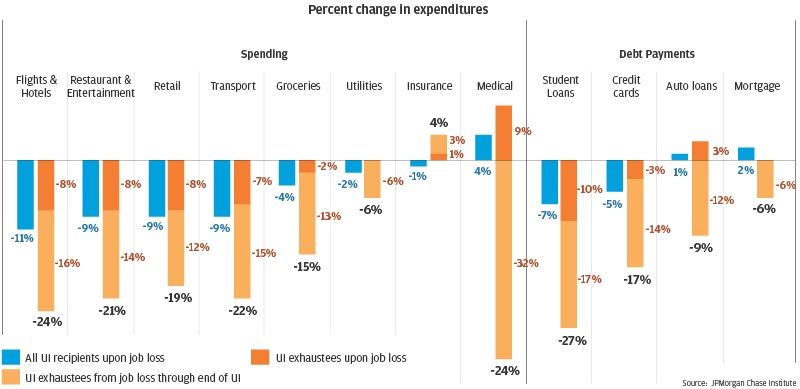

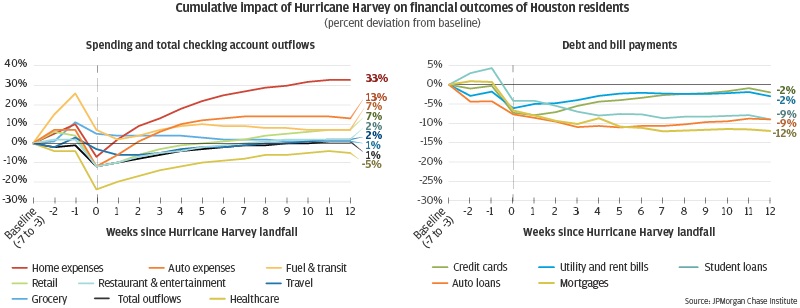

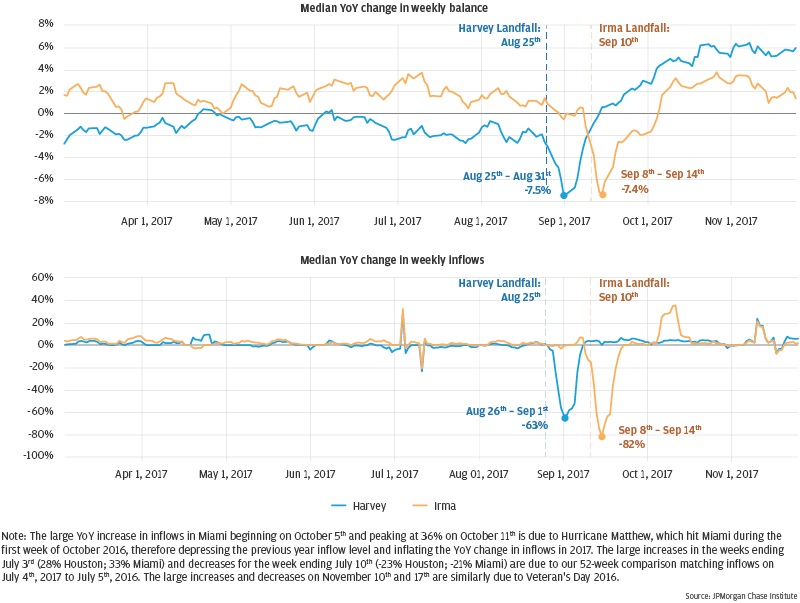

We found that families’ checking account inflows, including income and inbound transfers, temporarily dropped by over 20 percent, or roughly $400, in the week of hurricane landfall among both Houston and Miami residents. Checking account outflows, including spending, debt payments, and outbound transfers, dropped by more than 65 percent around the day of landfall and by more than 30 percent, or roughly $500, in the week of landfall (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Families in Houston and Miami exhibited large drops in daily checking account inflows and outflows in the week of landfall of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, respectively

