Figure 1: Revolving balance is calculated as the end-of-cycle credit card balance less payments made before the next billing cycle ends

The 32 million small businesses in the United States are a heterogeneous group that operate across many industries, contributing over 43 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product.1 One thing that they have in common is the need to manage their cash flows, which are often irregular (Farrell, Wheat and Mac 2018, 2020c). As demonstrated during the pandemic, cash liquidity can be essential in times of distress.

One way that small businesses can manage irregular cash flows is to keep cash reserves. Prior Institute research documented that the typical small business kept enough cash to maintain its usual outflows for 15 days in the event of a total disruption to its inflows (JPMorgan Chase Institute 2020).

Most small businesses have credit as another source of liquidity, often with credit cards playing a role. In 2019, there was $368 billion in small business commercial and industrial loans outstanding, and over 46 percent of this amount was for loans less than $100,000.2 The majority of loans in this size category were small business credit cards (U.S. Small Business Administration 2020). Many small businesses have credit cards: 79 percent of small employers had credit cards that were used for business purposes (NFIB 2012).

Credit cards may be personal or business cards, which are relatively new. Business credit cards have been offered since the 1980s, and card issuers began more active pursuit of this segment during the 1990s (Blanchflower and Evans 2004).3 Small businesses use both personal and business cards: 49 percent of small employers used personal cards for business purposes, with the smallest firms (less than 10 employees) more likely by 14 percentage points to use personal cards than those with at least 50 employees (NFIB 2012). The 2003 Survey of Small Business Finances reported 48 percent of small businesses use personal cards and 47 percent use business cards (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2010). Smaller firms were more likely to use personal cards (Blanchflower and Evans 2004).

Despite policy interest in small business credit more generally, there have been few studies of small business use of credit cards, a common and widely available financing instrument. Most studies relied on survey data (Blanchflower and Evans 2004; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2010; NFIB 2012), and the Survey of Small Business Finances was discontinued after 2003. More recent studies utilizing administrative data such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) Credit Card Database focused on consumer cards and cannot link card activity to other financial variables (CFPB 2019).

Policymakers and other decision makers considering the credit needs of small businesses may be interested in how firms use the financing instruments they already have. Our research used more than a decade of longitudinal data linking small business cash flows and their credit card activity. We provide insights on the trajectory of business card usage during a period—2010 through 2022—when business cards were available and more widely used.

In this report, we focused on small business credit cards and their use either as financing instruments (revolving) or as means of payment (transacting). While firms may use personal as well as business credit cards, the scope of this report was limited to business credit cards. We used de-identified administrative data from deposit and credit card accounts to analyze how small businesses use their credit cards for financing considering their cash flow circumstances. In particular, we found:

Our research sample was designed to analyze the interaction between small business finances and the use of credit cards as financing instruments. To our knowledge, this is the only dataset that links granular, longitudinal data on business credit cards and deposit accounts.

As in much of our small business research, the de-identified firms in our sample all have Chase Business Banking deposit accounts that meet our criteria for being active and small.4 We further restricted our sample to small businesses with one Chase business credit card linked through the owner(s) of the deposit accounts. This restriction makes the link between the small business finances and the credit card clearer, but it may not capture the complexity of how small businesses use credit cards to manage their finances.

Our unique data linking firm finances and credit card activity provides valuable insight into small business financing decisions that would otherwise not be possible. However, our research sample covers a segment that may not be representative of all small businesses, even those with credit cards.

Our focus on business credit cards suggests that firms in our sample are typically larger in comparison to those that use personal cards, but they are not so large that they have multiple Chase business cards even though they may have other cards. The appendix provides more detail on the sample and discusses this restriction and its implications. For the sample defined above, we created a longitudinal dataset based on the billing cycle of each credit card. See Box 1 for details on how we used billing cycles and transactions to construct revolving balances.

Credit cards can be used as a debt financing instrument, but they need not be used as such. At the end of the billing cycle, the account holder could either pay the amount of the bill in full or pay at least the minimum amount required by the due date. The former are transactors who may use credit cards for convenience or the opportunity to earn rewards. The latter are revolvers who carry a balance on their credit cards and pay those balances over time. If the account has a grace period, card holders typically do not incur interest charges on purchases if they pay their bills in full during the grace period, which often extends for at least 21 days after the end of the billing cycle.5 Revolving balances are typically subject to interest charges, but promotional rates or periods may apply. However, cash advances commonly incur interest charges immediately.6

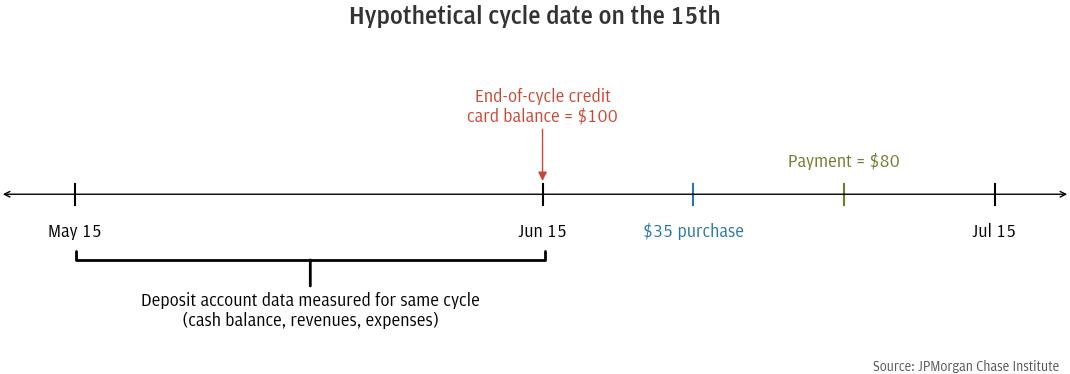

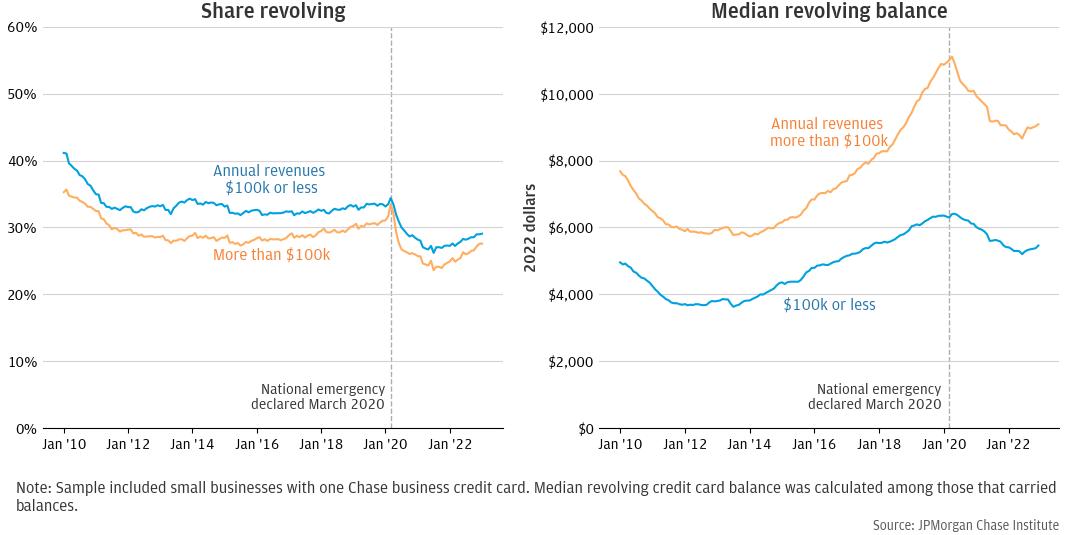

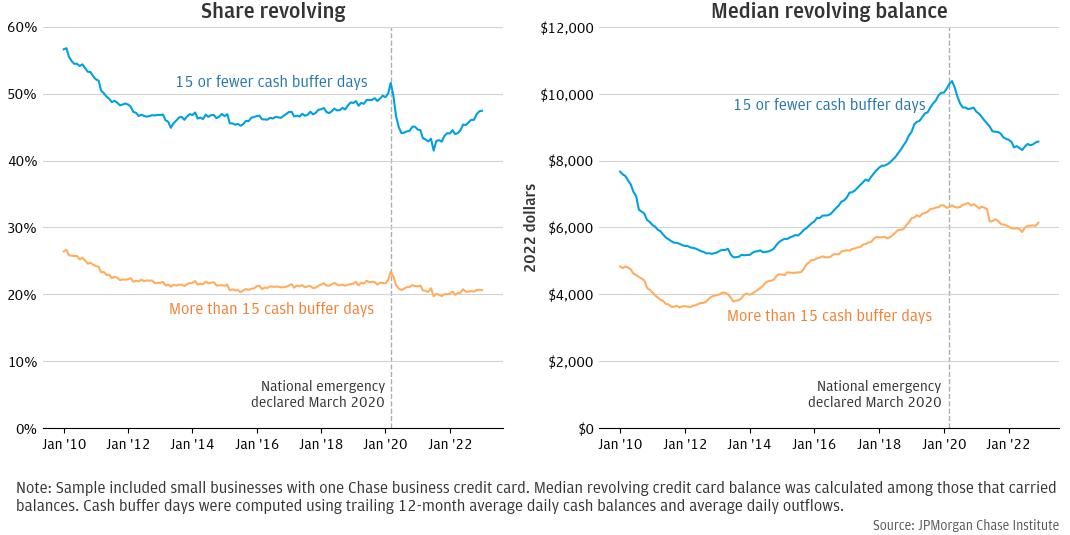

In our data, we cannot observe the minimum payment amounts, due dates, or whether a grace period applies. To estimate whether a firm revolves, we compared the total sum of credits to the account after the end of the cycle and before the next cycle ends to the amount due. For example, consider a hypothetical card with a billing cycle ending on the 15th of each month, as shown in Figure 1. If this card had an end-of-cycle balance of $100 on June 15, we took the sum of payments made between June 16 and July 15, the end of the following billing cycle. If that sum was less than $100, then that card revolved a balance by this measure. This method may underestimate the share of accounts that revolve if payments were made after the due date and before the next bill date.