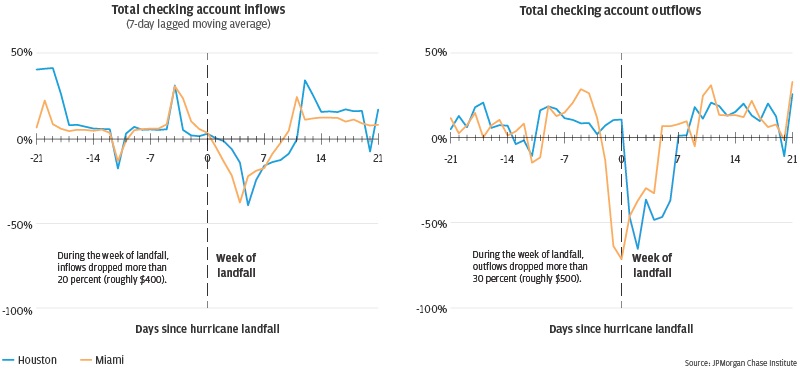

Some spending categories, notably fuel, grocery, and home expenses, saw increases in preparation for the hurricane. However, in the week of landfall, consumers cut spending across most categories. Healthcare spending dropped by more than 50 percent and still remained lower twelve weeks after, suggesting that families deferred (potentially routine) healthcare consumption during the hurricane even though the hurricane itself likely generated new healthcare needs. Families also cut their debt payments and still hadn’t caught up on them twelve weeks later (Figure 4).

We observed even larger impacts on small businesses. Institute research on the effect of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma shows that in the week of landfall small business revenues dropped over 60 percent and cash balances dropped by over 7 percent. Revenue losses were larger for small businesses in certain industries (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Families in Houston increased spending on fuel, groceries, and home repair in anticipation of Hurricane Harvey and cut spending and debt payments across the board during the hurricane

Notably, most small businesses in the Houston and Miami metro areas showed considerable financial resiliency in the weeks after Hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Large reductions in inflows were typically matched by decreases in outflows of a slightly smaller magnitude, thereby mitigating the decline in cash balances. The typical firm experienced a recovery in inflows in the subsequent week and a somewhat slower recovery of outflows within two to three weeks. Twelve weeks after landfall, most firms saw increases in their cash balances relative to the previous year, although some industries (construction and repair and maintenance) experienced stronger recoveries.

We are likely to see some of these same impacts as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, large drops in inflows and outflows for many families and businesses alike and a surge in preparatory spending as households stock up at grocery stores and drug stores. In addition, with many healthcare providers providing more limited care, many families will defer healthcare just as we saw during the hurricanes.

The picture during the COVID-19 pandemic will likely look qualitatively different from a hurricane, in terms of both the mix of industries that win and lose as well as the longer duration of economic and social disruption likely to be faced. It is difficult to deliver anything to or within a hurricane-affected zone. But during COVID-19, online purchases and delivery services are surging as families remain in their homes. In addition, while hurricanes and viruses can impact the rich and poor alike, the sustained economic disruption from COVID-19 is likely to disproportionately impact the lives of low-income families and small businesses with less of a cash buffer. Below, we provide a set of interventions that concentrate on quick ways to build this cash buffer for the most impacted families, small businesses, and communities.

What really makes families and businesses more financially resilient in the face of volatility is having a liquid cash buffer. In general, we estimate that families need roughly six weeks of take-home income in savings to weather a simultaneous income dip and expenditure spike. Overall, 65 percent of families lack a sufficient cash buffer to weather this event. Families with larger cash buffers are more resilient in the face of income volatility: they cut their everyday spending less when they experience a drop in earnings or lose their job entirely. They are less likely to default on their mortgage after a negative income shock. They also increase their expenditures less when they receive a major cash infusion, like a tax refund. Businesses with a larger cash buffer are less likely to close down. Therefore, it is imperative to find ways to quickly get cash into the hands of those families and businesses most affected. It is worth noting that some cash infusion opportunities are already in motion: tax refunds, the fall in oil prices, and interest rate cuts could put money in families’ pockets. Below we describe past evidence of how these effects could buffer against families’ spending losses from concurrent income drops. Measures to limit the spread of COVID-19 could mute these spending responses, which were observed without social distancing efforts.

With the vast majority of families receiving their tax refund in February, March, or April, many are receiving a major cash infusion just as the spread of COVID-19 takes off in the U.S. We document that more than 70 percent of families receive a tax refund during tax season, and these families tend to be lower-income, younger, and have lower cash reserves. Tax refunds represent roughly six weeks’ worth of income. For roughly 30 percent of tax refund recipients, the day they receive the tax refund is the most cash-flow positive day of the year. In other words, tax refund recipients are exactly the families who need the tax refund the most. Our evidence shows that expenditures increase dramatically in the weeks after the tax refund arrives, particularly for families with the least cash reserves. Between January and March of 2020 oil prices fell by more than 50 percent. Institute research has shown that the 25 percent drop in gas prices between 2014 and 2015 caused families to increase consumption. Families spent 58 percent of their potential annual savings from lower fuel prices (an average of roughly $630), including 24 percent on gas and 34 percent on non-gas goods and services. In the current environment, this could be a boon to many families and the businesses where they shop, except for markets that are exposed to the supply side of the oil and gas industry. Families could also leverage fuel savings generated by simply not driving, a potential outcome of limited mobility, quarantines, and containment zones.

The Federal Reserve’s cuts to its benchmark federal funds rate of 150 basis points to an interest rate range of near zero (0% - 0.25%) makes cheaper access to credit a means of giving people payment relief—to the extent that these cuts to short term interest rates are passed through to consumers. Institute research has shown that a predictable drop in monthly mortgage payment from the Federal Reserve’s low interest rate policy between 2010 and 2012 led to mortgage rate resets which, on average, represented over 5 percent of monthly income. Over a full two-year period afterwards, homeowners increased their spending, partially financed through credit card borrowing, above the total amount of their mortgage-related savings. The refinance boon currently happening will put money into the pockets of those borrowers who chose to refinance but in many cases only the most credit-worthy and financially savvy borrowers take advantage of this channel. Indeed, there are costs and frictions associated with refinancing that may limit benefits to select households.

As the government contemplates and takes aggressive actions to provide relief against the economic impacts of COVID-19, below we describe potential interventions for policymakers, employers, and other influencers to quickly get cash into the hands of those most affected quickly.

This makes existing policy frameworks, eligibility criteria, and delivery mechanisms important for operationalizing new relief measures.

We organize these intervention ideas into efforts to boost income, decrease expenses, and increase liquid assets.

Efforts to boost income:

Efforts to decrease expenses:

Efforts to increase liquid assets:

In summary, our research underscores the profound impacts COVID-19 could have on families’ ability to meet their basic needs, such as purchasing groceries, healthcare, and paying their mortgage, and for small businesses to stay afloat. Families and small businesses with low cash buffers are most vulnerable to the economic impacts of COVID-19. Efforts to provide relief should target the most vulnerable sectors of our society and economy. in many ways Hurricanes Harvey and Irma are case studies of the economic impact of a near-complete shutdown of a community for even just one week.

Additionally, the recently passed Families First Coronavirus Response Act includes provisions for Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP to cover testing, though this is only as of March 18th, 2020. While the law also includes $1 billion to pay providers reimbursements for treatment for the uninsured, this may not be widely known. Costs for the uninsured, who are disproportionately likely to be lower income, could be insurmountable for those who can’t afford it ($500 out of pocket).

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act signed by President Trump on March 18th, 2020 contains provisions to expand paid family and sick leave; however the scope for such expanded leave is more narrow than obligations included in the original version of the bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives. The most important provision seems to be that eligible employees include those who work for employers with fewer than 500 but more than 50 employees, with some specific exceptions, such as the healthcare mention here.

The Department of Education recently suspended federal student loan payments and waived interest during the national emergency.

Local Commerce as used here captures observed debit and credit card transactions. See: “What is Local Commerce?”

Notably, there were some important differences between these two events. Hurricane Harvey quickly intensified into a Category 5 hurricane delivering more than forty inches of rain on Houston, giving little time to prepare or evacuate. In contrast Miami was largely spared from Hurricane Irma, receiving just four inches of rain, and residents were told to evacuate in advance of landfall.

The Emergency Family and Medical Leave Expansion Act expands FMLA on a temporary basis, covering those employers with fewer than 500 employees. It lowers the eligibility requirement such that any employee who has worked for the employer for at least 30 days prior to the designated leave may be eligible to receive paid FMLA. However, it only allows an employee who is unable to work or telework to care for their child if the child’s school or place of care is unavailable due to a public health emergency, limiting eligibility to a very narrow case. The Emergency Paid Sick Leave Act expands paid sick leave eligibility, but places caps on paid sick leave wages and importantly exempts certain employers and allows employers of healthcare workers and emergency responders to exclude such employees from paid leave.

The Emergency Unemployment Insurance Stabilization and Access Act of 2020, passed on March 18th, 2020, provides $1 billion for emergency grants to states for maintaining unemployment insurance benefit processing and payment. It also extends UI benefits by an additional six months. It also gives states the flexibility to expand UI eligibility and waives the requirement that persons be actively looking for work to qualify.

Authors

Chris Wheat

President, JPMorganChase Institute

Diana Farrell

Founding and Former President & CEO

Fiona Greig

Former Co-President