Figure 1: Revolving balance is calculated as the end-of-cycle credit card balance less payments made before the next billing cycle ends

In this example, an $80 payment was made between June 16 and July 15, resulting in a $20 revolving balance. Note that this revolving balance may not correspond to the outstanding balance at any given time; there may have been additional purchases after the statement closed on June 15 and before the $80 payment was made.

If the sum of payments had been at least $100, this card holder would have been a transactor with respect to the June billing cycle. For cards with grace periods, transactors could utilize several weeks of financing without interest charges and smooth their cash flows within this period (Herbst-Murphy 2012).

In our sample, the majority of firms with a business credit card were transactors in any given month, either because they had no balance due at the end of their billing cycles or because they paid the bill in full by the next statement date.

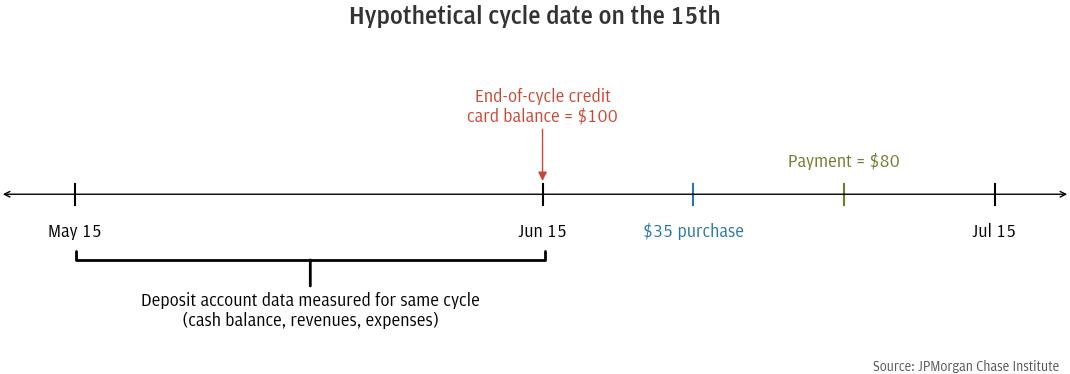

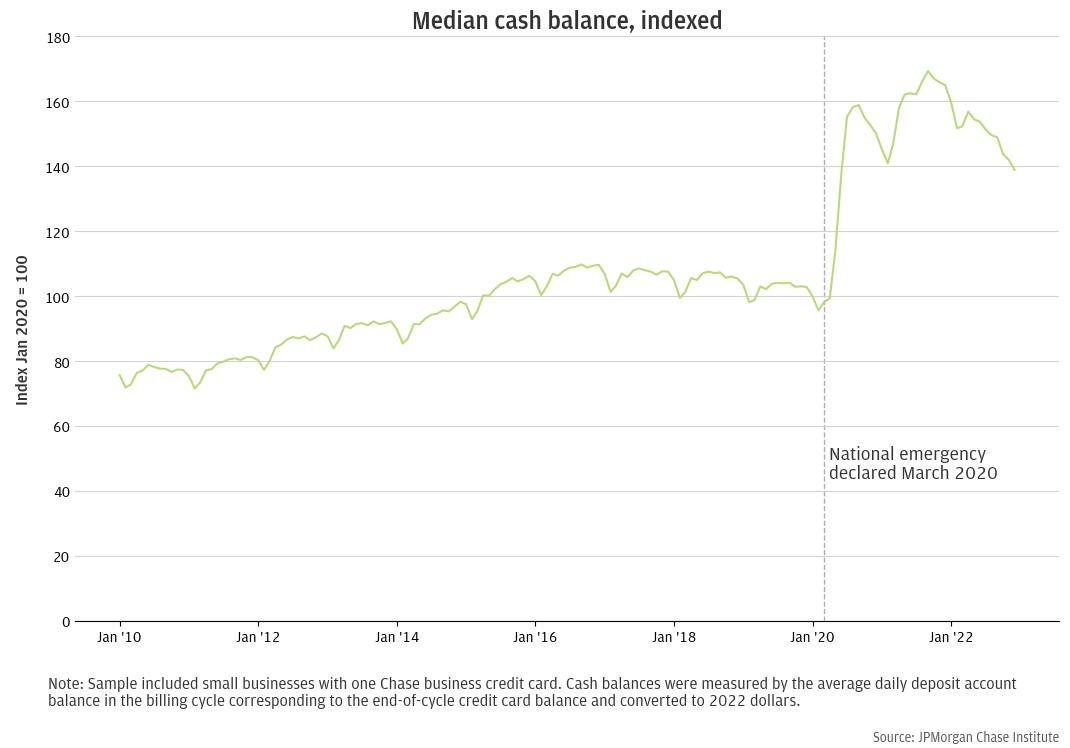

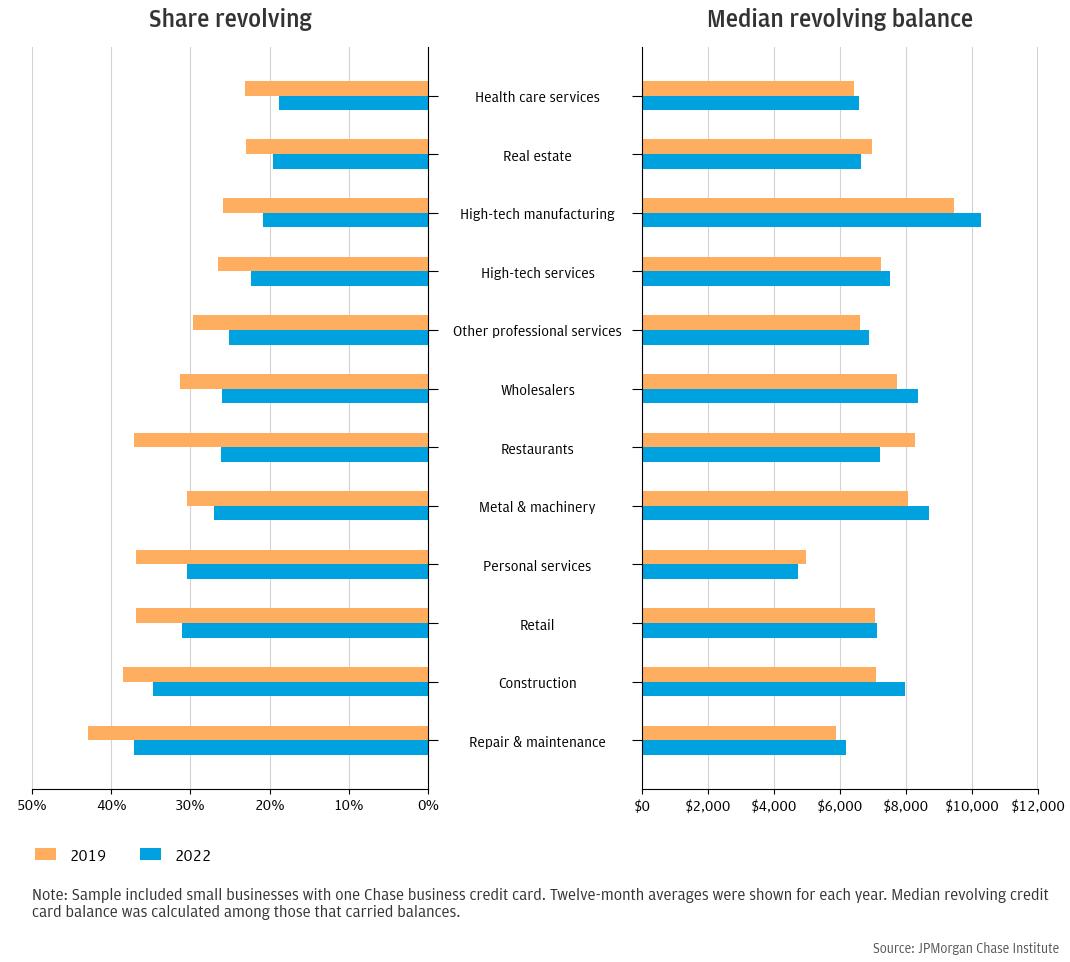

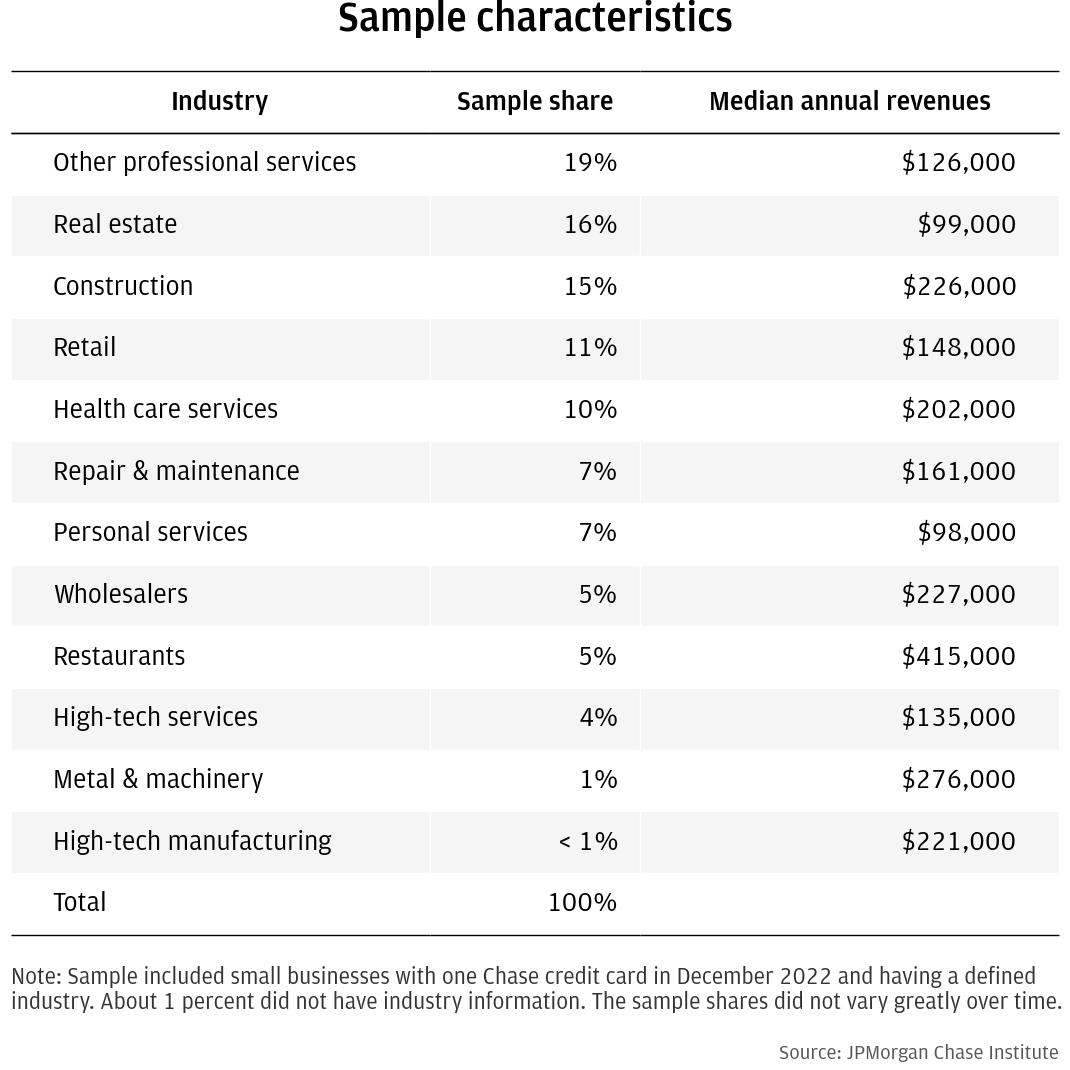

During our sample period of January 2010 through January 2023, approximately a third of firms revolved their credit cards between 2012 and 2020, as shown in the left panel of Figure 2. In the beginning of our sample period, this share was higher, but it is unclear whether this reflected higher revolving rates during the 2007-2009 recession.7 After the national emergency pertaining to COVID-19 was declared on March 13, 2020,8 the share of firms revolving decreased and has remained lower than 30 percent through 2022. While this share has increased since July 2021, whether these shares will return to pre-pandemic averages was not observed in our data.

Notably, public data sources do not provide a recent lens on small business borrowing patterns on credit cards. The most recent regularly reported survey data from the Survey of Small Business Finances found that 29 percent of business card users borrowed on their cards in 2003, up from 16 percent in 1998 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2010). A more recent one-time survey found 28 percent of small employers with a credit card used it for financing (NFIB 2012). While the Federal Reserve’s Small Business Credit Survey does not directly measure whether small business owners revolve debt on credit cards, it did report that 45 percent of nonemployer firms and 52 percent of employer firms use a credit card for external financing (Federal Reserve 2018, 2019).

Among firms that did not pay their bills in full, the typical revolving amount increased between 2012 and 2020 and decreased after March 2020. The right panel of Figure 2 shows the median revolving credit card balance in 2022 dollars increasing to about $8,000 in early 2020 and decreasing to approximately $7,000 in 2022.

Figure 2: The share of firms revolving their credit card balances declined after 2020

During the pandemic, many small businesses struggled and adjusted their operations considering public health guidelines, particularly immediately after the national emergency declaration (Farrell, Wheat and Mac 2020a, 2020b). It may appear counterintuitive that fewer small businesses revolved credit card balances during this time, and those that did reduced the amount they carried. However, many small businesses were able to pull back expenses quickly when they saw a decrease in revenues (Farrell et al. 2020), mitigating the effects of foregone revenues on balances. As government relief funds became available to businesses, such as Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) advances and Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, as well as Economic Impact Payments (EIP) directed towards individuals,9 deposit account balances grew. Some portion of those cash balances could have been used to pay down credit card debt, resulting in a lower share of firms revolving as well as lower median revolving balances.

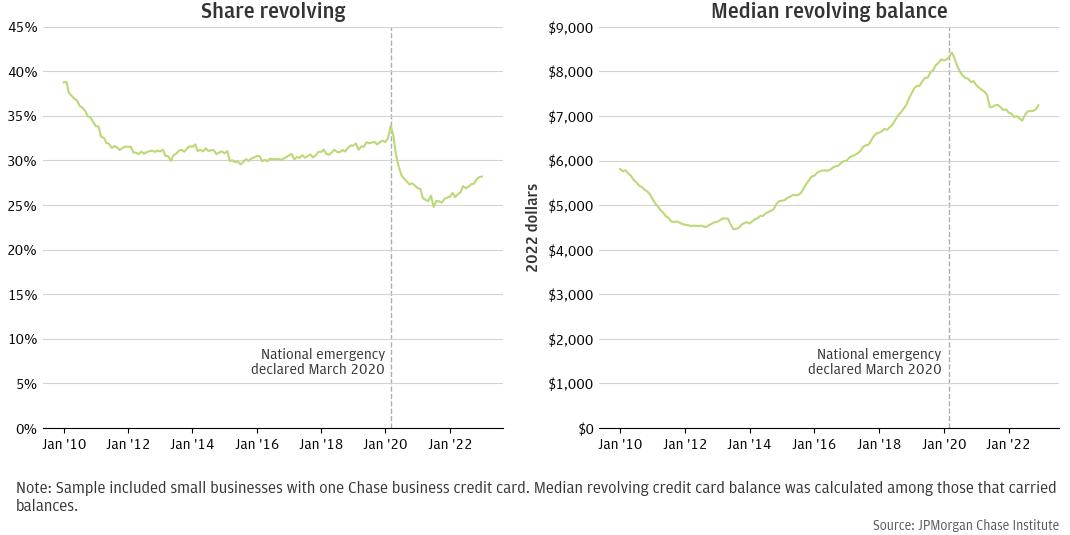

Figure 3: Deposit account balances increased after 2020

Figure 3 shows the median average daily deposit account balances, in 2022 dollars and indexed to January 2020. After May 2020, the median cash balances increased and were about 40 to 70 percent higher than in the beginning of 2020. This additional view of small business finances suggests that some firms were able to use their cash balances to pay down their credit card debt, perhaps in anticipation of further uncertainty related to the pandemic.

Figure 4: Larger firms were less likely to revolve but carried larger credit card balances when they did

Small businesses span a wide range of sizes and industries. Figure 4 provides a view of the share of firms revolving and the median revolving balances by firm size. Annual firm revenues were estimated using deposit account transaction data, and the sample was split into firms with revenues greater than $100,000 and those with $100,000 or less in revenues. Larger firms were less likely to revolve their credit card balances, but among larger firms that did revolve, the median revolving balance was higher than that of smaller firms. This is consistent with Blanchflower and Evans (2004), who found that sole proprietors and partnerships were more likely to carry credit card balances than corporations.

Despite differences in estimates, both larger and smaller firms saw similar patterns during our sample period, with a decrease in the shares revolving and the median revolving balance after March 2020. The increase in median revolving credit card balances leading up to 2020 was more pronounced among larger firms.

Figure 5: Share of firms revolving credit card balances varied by industry

Figure 5 shows the share revolving and median revolving balance among revolvers by industry for two years, 2019 and 2022. In each industry, the share revolving decreased from 2019 to 2022. However, differences between industries largely persisted. Some of these differences may be explained by differences in typical firm size. As Figure 4 illustrated, larger firms were less likely to revolve than smaller ones. Firms in health care services tend to be larger than those in personal services, and that size differential is partially reflected in the respective shares of firms revolving. Nineteen percent of firms in health care services revolved in 2022, compared to 30 percent of those in personal care services. However, size alone does not fully explain differences by industry. Table A1 in the appendix shows the median 2022 revenues by industry. Small businesses in construction have relatively high annual revenues at $226,000, but they also had one of the highest shares of firms revolving. In Finding 3, we used regression models to control for observable variables such as size and continued to see differences by industry.

Before the pandemic, about a third of small businesses with a business credit card revolved. As cash balances increased after the onset of the pandemic, the share of firms revolving decreased. This suggests that firms chose to pay down their credit card debt when their cash constraints lessened.

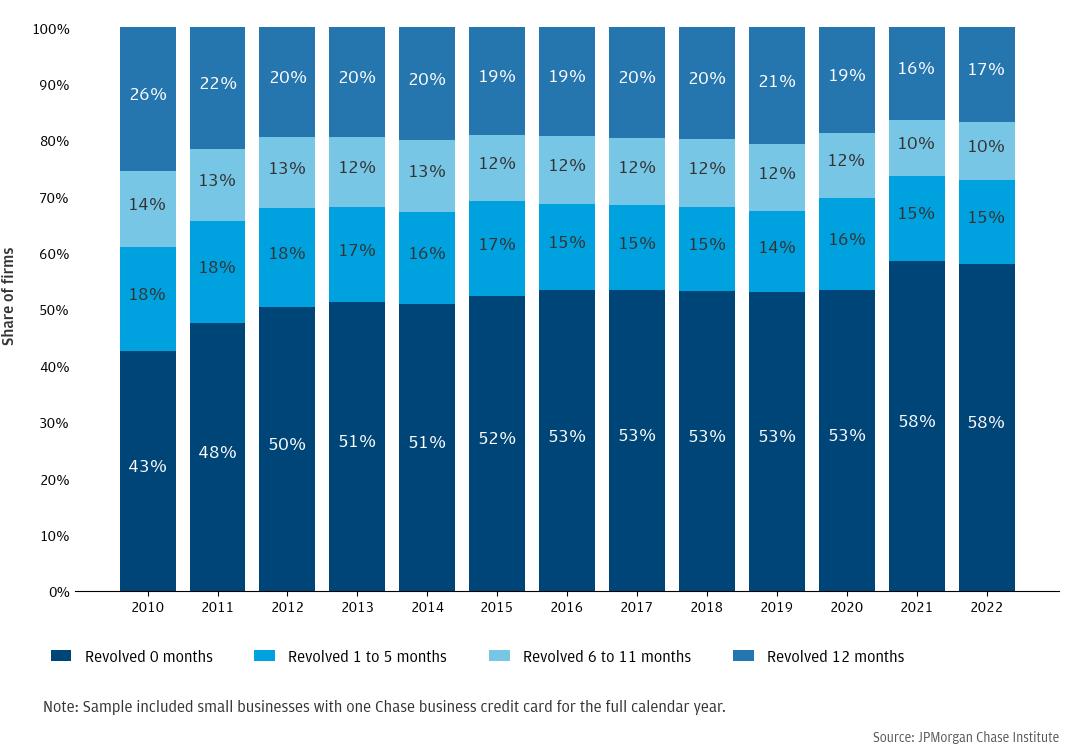

While Finding 1 showed the share of firms revolving in any given month, it did not show how stable this behavior was among small businesses. We find that it was quite stable—over the course of a year, most firms either transacted or revolved in each of the 12 months. About 25 to 30 percent revolved in some but not all months of a year.

Figure 6: About half of firms did not revolve over the course of a year

Figure 6 shows the shares of firms in each year based on the number of months in which they revolved their credit card balances. In most years, at least half of the firms never revolved over the course of the year, while about 20 percent revolved in each of the 12 months. The remainder of firms revolved in some but not all the months in each year. The declining share of revolvers after the onset of the pandemic is also present in this analysis: in 2021 and 2022, 58 percent of firms never revolved and 16 to 17 percent revolved in all 12 months, compared to 53 percent and 19 percent, respectively, in 2020.

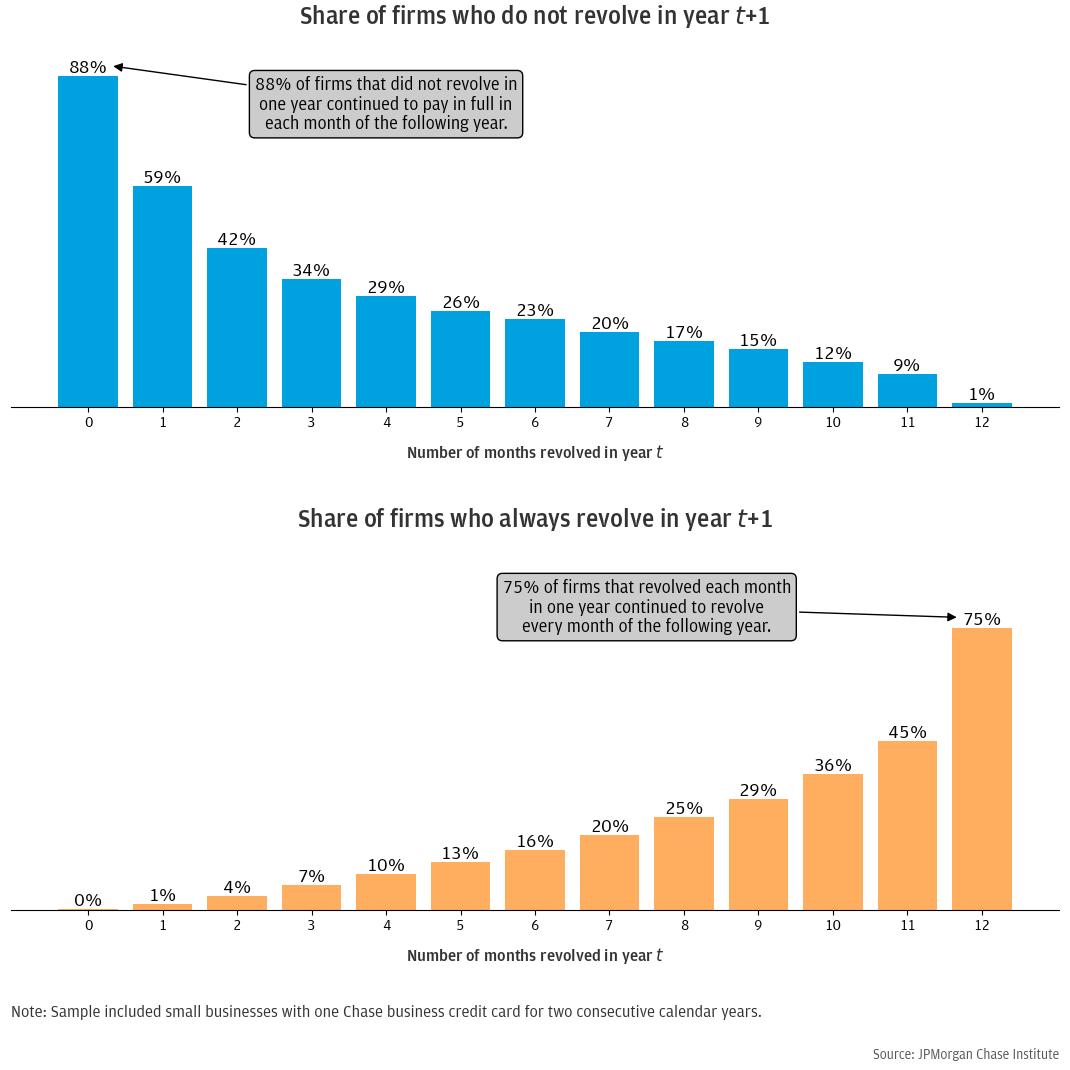

Figure 7: Most firms continued to be consistent transactors or revolvers in a subsequent year

The tendency of firms to be either consistent transactors or revolvers persists in a subsequent year. Figure 7 shows the share of firms that never or always revolved, based on the number of months they revolved in the prior year. Among firms that never revolved in one year, 88 percent continued to pay their credit card bills in full in the following year. Among firms that revolved for six months in a year, a minority—23 percent—would become transactors in each month of the following year, with the majority continuing to carry balances on their credit cards at least some months. At the opposite end of the spectrum, among firms that revolved each month in a year, only one percent became transactors in every month of the following year.

An analogous pattern emerged among revolvers. Among firms that revolved in each month of the year, the majority—75 percent—continued to revolve in each month of the subsequent year. Among firms that revolved in 11 out of 12 months of the year, 45 percent would revolve in each month of the next year. Firms that are consistently revolving their credit card balances for a year or more might consider whether lines of credit or working capital loans could better meet their needs. About 15 percent of the Small Business Administration’s (SBA’s) 7(a) loan proceeds were used to finance working capital in fiscal year 2017 (Dilger and Cilluffo 2022), but the sizable share of firms that consistently revolve credit card balances suggests that more small businesses could benefit.

Many firms are consistently transactors or revolvers over one to two years, suggesting that their routine use of credit cards is either as a means of payment or as a financing instrument. Nevertheless, a core credit card feature is flexibility: card holders may choose each month whether to pay in full or revolve. In the next section, we explore the circumstances around this decision.

Finding 2 documented that many firms either consistently revolve or transact on their credit card accounts. Firms may decide to revolve their credit card balances based on many different factors. For example, some firms may revolve when they have particularly high expenses or low revenues, using their credit cards to manage their cash flows, while other firms may pay the bill in full using cash reserves under similar cash flow circumstances. We used regression analyses to investigate how multiple variables factored into the decision to revolve.

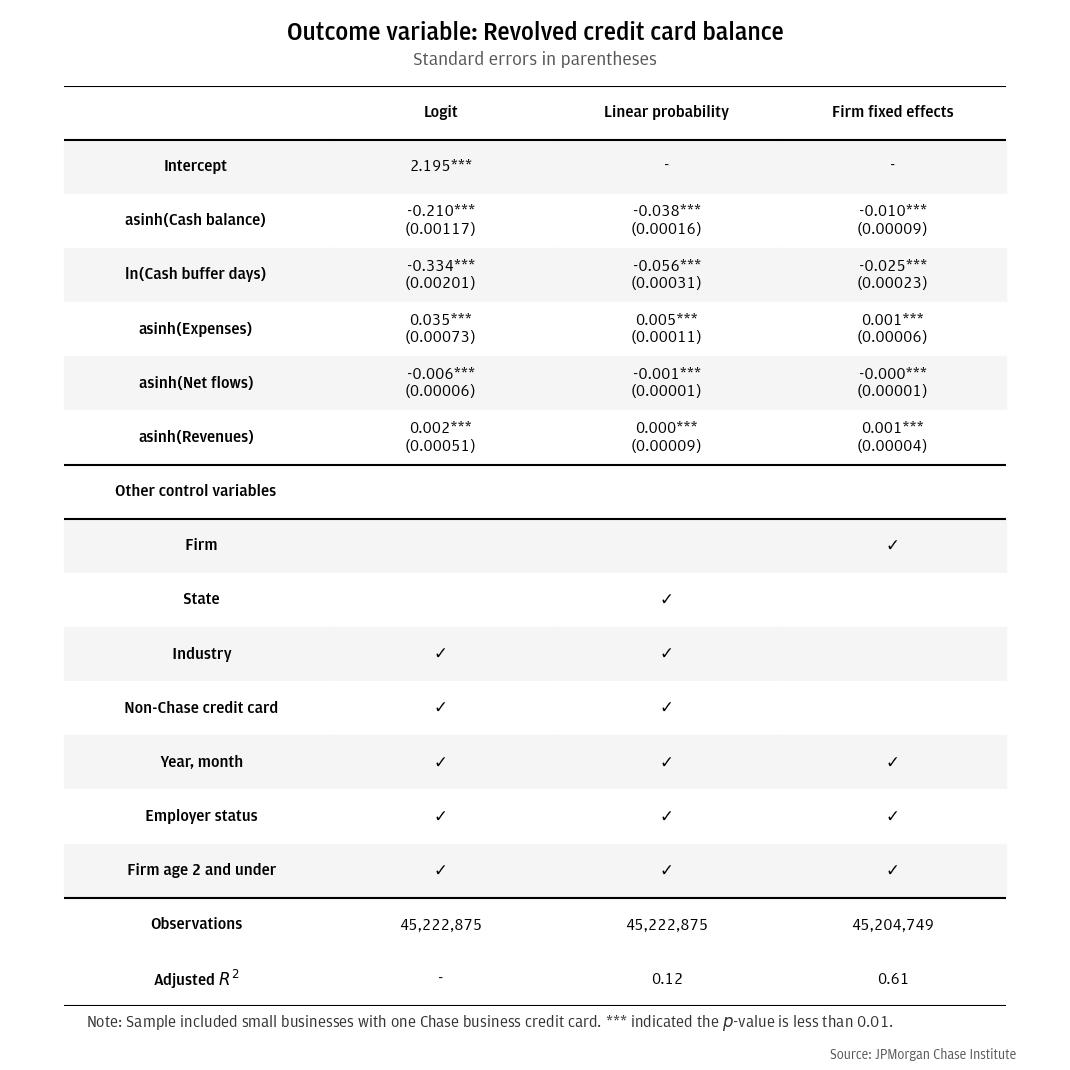

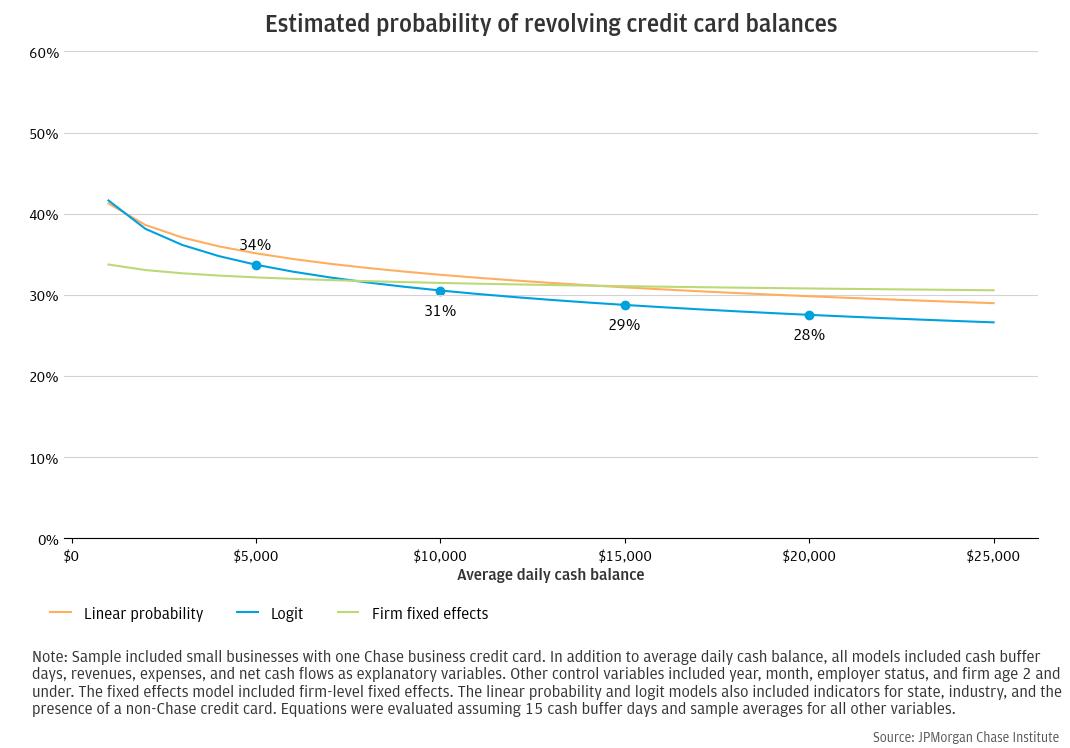

We estimated three models with a binary outcome variable: whether the firm revolved its credit card balance in that month or not. Each model included several financial variables for the firm: revenues, expenses, net cash flows, average daily cash balances,10 and cash buffer days.11,12 The linear probability and logit models also included firm characteristics as covariates to model differences between firms. A third model included firm fixed effects in a linear probability model. Firm fixed effects model within-firm variation and can also control for unobserved heterogeneity, such as the preference for revolving. Details of explanatory variables and results of each model are reported in the appendix.

Each of the financial variables was statistically significant, and the ones having the largest effects were average daily cash balances and cash buffer days. The coefficients on the other cash flow variables (revenues, expenses, and net flows) were also statistically significant but small. For example, all else equal, higher net flows were correlated with lower likelihoods of revolving. The relative the magnitude of these estimates were also consistent with the interpretation that more cash-constrained firms were more likely to revolve. That is, some firms managed a month in which net cash flows were lower than usual by using their cash balances, which were also the accumulation of past net flows, while others exercised the option not to pay their credit card bills in full. The existence of cash reserves meant that an irregular cash flow month need not be coupled with revolving a credit card balance.

Although both measure cash liquidity, we included both the average daily cash balance and the cash buffer days because each provides a different perspective of a firm’s cash liquidity. The average daily cash balance was measured for the billing cycle that resulted in the end-of-cycle balance on the credit card bill, providing a gauge of the cash available at the time of the billing statement. Cash buffer days, which measure the number of days in which a firm could maintain its usual outflows in the event of a disruption in its inflows, differ in two ways. First, it normalizes the cash balances by a measure of the firm’s size—its outflows. For example, a $10,000 cash balance may be a large reserve for a small firm with low expenses or a small reserve for a large firm. Second, we calculate cash buffer days using the trailing year’s average daily cash balance and outflows to smooth short-term fluctuations.13

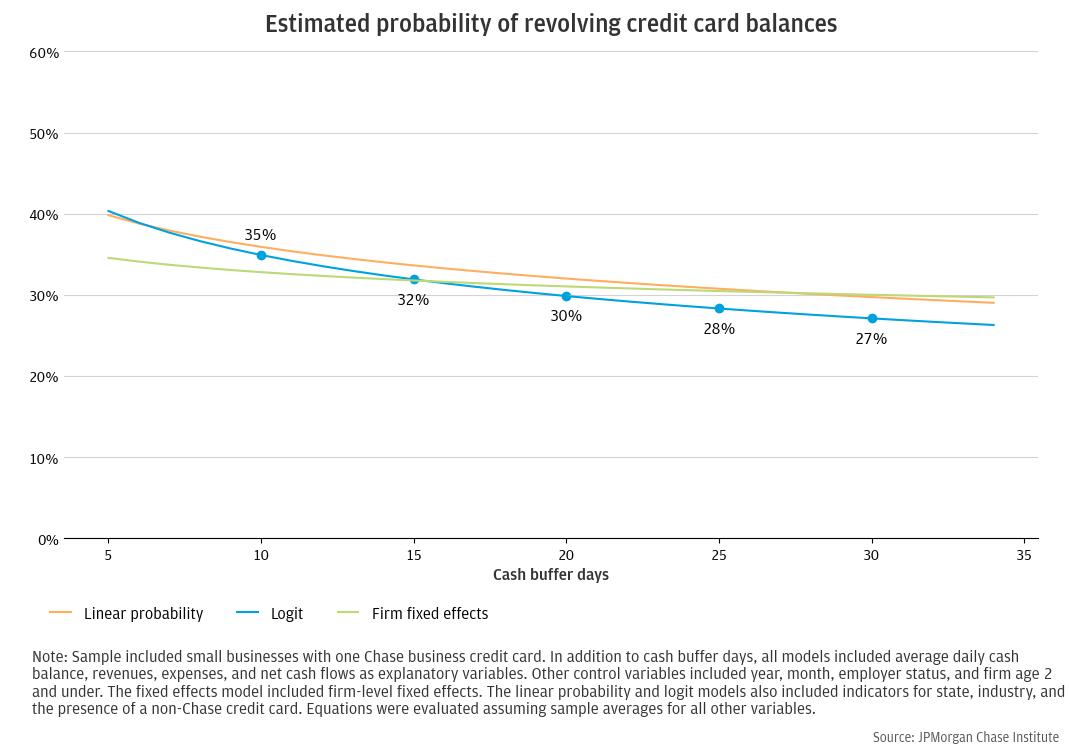

Figure 8: Estimated probability of revolving decreases as cash buffer days increase

Figure 8 shows the estimated probabilities of revolving at different levels of cash buffer days, while keeping other variables constant. The linear probability and logit models had similar slopes and estimated probabilities. For example, for firms with 10 cash buffer days, both models estimated the probability of revolving at about 35 to 36 percent. As cash buffer days increased, the probability of revolving decreased: for 20 cash buffer days, the models estimated the probability at 30 to 32 percent. This is consistent with the interpretation that firms with less cash liquidity are more likely to revolve, using their credit cards as debt financing instruments. Analogously, the estimated probability of revolving decreases as the average daily cash balance increases, and these estimates are shown in the appendix.

Also shown in Figure 8 are the estimated probabilities using a firm fixed effects model, in which firm-level constants capture firm-specific characteristics. In this type of model, firm choices—revolving a credit card balance or not—are estimated relative to the same firm. That is, the estimation considers when firm A revolved its credit card balance compared to months in which it did not. The advantage of this type of model is that it can control for unobserved heterogeneity among firms. Firm A and firm B may have similar observable characteristics, yet firm A may have a propensity to revolve while firm B does not. The disadvantage of this type of model is that any time-invariant firm characteristics drop out, and we cannot estimate coefficients for them. For example, industry does not vary over time for a given firm, so we cannot estimate the effect of industry on the probability of revolving.

The slope of the firm fixed effects model was flatter than those of the linear probability and logit models. That is, a within-firm decision to revolve is not as sensitive to changes in cash balances or cash buffer days. This is consistent with Finding 2, where we noted that the majority of firms were regularly transactors or revolvers. In contrast, the linear probability and logit models compared behavior across firms while controlling for observable firm characteristics. However, not all firm characteristics—such as the propensity to revolve—can be observed.

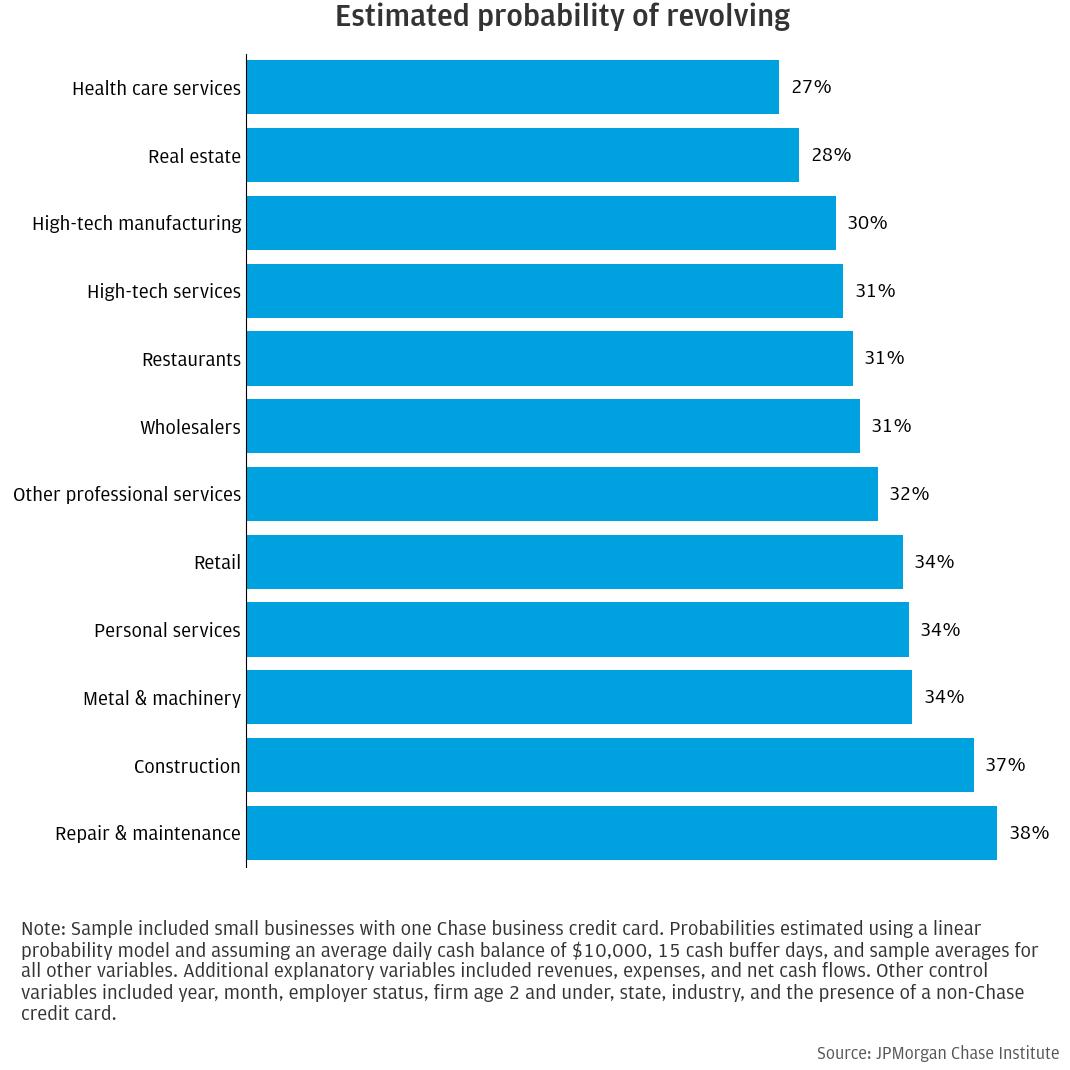

As Figure 5 showed, the share of firms revolving varied by industry: the difference between the industry with the lowest share revolving and the industry with the highest share was about 19 percentage points in 2022. Some of that variation was due to different cash liquidity and cash flows typical in each industry. Our regression models allow us to estimate the probability of revolving for each industry while holding the other variables constant across industries.

Figure 9: Differences in cash liquidity do not explain all industry variation in probability of revolving

Figure 9 shows the estimated probabilities by industry assuming average daily cash balances of $10,000 and 15 cash buffer days. These estimates remove variation in the probability of revolving that would be due to, for example, the typical cash balances in one industry being lower than the usual balances in another industry. By assuming the same values for variables other than industry, the range in probabilities decreases, and the difference between the lowest and highest probabilities is 11 percentage points. However, our models likely do not capture all the variables that differentiate the various industries.

Cash liquidity, as measured by cash buffer days and average daily cash balances, is a significant factor in the decision to revolve: firms with more cash liquidity are less likely to revolve. For these firms, credit card financing can be an alternative to cash liquidity.

In the consumer finance literature, researchers have analyzed the “credit card debt puzzle,” in which households who have liquid assets nevertheless carry balances on their credit cards. Since cash balances typically earn lower interest rates than those charged by credit cards, consumers could save money by paying down their credit card debt.

However, this behavior is not necessarily irrational. Households may want to keep some cash reserves for anticipated expenses that cannot be paid with a credit card (Telyukova 2013), or funds may already be earmarked for such future expenses. Other explanations include strategic preparation for bankruptcy (Lehnert and Maki 2002) and perceptions of future credit access risk (Gorbachev and Luengo-Prado 2019).

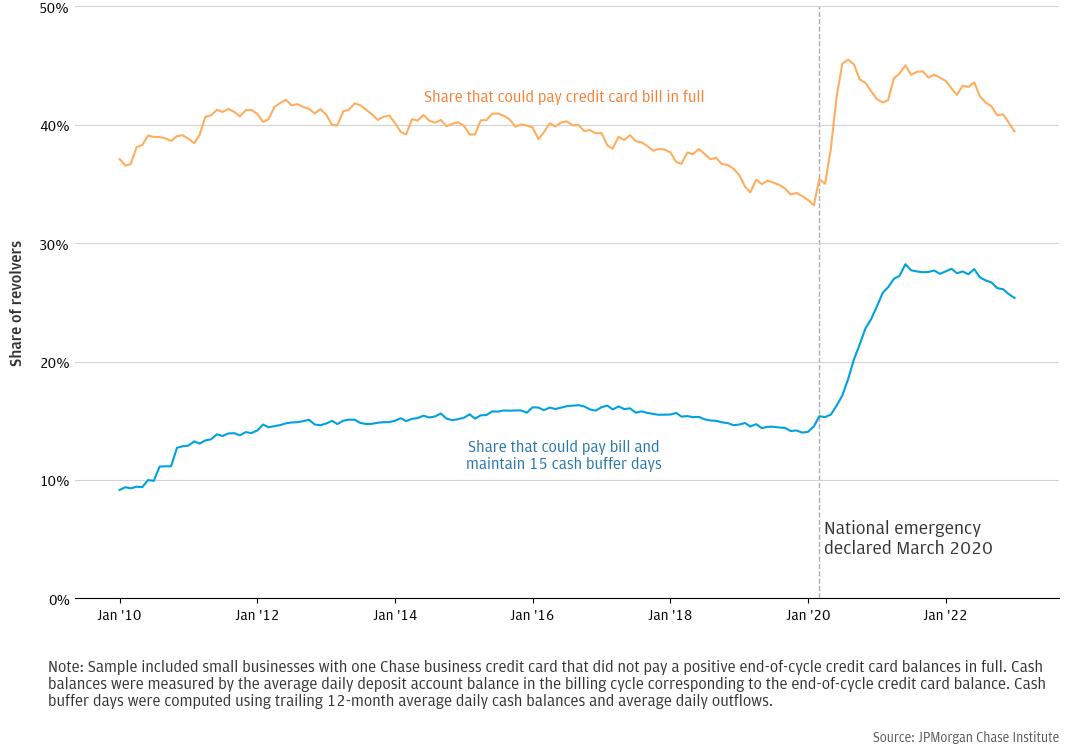

Figure 10: Some revolvers appear to have sufficient cash to pay in full

Among small businesses, we see a similar pattern in which some firms appear to have enough cash to pay their credit card balances in full but nevertheless revolve. Figure 10 shows that among those that revolved their credit card balances, about 40 percent of them had average daily cash balances14 that month to pay their end-of-cycle credit card balance in full. This share was similar to the 40.5 percent of households exhibiting this behavior15 (Gorbachev and Luengo-Prado 2019). The card holder need not pay the bill immediately, so the past month’s average daily balance may not represent the actual amount available when the firm does pay the bill. Moreover, firms could be motivated by the same reasons households are in keeping liquid assets while revolving credit card debt. Nevertheless, it does suggest that a sizable share of revolvers could have paid their credit cards in full.

Firms may want to maintain a cash buffer as a precaution for future cash expenditures. Cash buffer days measure the number of days a firm could maintain its usual outflows using its cash balance in the event of a total disruption to inflows. Prior research showed a median of 15 cash buffer days (JPMorgan Chase Institute 2020). Figure 10 also shows our estimate of the share of revolvers with sufficient cash not only to pay their credit cards in full but also to maintain 15 cash buffer days. We assumed 15 cash buffer days as an illustrative example; individual firms may prefer to maintain different levels of cash. Before 2020, about 15 percent of revolvers could have paid their credit card bills in full and maintained 15 cash buffer days.

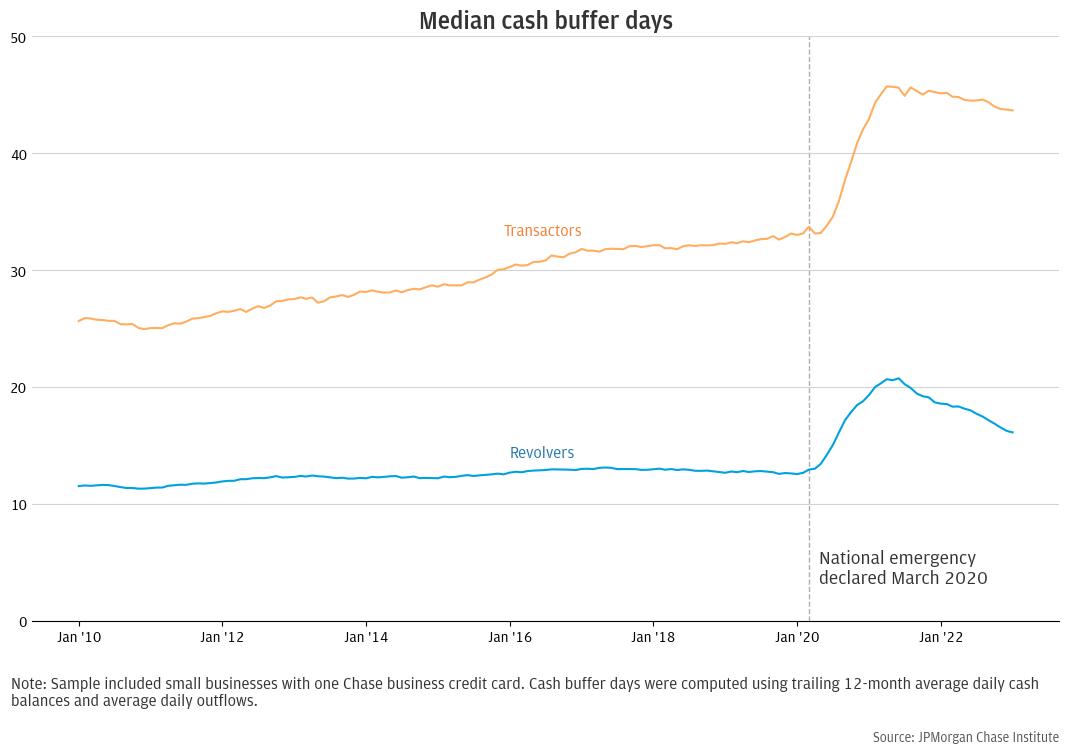

Figure 11: Transactors had twice the cash buffer days as revolvers

Cash buffers can be important factors in small business financial health. Figure 11 shows that the median number of cash buffer days among revolvers was materially lower than that of transactors. In our sample of firms with one business credit card, revolvers had a median of 11 to 13 cash buffer days before 2020. This increased to 20 in 2021 and remained higher in 2022 than pre-2020 trends. Transactors held about twice as many cash buffer days, about 33 in early 2020 and increasing to over 45 in 2021.

Figure 12: Firms with more than 15 cash buffer days were less likely to revolve and revolved lower credit card balances

Figure 12 shows the share of firms that revolved their credit card balances, based on the number of cash buffer days. Among firms with more than 15 cash buffer days, approximately 22 percent revolved their credit card balances in recent years, and the share decreased slightly after 2020. In comparison, about 50 percent of firms with 15 or fewer cash buffer days carried credit card balances in early 2020, a share that declined during the pandemic. For those that did revolve, median revolving balances were lower among firms with more than 15 cash buffer days. These relationships are consistent with our regression analysis in Finding 3. Firms with more cash liquidity are less likely to revolve.

The household credit card puzzle—where revolvers have liquid assets available to pay down their credit card balances—may have an analog among small businesses. However, if firms are motivated by maintaining a cash buffer, the incidence of this behavior would be materially reduced. This also suggests that liquidity through a credit facility is not a complete substitute for cash liquidity. Firms recognize that they may need both.

All small businesses need to manage their cash flows, which can be irregular due to unexpectedly high expenses or lower than expected revenues. In prior research we have emphasized the importance of cash buffers, which can provide liquidity in times of distress. Another source of liquidity is credit, and many small businesses have a credit card which could be used for financing. In this report, we documented how small businesses with one business credit card used their cards as means of payment as well as financing. As policymakers and decision makers consider the role of different types of credit in small business financial health, we offer the following implications of our findings:

Credit cards are part of a suite of cash flow management tools.

Credit cards can be an alternative for cash liquidity, providing financing when firms cannot pay in cash. The converse became evident after the onset of the pandemic: as deposit balances increased, fewer small businesses carried balances on their credit cards. That is, these firms reduced their borrowing when they had cash available.

Cash buffers are still important, and credit cards do not displace the role of cash.

While credit cards can provide some financing when cash reserves are insufficient, credit cards are not always accepted for the expenses small businesses face. Maintaining adequate cash buffers remains important for small business financial health. A sizable share of firms that revolve credit card balances also have sufficient cash to pay down their revolving balances, suggesting that some firms recognize the need to maintain cash reserves even when they have access to credit.

Small businesses have varied cash flow management needs which require a range of solutions.

Small business needs may range from short-term cash flow smoothing to medium- and long-term facilities that can help them expand. Cash reserves and credit cards are better suited to address short-term liquidity needs. Firms may also be able to use the credit card grace period for interest-free financing. Longer-term financing options could include lines of credit, working capital loans, supplier/vendor financing, and term loans.

Lines of credit and working capital loans may be more suitable for the sizable share of small businesses that are consistently revolving credit card balances for a year or more. The relatively low utilization of SBA lines of credit suggests that more small businesses could benefit from such products.

Our research sample includes de-identified firms with Chase Business Banking deposit accounts and one Chase business credit card linked through the owner(s) of the deposit accounts. This restriction makes the link between the small business finances and the credit card clearer, but it may not capture the complexity of how small businesses use credit cards to manage their finances. The details and implications are discussed in this section.

First, we do not consider any Chase personal credit cards the business owner may have. Business owners in our sample may also have a Chase personal card in addition to a Chase business card, but data from the personal card is not included. A firm with only a Chase personal card would be excluded from this sample. As noted earlier, a sizable share of firms, particularly those on the smaller side, use personal cards for business purposes. However, we have no method of identifying whether a business owner’s personal card is being used for her business or personal purchases. Although we may be excluding the relevant business activity from personal cards, we prefer that over the alternative of including personal card activity that is not related to the firm.

Second, we exclude firms with more than one Chase business credit card at a given time. Credit cards have billing cycles that end on different days of the month. Correlations between cash flow patterns in deposit accounts and credit card activity are clearer when there is only one card. Moreover, with multiple cards, the possibility that not all the cards are associated with the business deposit account increases.16

Third, we can only consider the use of non-Chase cards in a limited way. While we can observe what appear to be payments from the deposit account to another issuer’s credit card, we cannot discern whether those amounts represent payments in full or payments on a revolving balance. However, we do control for other credit card use by including indicator variables in our regression models. In interpreting our findings, readers should understand that we do not capture all credit card financing activity. Firms that are transactors on their Chase card may nevertheless be revolvers on another card.

Table A1: Sample characteristics, by industry

The resulting sample includes over one million small businesses between January 2010 and January 2023, with observations based on the billing cycle month (see Figure 1). Not all firms are present in the sample in every month. In any given month, about 150,000 to 440,000 firms are included, with larger sample sizes in the later years. Table A1 shows the industry distribution of the sample at the end of our analysis; the industry shares are relatively consistent over the sample period. Also shown are the median annual revenues by industry.

We estimated the probability of revolving a credit card balance using three models. The outcome variable was equal to one in months when the firm revolves its credit card balance and zero otherwise. Financial explanatory variables included average daily cash balances, cash buffer days, revenues, expenses, and net cash flows; each was transformed using the inverse hyperbolic sine (asinh) or the natural log (ln) function.

The first two models, a linear probability model and a logit model, also included firm characteristics such as industry, state, and the presence of a non-Chase credit card. The firm fixed effects model is a linear probability model with individual firm-level constants, which capture firm-specific characteristics. In this type of model, firm choices—revolving a credit card balance or not—are estimated within a firm. That is, the estimation considers when firm A revolved its credit card balance compared to months in which it did not. The advantage of this type of model is that it can control for unobserved heterogeneity among firms.

Table A2: Regression models of probability of revolving a credit card balance

Table A2 shows the estimated coefficients for the financial variables of each of these models. The variables of interest are generally statistically significant and showing the expected sign. However, the magnitudes of the effects are relatively small, with cash buffer days and the average daily cash balance having the largest coefficients across models.

Figure A1: Estimated probability of revolving decreases as cash balances increase

Based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 Statistics of U.S. Businesses and 2018 Nonemployer Statistics.

Based on data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Call Reports. Small business loans are comprised of commercial real estate loans and commercial and industrial loans (U.S. Small Business Administration 2020).

Business and personal credit cards share similar features. However, some laws and regulations may differ. For example, the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009 applies to personal but not business cards. Nevertheless, many issuers provide disclosures for business credit cards that are similar to those for consumer cards (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2010).

They must have at least 10 transactions and $500 in outflows for three months in at least one 12-month period. They have at most two deposit accounts at a given time and operate in one of the 12 industries that are characteristic of the small business sector: construction, health care services, metals and machinery manufacturing, real estate, repair and maintenance, restaurants, retail, personal services, other professional services, wholesalers, high-tech manufacturing, and high-tech services.

For consumer credit plans, grace periods are not required but if they apply, they must be at least 21 days after the statement end (Regulation Z, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/rules-policy/regulations/1026/5/#b-2-ii-A-2). While Regulation Z does not apply to small business credit cards, some issuers have elected to comply voluntarily with similar restrictions (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2010). We do not observe whether cards in our sample have grace periods.

Grace periods do not typically apply to cash advances (CFPB, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-a-grace-period-for-a-credit-card-en-47/).

The Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research announced the end of the 2007-2009 recession on September 20, 2010 (https://www.nber.org/news/business-cycle-dating-committee-announcement-september-20-2010).

The Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared a public health emergency on January 31, 2020. The President declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020 (https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2020-05794).

EIP were made to eligible individuals as opposed to firms. However, the majority of small businesses are nonemployer firms. Pass-through entities, such as sole proprietorships, report net income on their owners’ tax returns. If those tax returns used the business’s direct deposit information, the payments could have been deposited into the business checking accounts.

Net cash flow is defined as inflows less outflows and is not the same as revenues less expenses. We estimate revenues (expenses) as inflows (outflows) excluding financing flows. Financing inflows include non-revenue items like loan inflows and transfers from other accounts. Financial outflows include non-expenses such as transfers to other accounts. Credit card payments are considered financial outflows in this model, which may not seem obvious. For firms that pay their credit card bills in full each month and do not incur interest charges, credit card payments are nevertheless the repayment of short-term loans (during the grace period). Loan payments, which include both principal and interest components, would be considered financing flows.

Cash buffer days were transformed using the natural logarithm. The remaining financial variables were transformed using the inverse hyperbolic sine function, denoted as asinh, which has similar properties as the natural logarithm but is defined at zero. This transformation helps with the skewness in these variables.

Cash buffer days for a given month was calculated using the average daily cash balance and average daily outflows for the trailing 12-month period. This longer period was chosen to mitigate variations in cash buffer days due to short-term changes in balances and outflows.

If measured with shorter periods, cash buffer days can fluctuate in idiosyncratic ways. For example, consider a firm with a month of low outflows and no change in cash balances. If cash buffer days were calculated based on one month, then it would increase materially even though this hypothetical firm likely did not have more cash liquidity than in a previous month.

We used the average daily cash balance for that month instead of the cash balance on the last day of the billing cycle because it should be less exposed to the idiosyncratic noise around the billing date. For example, firms may have coincidentally large inflows or outflows just before the credit card billing cycle ended, and measuring the cash balance at one day may be misleading.

Using data from 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances (Gorbachev and Luengo-Prado 2019).

In our sample, it is also possible that the one Chase business card is not being used for purposes related to the business with the Chase business deposit account. However, we believe it is a reasonable assumption that the business deposit account and business credit card belonging to the same owners are linked.

Blanchflower, David and David S. Evans. 2004. “The role of credit cards in providing financing for small businesses.” The Payment Card Economics Review 2, Winter.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2010. “Report to the Congress on the Use of Credit Cards by Small Businesses and the Credit Card Market for Small Businesses.” https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/conferences/sbc_smallbusinesscredit.pdf.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. 2019. “Data Point: Credit Card Revolvers.” https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/data-point-credit-card-revolvers/.

Dilger, Robert Jay and Anthony A. Cilluffo. 2022. “Small Business Administration 7(a) Loan Guaranty Program.” Congressional Research Service report R41146. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41146.

Farrell, Diana, Christopher Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2018. “Growth, Vitality, and Cash Flows: High-Frequency Evidence from 1 Million Small Businesses.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/report-growth-vitality-cash-flows.htm.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2020a. “Small Business Financial Outcomes during the Onset of COVID-19.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/small-business-financial-outcomes-during-the-onset-of-covid-19.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2020b. “Small Business Financial Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/report-small-business-financial-outcomes-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2020c. “A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/a-cash-flow-perspective-on-the-small-business-sector.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, Chi Mac, and Bryan Kim. 2020. “Small Business Expenses during COVID-19.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/report-small-business-expenses-during-COVID-19.

Federal Reserve. 2018. “Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Nonemployer Firms.” https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/-/media/project/smallbizcredittenant/fedsmallbusinesssite/fedsmallbusiness/files/2018/sbcs-nonemployer-firms-report.pdf.

Federal Reserve. 2019. “Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Employer Firms.” https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/-/media/project/smallbizcredittenant/fedsmallbusinesssite/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/sbcs-employer-firms-report.pdf.

Gorbachev, Olga and Maria Jose Luengo-Prado. 2019. “The Credit Card Debt Puzzle: The Role of Preferences, Credit Access Risk, and Financial Literacy.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 101, no. 2: 1-16.

Herbst-Murphy, Susan. 2012. “Small Business Use of Credit Cards in the U.S. Market.” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Payment Cards Center Discussion Paper. https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/frbp/assets/consumer-finance/discussion-papers/d-2012-small-business-use-of-credit-cards.pdf.

JPMorgan Chase Institute. 2020. “Small Business Cash Liquidity in 25 Metro Areas.” https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/small-business-cash-liquidity-in-25-metro-areas.

Lehnert, Andreas and Dean M. Maki. 2002. “Consumption, Debt and Portfolio Choice: Testing the Effect of Bankruptcy Law.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Finance and Economics Discussion Series. https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2002/200214/200214pap.pdf.

National Federation of Independent Business. 2012. “Small Business, Credit Access, and a Lingering Recession.”

Telyukova, Irina A. 2013. “Household Need for Liquidity and the Credit Card Debt Puzzle.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 80, no. 3: 1148-1177.

U.S. Small Business Administration. 2020. “Small Business Lending in the United States, 2019.” https://advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Report-2019-Small-Business-Lending-Report.pdf.

We thank Noah Forougi, Karmen Hutchinson, and Man Xu for their hard work and vital contributions to this research. Additionally, we thank Annabel Jouard and Alfonso Zenteno for their support. We are indebted to our internal partners and colleagues, who support delivery of our agenda in a myriad of ways and acknowledge their contributions to each and all releases.

We would like to acknowledge Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., for his vision and leadership in establishing the Institute and enabling the ongoing research agenda. We remain deeply grateful to Demetrios Marantis, Head of Corporate Responsibility, Heather Higginbottom, Head of Research & Policy, and others across the firm for the resources and support to pioneer a new approach to contribute to global economic analysis and insight.

This material is a product of JPMorgan Chase Institute and is provided to you solely for general information purposes. Unless otherwise specifically stated, any views or opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors listed and may differ from the views and opinions expressed by J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS) Research Department or other departments or divisions of JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates. This material is not a product of the Research Department of JPMS. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively J.P. Morgan) do not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. No representation or warranty should be made with regard to any computations, graphs, tables, diagrams or commentary in this material, which is provided for illustration/reference purposes only. The data relied on for this report are based on past transactions and may not be indicative of future results. J.P. Morgan assumes no duty to update any information in this material in the event that such information changes. The opinion herein should not be construed as an individual recommendation for any particular client and is not intended as advice or recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, or strategies for a particular client. This material does not constitute a solicitation or offer in any jurisdiction where such a solicitation is unlawful.

Wheat, Chris, and Chi Mac. 2023. “Cash or credit: small business use of credit cards for cash flow management.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/insights/business-growth-and-entrepreneurship/small-business-use-of-credit-cards

Authors

Chris Wheat

President, JPMorganChase Institute

Chi Mac

Business Research Director